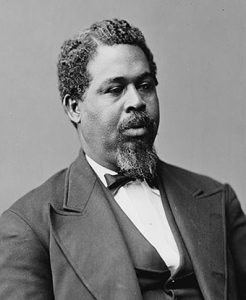

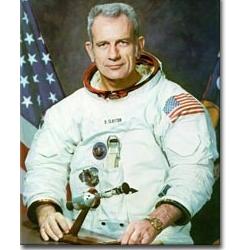

Deke Slayton

One of the original seven astronauts selected for NASA’s Mercury program, Donald K. “Deke” Slayton was grounded due to a medical condition before he could fly a mission and became the “chief astronaut” responsible for assigning crews for the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs. Though not necessarily the first person most people think of when they talk about astronauts, he played an important role in NASA’s early history, including choosing the Apollo 11 crew for the first lunar landing.

One of the original seven astronauts selected for NASA’s Mercury program, Donald K. “Deke” Slayton was grounded due to a medical condition before he could fly a mission and became the “chief astronaut” responsible for assigning crews for the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs. Though not necessarily the first person most people think of when they talk about astronauts, he played an important role in NASA’s early history, including choosing the Apollo 11 crew for the first lunar landing.Wisconsin Farm Boy

Deke Slayton’s family owned a farm only a mile north of Leon, Wisconsin. His relatives all called him “Don.” He wouldn’t pick up the nickname of “Deke” until he was an adult in the Air Force. His mother used to worry about him running across the road even though there wasn’t much traffic. Not that there was much to run to; the only town in the area of any significant size was Sparta and that only had 5,280 people. As he got older, he became more and more involved in farm chores and his mother worried less about him running off.

At five years old, he had an accident that would make him self-conscious until he was in his twenties. His family had a horse-drawn hay mower with a sickle bar that would occasionally get clogged with hay. When that happened, the driver would back the horses up a step and then clean the sickle bar off. Deke Slayton was following along behind the mower when this happened. He wanted to help, so he stuck his finger in the sickle bar to try to clean it out. His father backed up the horses a step and the sickle bar snipped his ring finger clean off. It didn’t hurt much, but his father ran him to the nearest hospital, where he had anesthesia for the first time in his life. Other than being self-conscious about it, the missing finger didn’t affect him much until he went to enter the Army Air Force. They had to look up a regulation on missing fingers. It was okay to lose the ring finger on the left hand if a candidate was right-handed, as Slayton was.

Grade school was a two-room building that Slayton would walk or ski to, depending on which season it was. He did well and was well-liked by the teachers. His only problem was speaking in front of the class. He would get stage fright and freeze. He didn’t get into much mischief, remembering only one time when he threw a snowball into a classroom. He was so ashamed of himself that he confessed.

High school was in Sparta, five miles away, and he could ride the school bus or ride his bicycle to school. He took up boxing and would often ride in a Model-T to and from school with other boxers. World War II started and he acquired an interest in planes from watching all the army airplanes flying around from Camp McCoy. So during his junior year, he dropped all his agriculture classes and signed up for physics, chemistry and math. His father was disappointed that he wouldn’t take over the farm, but he had a brother named Howard who stayed in agriculture. The U.S. joined the war during his senior year and, when he graduated, he joined the Army Air Force.

Army Air Force

At the time, the Air Force wasn’t a separate branch of the military. It was part of the Army. In true Army fashion, they asked Slayton whether he wanted to fly single-engine or multi-engine planes. He told them single-engine planes, and they assigned him to multi-engine planes. He tried to protest the orders along with a friend for whom it was the other way around, but didn’t get very far.

Basic training went quite well for him. Within ten hours, he had mastered the basics of flying and even helped an instructor who also hunted flush out ducks in his airplane. This was risky; he would have ducks flying all around his plane and he could have easily hit one. Those things could tear up an engine. When he finished advanced training, he was assigned his last choice for airplane models: a B-25 bomber.

While training in the B-25, he witnessed his first mid-air casualty. He and some other pilots had just flown through some clouds and the planes were spread out pretty far apart. So they tried to join up in formation and a plane on the lead planes left wing collided with the lead’s tail, taking it clean off. The lead plane’s crew had no chance to bail out before they hit the ground. Slayton learned from that not to worry too much about getting killed, because death could sneak up on a person anywhere.

He survived aerial bombings three times before he even reached his unit, once while still on a Navy ship and twice in Naples. At nineteen, he was one of the youngest in the 340th Bombardment Group stationed just outside San Petrazio. He was terrified during his first mission, but it turned out to be an easy bombing run. He kept wondering when the German flak was going to fly and saw none. After that, it got much worse. The Germans would let the anti-aircraft flak fly for a while, and then send in their airplanes. A few times, Slayton saw Junkers that had a nasty habit of attacking from above. The bombing line didn’t move much during the winter of 1943-44. Slayton’s group didn’t doubt that they would win the war, but they learned to respect German resilience.

Post-World War II

After the end of the war, Deke Slayton returned to the U.S., taking along a little white dog a buddy of his had adopted. His friend never returned to claim the dog, so he left it at the Slayton farm. He was going to try for his commission; in the meantime, the Army assigned him to Boca Raton, where he doubled as a flying instructor and assistant information and education officer. His main “success” in Boca Raton was spreading some propaganda pamphlets from the Russian Embassy. His predecessor had somehow managed to get on their mailing list. Slayton got called out for it and was fortunately able to convince his superiors that he was a slightly stupid innocent bystander in the whole thing.

He also bought his first car, a Packard Super 8 that turned out to be a lemon. He had to put up with a radiator with a habit of overheating, blown out tires, and the occasional misadventure with his friends, and finally sold it on consignment. He paid $800 for it and got $500. After that, he was more careful when it came to choosing cars.

Slayton began to notice a pattern with his colleagues who managed to get commissions. They all had college degrees. In November 1946, he put his military career on hold and applied to the University of Minnesota for their aeronautical engineering program. He made it on the GI Bill, got some credit for his military service and took a full load. To make some extra cash, he got a job at Montgomery Ward, unloading freight cars. He also flew with the Air Force Reserve and then the Air National Guard. The only plane he took a dislike to in the Guard was a C-47 transport, the “Gooney Bird,” used to fly high-ranking state officials like the governor to their destinations. Of course, he always ended up being the one to fly it whenever the governor needed to go somewhere.

He graduated with a bachelor’s degree after two and a half years at Minnesota and was promptly hired by Boeing. He was off to Seattle, where the only people he initially knew were two other Minnesota graduates. He found the mountains perfect for skiing, though he almost wiped out on his first run. Boeing put him in the change group, which had to draft changes made to their airplane designs, and then moved him over to structural design work on the B-52 bomber. Then, the Korean War broke out and he dumped his job at Boeing to rejoin the Air Guard, which made him a maintenance officer.

He also did the test flights for the planes he worked on. One day, he was flying over the Mississippi River when he saw a white object that looked like a kite. He quickly decided that nobody was going to fly a kite at ten thousand feet and kept an eye on it. Then, it took on the shape of a weather balloon. Just for fun, he made a pass on it, and it suddenly looked eerily like a disk on edge! The object began a 45-degree climb. Slayton tried to follow, but couldn’t keep up and it vanished. He later learned that somebody on the ground had seen the object, too, and tracked it at four thousand miles per hour. He wasn’t one to jump to conclusions and accepted the official story that it was somebody’s weather balloon.

He rejoined the Air Force in 1952, got the commission he wanted, and ended up in Germany doing inspection tours. He protested; he was the only person he knew who actually wanted to go to Korea. It did him no good and he chalked it up to a “typical military decision.” Desperate to get out, he filed an application for a post at Edwards Air Force Base, but that fell through. Finally, he met up with a sympathetic colonel who was able to get him a slot with an F-86 unit.

On the plus side, he met his future wife, a secretary named Marge. They married in May of 1955, just before he left Germany to go to test pilot school.

Edwards Air Force Base

Edwards Air Force Base was where new fighter planes were developed and tested for the Air Force. NASA’s predecessor, called NACA, also had facilities there for high-speed research. This was where Yeager had first broken the sound barrier and they were also working on Mach 2 and Mach 3 planes. Being a test pilot was risky, a situation made worse by poor flight test instrumentation.

Edwards Air Force Base was where new fighter planes were developed and tested for the Air Force. NASA’s predecessor, called NACA, also had facilities there for high-speed research. This was where Yeager had first broken the sound barrier and they were also working on Mach 2 and Mach 3 planes. Being a test pilot was risky, a situation made worse by poor flight test instrumentation.

Deke Slayton graduated from test pilot school in December of 1955 and arrived at Edwards shortly after. This is where he picked up the nickname of “Deke.” There was another test pilot there by the name of Don Sorlie, so they started calling Donald K. Slayton “D.K.,” which eventually became “Deke.”

He disliked the base commander, who rapidly gained a reputation for being a prude and would insist on flying planes he wasn’t really qualified for. One time, the commander was trying out the new F-107 and Slayton was flying along on chase duty, when the F-107 just disappeared. A glitch in the plane’s avionics system had shot him right up into the air. The commander wasn’t too happy but Slayton got a laugh out of it. The commander was eventually replaced by Marcus Cooper, whom Slayton thought was less of a jerk.

He was still at Edwards when the Russians launched Sputnik. While walking his dog on a clear night, he tried spotting it but missed. His dog was barking at something in the desert, so he finally gave up and went back inside. But the Space Race was on and would soon change things for a lot of Americans, including him. He received sealed orders to report to Washington, D.C. in January of 1959.

NASA

With Sputnik, the American space program began getting into high gear. NACA was dissolved and was replaced by NASA, which inherited most of its resources. After a few rocket mishaps, German engineer Wernher von Braun was called in with his Jupiter-C rocket. It successfully launched Explorer 1 into orbit and would evolve into the Redstone and Atlas rockets used for the manned Mercury missions.

With Sputnik, the American space program began getting into high gear. NACA was dissolved and was replaced by NASA, which inherited most of its resources. After a few rocket mishaps, German engineer Wernher von Braun was called in with his Jupiter-C rocket. It successfully launched Explorer 1 into orbit and would evolve into the Redstone and Atlas rockets used for the manned Mercury missions.

Deke Slayton was one of 110 astronaut candidates from the Air Force, Navy and Marines, separated into three roughly equal groups. That number was quickly whittled down to 69. NASA wanted courageous and intelligent men, preferably test pilots with college degrees, and looked at quite a few people at Edwards. Some people were more enthusiastic than others, especially after they heard that it could mean suspending their military careers and maybe even giving up flying airplanes. Slayton was one of the enthusiastic ones.

They went to Lovelace Clinic in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for the extensive medical tests. Base Commander Cooper advised Slayton and the other candidates who worked at Edwards to stay out of it, thinking that the Mercury program wasn’t worth suspending an Air Force career for. Slayton didn’t listen, mostly because he was almost due to be transferred out of Edwards anyway. Edwards was where things were happening in the world of airplane development and a test pilot could only go downhill from there. He was grouped with five other guys, which included a Navy man named Scott Carpenter. Anybody who hated doctors probably would have backed out at this point, and a few did. Slayton thought he did pretty well and went on to Dayton, Ohio for the psychological tests. He thought most of those were pretty pointless, though he did catch a nap when they put him in a blackout chamber.

Finally, he got back to Edwards to wait and do paperwork. Then, he got a call from Charlie Donlan: “You’ve been selected to join us, if you’re still interested.”

“Yes sir, I am.”

Introduction of the Astronauts

The press packed into the ballroom of the Dolly Madison House while seven new recruits were fussed over by NASA brass. They jockeyed for places for their cameras and microphones while they waited for the introduction of the astronauts. The Mercury Seven did not necessarily see what all the excitement was about. They were used to pushing the boundaries, testing the limits of new airplanes, and the space program represented a new frontier for them. Slayton was especially anxious about facing the reporters, remembering his old fear of public speaking.

He took his place beside Alan Shepard, a Navy pilot he knew mostly by reputation. Shepard noticed Slayton’s nervousness and couldn’t resist needling him about his bow tie. “I doubt if the cameras will pick up that smeared egg or catsup or whatever that guck is on it.” That did nothing for Slayton’s confidence and he kept trying to subtly see what was on his tie. As they took their seats, NASA personnel worked their way through the reporters, handing out press releases. Then, the reporters were unleashed to take their pictures.

“These people are nuts!” Shepard declared, echoing most of the new astronauts’ thoughts. Of course, Slayton was still worrying about his tie. One reporter managed to crawl his way through the crowd and aim his camera straight at Slayton. “Hey, Slayton! Look over here, willya? Yeah, look right this way! Smile!”

“I’m smiling,” Slayton grunted through clenched teeth. “All of God’s children are smiling.”

“God, that tie,” Shepard muttered to him.

A NASA official called the reporters to order. The crowd wiggled backward. Slayton compared it to a worm farm. Finally, Shepard broke down and admitted, “There’s nothing on your tie, Slayton.”

“What?”

“Gotcha!”

“Gotcha? What?” Then, Slayton realized he had been had. “Shepard, you-”

So America was introduced to its first astronauts and Slayton was introduced to the infamous “Gotcha!” on the same day.

Dealing with the Reporters

Slayton’s whole family suddenly found themselves having to dodge reporters and photographers. His toddler son thought the microphones would make great toys, and Marge Slayton did her best to give honest answers to the flood of questions. She explained that, while she was somewhat apprehensive about the risks of her husband’s new job, it was no worse than the risks of being an ordinary test pilot at Edwards. Slayton had certainly had his share of close calls, including one F-105 that had spun out of control. The telephone rang and she answered it, and the next day, there was a picture of her on the phone with her husband on the front page of newspapers across the country.

Clearly, something needed to be done to protect the astronauts’ private lives. Slayton certainly didn’t think he or any of the other astronauts had done anything to deserve such celebrity. A lawyer by the name of Leo D’Orsey offered to represent the astronauts and worked out an exclusive deal with Life magazine, which would both protect the astronauts’ families from being swarmed and bring in some extra income over the next four years. They still had to deal with individual reporters wanting an interview, but in some cases, they could decline on the grounds of an exclusive contract.

A Whole New Life

Deke Slayton moved to Stoneybrook, Virginia, where Gus Grissom became his next door neighbor and Wally Schirra lived right down the street. They often carpooled on the way to Langley Air Force Base, where the NASA center was then located. At first, other test pilots thought the whole Mercury thing was a joke and made wisecracks about the astronauts being put on the same level as the chimpanzees NASA flew on some test flights. Slayton got fed up with it and addressed the jokes in a paper he wrote for a meeting of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots: “To send anyone of lesser technical ability would be equivalent to sending a pilot to perform a complex exploratory medical operation. Assuming he didn’t kill the patient, he wouldn’t know what had happened when it was over.”

Deke Slayton moved to Stoneybrook, Virginia, where Gus Grissom became his next door neighbor and Wally Schirra lived right down the street. They often carpooled on the way to Langley Air Force Base, where the NASA center was then located. At first, other test pilots thought the whole Mercury thing was a joke and made wisecracks about the astronauts being put on the same level as the chimpanzees NASA flew on some test flights. Slayton got fed up with it and addressed the jokes in a paper he wrote for a meeting of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots: “To send anyone of lesser technical ability would be equivalent to sending a pilot to perform a complex exploratory medical operation. Assuming he didn’t kill the patient, he wouldn’t know what had happened when it was over.”

They jumped into training right away. NASA staff was still refining the training process. They didn’t have actual space flight simulators yet, and it would be some time before survival training began. They did have a limited number of centrifuges and a device called the MASTIF, which could spin on all three axes while an astronaut tried to stabilize it. The MASTIF would eventually drop out of sight. They would also be busy with PR work. Slayton’s part in the PR circuit included accepting at least one honorary degree and giving tours to members of Congress. With all this, each astronaut could easily be working all day and well into the evening.

At first, the group complained about having no airplanes. Somehow, reporters got wind of this and started yakking about low astronaut morale. It took a while to convince the media that this wasn’t the case. NASA did manage to find some T-33s for the astronauts.

Meanwhile, work continued on both the Mercury spacecraft and the rockets that would take them into space. It was frustrating work, partly because the early rockets had a bad habit of blowing up or not launching at all. After watching one Atlas explode, congressmen asked the astronauts variations of, “You’re actually going to ride one of these things?” It was a learning process for everybody involved but, by the time they started launching men, the NASA engineers thought they had most of the problems solved.

Slayton was training in the centrifuge when flight surgeon William Douglas noticed something odd about his heartbeat. At first, he dismissed at as faulty equipment. It didn’t go away, so he sent Slayton in for a checkup and it turned out that he had idiopathic atrial fibrillation. This meant his heartbeat would occasionally become irregular. Douglas didn’t think it was anything serious but wanted to check it out with other specialists. The specialists assured both Slayton and NASA that it wasn’t likely to affect his ability to fly. Still, it would affect his career as an astronaut once the wrong people got wind of it.

Grounded!

Deke Slayton was assigned to fly the second orbital mission, Mercury-Atlas 7. Unfortunately, NASA had political enemies, chief among them being Jerome Weisner. He was one of Kennedy’s advisors and had opposed the manned space program. Though Kennedy overrode him, he found a convenient place to take his frustrations out on when he heard about Slayton’s heart condition. He managed to corner NASA chief James Webb and pointed out some harsh realities. At this stage in the game, it could spell the end of NASA’s manned space program if something went wrong with Slayton’s flight and word got out about the fibrillation. Webb reluctantly agreed to look into the matter and pulled Slayton from the flight.

Slayton, naturally, was not happy about it. He fumed to NASA physician Bill Douglas, “Those sons-a-bitches can’t do this to me!” Douglas was sympathetic but there wasn’t much he could do except try to find specialists who could clear Slayton for flight. Making it worse, Wally Schirra was supposed to be Slayton’s backup, but he got passed over in favor of Scott Carpenter, who had more simulator time. It wouldn’t be long before the Air Force, in which he was still an officer, would do their best to restrict his ability to fly airplanes. This would eventually lead to him resigning from the Air Force a year before he would have been eligible for retirement. Slayton could have murdered somebody at the press conference announcing his grounding, but managed to restrain himself.

Slayton wasn’t about to give up, however, and he had a support team in the form of the other six astronauts. They held a meeting and decided to suggest that Slayton take charge of the Astronaut Office. But they would have to move fast. As Gordon Cooper put it, “There’s some hogwash about bringing in an Air Force general, or maybe an admiral. … We don’t need some outside weenie coming in here and telling us what to do.” The astronauts took a persuasive case to NASA’s senior staff and Slayton soon gained a reputation for being a take-charge individual.

Chief Astronaut

At the Astronaut Office, Slayton became responsible for crew assignments and also acted as a buffer between the rest of NASA and the astronauts. Years later, NASA nurse Dee O’Hara would comment on how he became the astronauts’ champion. Anyone who wanted to criticize the astronauts would have to go through him. He even went so far as to go to bat for Gordon Cooper, whose way of venting frustration was to rattle windows by firing his afterburner while flying over NASA’s headquarters. Slayton had to do a lot of fast talking to convince Mercury operations director Walt Williams that it was only Cooper’s way of saying good morning.

At the Astronaut Office, Slayton became responsible for crew assignments and also acted as a buffer between the rest of NASA and the astronauts. Years later, NASA nurse Dee O’Hara would comment on how he became the astronauts’ champion. Anyone who wanted to criticize the astronauts would have to go through him. He even went so far as to go to bat for Gordon Cooper, whose way of venting frustration was to rattle windows by firing his afterburner while flying over NASA’s headquarters. Slayton had to do a lot of fast talking to convince Mercury operations director Walt Williams that it was only Cooper’s way of saying good morning.

One of Slayton’s first tasks was to help choose the second group of nine astronauts, which would include Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman and James Lovell. He raised the height limit to six feet and scaled back the age limit from 40 to 35. He also accepted applications from civilians and asked for letters of recommendation from applicants’ bosses. They ended up with nine new astronauts, which Slayton referred to as the best all-around group of any astronaut group he worked with.

He still hoped for a Gemini or Apollo flight, so he did his best to keep his training current. Gemini was running into costly developmental delays in 1962 and early 1963. A planned paraglider experiment got shelved and they had trouble with a new ejection system they were trying to work out. They were finally able to slate Gemini’s first manned flight in October 1964 and the second in January 1965. They were also beginning to bat around ideas for the Apollo missions, such as what the lunar lander would look like and the route they would take to the moon. The route became quite a hot debate, with the people at the Manned Space Center favoring Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR) and the rocket design team headed by Wernher von Braun favoring Earth Orbit Rendezvous (EOR). Finally, NASA heads announced that they would go with LOR.

In the meantime, the Mercury program ended with Gordon Cooper’s successful Faith 7 on May 15-16, 1963. He brought it in for a successful manual landing when a system failure forced him to cut the mission short. It was the sixth and final Mercury flight; even if Deke Slayton hadn’t been unceremoniously yanked from his flight, one of the original seven astronauts would have been shorted.

By 1963, Slayton decided that they would need a third group of at least ten new astronauts. The Russians made the situation interesting by sending a female cosmonaut named Valentina Tereshkova into orbit in June 1963. She got space-sick but the Russians still played it for all the publicity they could get out of it. While there were woman aviators in America, Slayton didn’t think any of them were eligible to become astronauts by the standards of the 1960s. They selected fourteen astronauts, which included Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins.

In October 1963, Slayton was promoted to assistant director of Flight Crew Operations in the hopes that he could help solve some friction between the astronauts and those who should have been supporting them. This expanded his responsibilities to include the Flight Crew Support Division and the Aircraft Operations Group along with the Astronaut Office. He continued to run the Astronaut Office directly until Alan Shepard was grounded with an ear condition that caused dizziness and took charge.

Gemini

Even though Mercury was a success, America was still falling behind in the space race. The Soviet Union was the first to have two flights up at the same time, and then the first to have a successful EVA, or “space walk”. Gemini would hopefully close the gap by featuring rendezvous, docking, and EVA activity.

Even though Mercury was a success, America was still falling behind in the space race. The Soviet Union was the first to have two flights up at the same time, and then the first to have a successful EVA, or “space walk”. Gemini would hopefully close the gap by featuring rendezvous, docking, and EVA activity.

Deke Slayton was still in charge of crew selections. When it came time to start assigning crews for the Gemini missions, he worked out a three-mission rotation with a prime crew and backup crew for each. His prime crew for Gemini 3 was Alan Shepard as commander and Tom Stafford as pilot. When Alan Shepard began having debilitating dizzy spells, Slayton was forced to switch to his backup crew of Gus Grissom and John Young. They successfully tested Gemini’s new maneuvering system but the mission would forever be remembered for a smuggled corned beef sandwich and Grissom’s name of Molly Brown. It would be the last named spacecraft until they began flying the lunar module on Apollo missions.

Jim McDivitt and Ed White flew Gemini 4, which featured the first EVA by an American and some extra maneuvering tests. It was so successful that NASA decided to go for an eight-day rather than a five-day mission for Gemini 5. Gordon Cooper and Pete Conrad were assigned as the prime crew and Conrad came up with the idea for the patch. It showed a Conestoga wagon and the motto, “Eight Days or Bust.” The PR team did not like the motto very much because the mission could be seen as a failure if it didn’t go the full eight days and how it would translate into certain languages. They wound up making the full eight days and beat the record then held by the Russians. The American team was finally beginning to feel like they were catching up.

Deke Slayton attended an international space congress with Cooper and Conrad soon after Gemini 5 and got a chance to meet Russian cosmonauts Pavel Belyayev and Alexei Leonov. Over drinks, Slayton proposed a toast to the idea of sharing a drink with the Russians while in orbit. It seemed like a nice idea at the time and Slayton had no idea how prophetic his toast would prove to be.

Gemini 6 was originally supposed to dock with an unmanned Agena. However, the ground crew lost all telemetry with the Agena soon after it separated from its Atlas rocket. They believed that the Agena had probably exploded. That meant Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford had to wait while they made some decisions. NASA administrator James Webb liked the idea of having two manned spacecraft up at the same time, so they decided to have Gemini 6 rendezvous with Gemini 7, though they wouldn’t dock. This would mean another victory over the Russians, who had previously had two missions up at the same time but hadn’t been able to rendezvous. The crew for Gemini 7 would be Frank Borman and James Lovell.

Gemini 7 went into orbit as planned but Gemini 6 still had problems. When it came time for liftoff, the engines lit for a second and then shut down. Wally Schirra could have pulled the D-ring that would activate the ejection system, which would have been a risky move when they were still on the ground. He didn’t and would later comment that he could feel by the seat of his pants that they were still on the pad. They made it into orbit three days later. The rendezvous was a success, including some fun as the two crews held up signs with such jokes as, “Deke Slayton, are you a turtle?” Slayton couldn’t resist recording the usual answer, “You bet your sweet ass I am!”

Gemini 8, crewed by Neil Armstrong and David Scott, successfully docked with an Agena but they had to abort early when a malfunctioning thruster caused them to go into a tumble. Gemini 9, crewed by Tom Stafford and Gene Cernan, was to feature another Agena docking but the shroud had failed to come off. Stafford said it made the Agena look like “an angry alligator.” Gemini 10, crewed by John Young and Michael Collins, docked with two Agenas though a whifferdill cost them some fuel and they had to use the first Agena to boost them toward the second. Gemini 10 also featured two EVAs by Michael Collins. Richard Gordon and Pete Conrad flew on Gemini 11, docked with another Agena, and conducted an experiment that involved spinning the spacecraft to produce artificial gravity. James Lovell and Buzz Aldrin flew Gemini 12, in which Aldrin performed three EVAs.

While Gemini was winding down, Slayton began assigning crews for the Apollo missions. His choices for the Apollo 1 prime crew were Gus Grissom, Edward White and Roger Chaffee.

Fire!

Slayton thought of Gus Grissom as being his best friend out of the entire astronaut corps. Grissom had gotten a bad rap for losing the Liberty Bell 7 but wasn’t afraid to jump in there and get the job done. He had been so helpful while NASA was designing Gemini that they jokingly called it the “Gusmobile.” He had flown the first manned Gemini and Slayton thought nothing of giving him the first manned Apollo, too.

Slayton thought of Gus Grissom as being his best friend out of the entire astronaut corps. Grissom had gotten a bad rap for losing the Liberty Bell 7 but wasn’t afraid to jump in there and get the job done. He had been so helpful while NASA was designing Gemini that they jokingly called it the “Gusmobile.” He had flown the first manned Gemini and Slayton thought nothing of giving him the first manned Apollo, too.

Unfortunately, they had some serious problems, complacency being one of them. Another was contractor North American Aviation, which had helped with the X-15 plane but hadn’t had much to do with manned space flight. The problems mounted up so badly that Grissom hung a lemon on the flight vehicle. They should have paid attention.

The actual flight was planned for February 21st, 1967. They decided to have a dress rehearsal on January 27 and the day began with Slayton having breakfast with the crew. Then, Grissom, White and Chaffee suited up and Slayton rode with them out to the pad. Some communications problems cropped up, causing Grissom to gripe, “How can we get to the moon if we can’t talk between two buildings?” The crew also reported smelling smoke on at least two occasions. Then, Chaffee reported, “Fire in the spacecraft!”

In the 100% oxygen atmosphere, the fire raged out of control. There was no way they could get the hatch open in time. It was over in seconds. A badly shaken Slayton spent most of the rest of the day making phone calls to inform Bob Gilruth, Jim Webb, and several others, most of whom were at a dinner not far from the White House. He didn’t get much sleep that night. If Grissom hadn’t died in the fire, Slayton would have assigned him to be the first to walk on the moon.

Apollo

After the fire, there wasn’t much anyone could do but keep pressing forward. Soon after the funerals, the widows presented Slayton with gold astronaut wings that Grissom, White and Chaffee would have given him after their flight. Slayton wore it ever since, except for one week when Neil Armstrong carried them to the moon and back. The accident led to an exhaustive investigation and several changes to the Apollo spacecraft.

After the fire, there wasn’t much anyone could do but keep pressing forward. Soon after the funerals, the widows presented Slayton with gold astronaut wings that Grissom, White and Chaffee would have given him after their flight. Slayton wore it ever since, except for one week when Neil Armstrong carried them to the moon and back. The accident led to an exhaustive investigation and several changes to the Apollo spacecraft.

Slayton had to shuffle his crews due to the fire, a few accidents involving airplanes, and a retirement. The next few launches were unmanned tests and they finally got back into action again with Apollo 7. It successfully shook down the Command and Service Module and would be Wally Schirra’s last space flight. Schirra had been reluctant to join NASA in the first place and was tired of the constant grind. Apollo 8 was the first successful flight to lunar orbit, with Borman’s backup being Neil Armstrong. According to Slayton’s roster, this put Armstrong in position for Apollo 11.

Spacecraft names came back with Apollo 9. They would be testing the lunar module for the first time and needed call signs. The crew decided to name the command module Gumdrop and the lunar module became Spider. Predictably, PR personnel hated the undignified names. Apollo 10 was even worse, with Snoopy for the lunar module and Charlie Brown for the command module. The PR staff must have felt like the astronauts were out to make their job difficult and insisted on dignified names from now on. Public Relations won that round and Apollo 11’s call signs became Columbia and Eagle.

Initially, it wasn’t certain that Apollo 11 would be the first lunar landing. If there were serious problems with 7, 8, 9 or 10, it could have gotten pushed back to 12. Even after they received the go-ahead with the landing, a lot of people had their fingers crossed and were out solving problems. Michael Collins spent a lot of time in the simulators going over possible rendezvous scenarios. Buzz Aldrin pushed for a decision on who would be the first to step on the lunar surface and Slayton finally told him it would be Armstrong based on seniority and the layout of the lunar module’s interior.

Apollo 11 launched on July 16th, 1969. Due to a series of mishaps, the Russians were not in a position to do much about it. They still had one last act of defiance in the form of an unmanned probe named Luna 15. It ended up crashing into the lunar surface. The Russians were sporting enough to call Neil Armstrong “the Czar of the Ship” and dedicate a launch to him after his successful return.

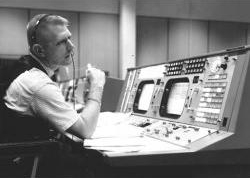

Deke Slayton sat in Mission Control the day of the landing, ready to offer advice or comfort in case something went wrong and they never made it off the surface. Armstrong thought the planned landing site looked too rough and took over the controls to look for a better spot. He did with only thirty seconds of fuel left to spare. “Houston, the Eagle has landed!” It was a proud moment for all of America.

Slayton was still determined to do something about the fibrillation that recurred about once a week. He tried everything, including a drug called quinadine, which was supposed to treat it but still would have meant that he would be ineligible for flight. Then, he discovered a secret weapon in the form of vitamins.

Back in the Game

By this point, Deke Slayton wasn’t likely to get an Apollo flight. However, things were beginning to look up. In April of 1970, he had a cold and the doctor suggested that he take vitamins. For three months, he went without a fibrillation and was on a hunting trip when he realized it. He kept notes and took them to NASA physician Chuck Berry. Now it was a matter of finding a specialist who could clear him for flight.

Berry took Slayton’s case to a medical conference in Turkey and met with Mayo Clinic’s Hal Mankin. Mankin agreed to test Slayton. It would be his last chance to be medically certified for flight. Slayton checked into Mayo Clinic under an assumed name and went through a week of testing. When the results came back, there was no sign of heart disease, not even fibrillation. Berry took the results to a panel of seven doctors who could give him the final clearance and they agreed. Slayton was finally back on flight status, ten years after they yanked him from his Mercury flight.

Slayton was thrilled but didn’t want to make a big deal out of it. NASA officials alerted the press anyway and a photographer from the Huntington Post was there to take photos of Slayton’s first solo flight since 1962. The next step would be getting an actual space flight.

Apollo-Soyuz Test Project

ASTP

The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) was an idea that had been in the works for some time. In the event of a disaster in space, a rescue might be necessary and one of the objectives was to create an international standard for docking equipment. The main obstacle was a diplomatic one. The U.S.S.R. was the only other country with a viable space program at the time and this was at the height of the Cold War.

The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) was an idea that had been in the works for some time. In the event of a disaster in space, a rescue might be necessary and one of the objectives was to create an international standard for docking equipment. The main obstacle was a diplomatic one. The U.S.S.R. was the only other country with a viable space program at the time and this was at the height of the Cold War.

During the 1970s, the Cold War began to thaw and the Russians were reportedly impressed by a movie called Marooned! in which a Russian cosmonaut takes part in rescue efforts for three stranded American astronauts. The formal agreement between the Russians and the Americans was signed in May 1972.

Marooned!

This movie demonstrated the reason that a universal docking system would be useful. After months on a Skylab-like space station, three astronauts are stranded in space when their thrusters malfunction. During efforts to rescue them, the Americans receive help from a surprising source.

Russian Lessons and Other Business

Deke Slayton recognized ASTP as the chance it was and slipped his name into his proposed prime crew for the American side. He also started learning Russian. The language lessons were a source of amusement for fellow astronauts. Slayton would struggle with it and a fellow astronaut’s rendition of Russian in an Oklahoma accent made him the butt of “Oklahomski” jokes.

Deke Slayton recognized ASTP as the chance it was and slipped his name into his proposed prime crew for the American side. He also started learning Russian. The language lessons were a source of amusement for fellow astronauts. Slayton would struggle with it and a fellow astronaut’s rendition of Russian in an Oklahoma accent made him the butt of “Oklahomski” jokes.

Apollo 14, featuring Alan Shepard’s famous lunar golf shot, came and went. Apollo 15 caused a scandal when somebody discovered that the crew had smuggled more than 400 unauthorized postal covers in their Personal Preference Kits. It made a lot of people angry, including Slayton, and he yanked the crew off backup crew duties for Apollo 17. An across-the-board investigation revealed some dealings that hadn’t been approved by NASA and forced Slayton to pull Jack Swigert off his planned prime crew for ASTP.

Soon after the successful Apollo 17, Chris Kraft called Slayton to his office and announced that Slayton, Tom Stafford, and Vance Brand would be the American crew for ASTP. Stafford would be the commander. That was a little deflating for Slayton, who was one of the Mercury astronauts and had always tried to give the senior astronaut the job of crew commander. He could understand the reasoning since Stafford had actually flown, and he counted himself lucky to get a flight.

It would be two and a half years between the public announcement of the ASTP crew in 1973 and the actual launch in July 1975. In the meantime, Slayton had plenty to keep him busy. In the aftermath of Apollo, preparations for Skylab were getting into full swing. They used leftover Apollo hardware for a lot of it. Slayton thought the Saturn used to launch the Skylab station looked strange without an Apollo CSM attached to it. Skylab faced problems during the launch, including a meteoroid shield and a solar panel that deployed prematurely and were damaged. The meteoroid shield was supposed to double as a shade to dampen the sun’s heating effects. The Skylab crew couldn’t be expected to function in 140-degree heat, so they postponed the crew launch and went to the drawing board for ideas. They developed a parasol for the sunshade and the first Skylab crew were able to repair the solar panel.

The Russians announced their crew for ASTP, Alexei Leonov and Valeri Kubasov, in May 1973. They came to the U.S. with their alternates two months later. Leonov reminded Slayton of Wally Schirra with his jokes and Kubasov, an engineer, was nice but quiet. Neither party spoke each other’s language very well and Slayton suspected the Russian translators who came along were KGB agents.

The Americans’ turn to visit Russia came in October. They stayed at the Hotel Intourist in “Star City,” a military complex that permanently housed three thousand people including several cosmonauts. One of Slayton’s team brought a suitcase full of snacks and made a wisecrack about having caviar for breakfast. This didn’t bother Slayton, who developed a liking for Russian food. They were always under surveillance except for one time when Slayton and Brand managed to lose their followers at a department store in Moscow.

During their next visit to Star City in July 1974, the American crew decided to test just how thorough Russian surveillance was. The Russians had built a hotel just for them and, while they were in their hotel room, they complained about having nothing to do and it would be nice to have a pool table. The next day, they found their pool table, which Slayton supposed was the only one in Russia. Another time, they griped about some Russian technicians who didn’t seem to be doing their jobs and they never had to deal with those technicians again.

The cosmonauts’ visit to America in September 1974 led to some efforts on the American side to get them away from their “minders” for a while. Slayton took Leonov, Kubasov and Stafford to a sporting goods store in his Camero, which had room for only four people. They also took a Learjet on a hunting trip to Wyoming. In the meantime, the Russians launched Soyuz 15 with the intention of docking with their Salyut space station, but they had difficulty with the docking mechanism and had to cut it short. An accident involving Soyuz 16 set off some political noise about the Russian safety record. The Russian dress rehearsal for ASTP was a success, however, and they were confident that they could proceed.

During the third and final American visit to Russia, Slayton, Brand and Stafford got a chance to tour the launch center at Baikonur, in Kazakhstan. The Russians made no secret of the fact that it was a military facility but made sure to fly them out at night and showed them only the hardware related to their “international” programs. Slayton was impressed by Russian efficiency. The on-site spacecraft assembly building had several Soyuz vessels in various stages of construction and the Russians could take them out to the pad only two days before a flight, as compared to weeks before for the Americans. The Americans became familiar with the Soyuz that was going to be used for ASTP and planted some trees, which was a tradition for cosmonauts before their flights. Then, they returned to Houston to prepare for their move to Cape Canaveral.

Into Space

The American crew moved into crew quarters on June 24, 1975 and limited their contact with people to avoid catching a last-minute bug. There was still some question about Russian reliability out in the “real world,” since their Salyuts kept failing. NASA continued to proceed confidently, for the most part. Slayton didn’t know it until afterwards, but there was still some concern on the medical front. Chuck Berry had left NASA soon after Skylab and two other physicians were insisting on a new flight rule. They wanted the launch to be delayed if Slayton fibrillated on the launchpad. Chris Kraft promptly called Berry, wanting to know what that was about. Berry went back to NASA twice to smooth some feathers and Kraft ended up getting the two physicians out of town until after the launch. Chuck Berry’s effort was vindicated when Slayton sent him the cardiac monitor used to track his heartbeat during the flight. Slayton did not fibrillate even once.

The American crew moved into crew quarters on June 24, 1975 and limited their contact with people to avoid catching a last-minute bug. There was still some question about Russian reliability out in the “real world,” since their Salyuts kept failing. NASA continued to proceed confidently, for the most part. Slayton didn’t know it until afterwards, but there was still some concern on the medical front. Chuck Berry had left NASA soon after Skylab and two other physicians were insisting on a new flight rule. They wanted the launch to be delayed if Slayton fibrillated on the launchpad. Chris Kraft promptly called Berry, wanting to know what that was about. Berry went back to NASA twice to smooth some feathers and Kraft ended up getting the two physicians out of town until after the launch. Chuck Berry’s effort was vindicated when Slayton sent him the cardiac monitor used to track his heartbeat during the flight. Slayton did not fibrillate even once.

In a rarity for the Russians, they agreed to broadcast the Soyuz launch live. Their launch occurred at midafternoon local time, while the Americans were still sound asleep. Slayton was already awake when John Young arrived with his wake-up call. It did feel a bit strange for Slayton to be on the receiving end because he was usually the one to wake the crews on launch day. They dined on steak and eggs, got suited up, and headed out to the launchpad. After only one brief delay caused by a tangled-up umbilical, the Apollo launched with Slayton on board.

They spent the next two days catching up with the Russian Soyuz, preparing the docking hatch, and conducting experiments. On July 17th, they spotted the Soyuz in the sextant and Slayton spoke to the cosmonauts for the first time. Stafford began the final approach and, at 11:09 Houston time, they made a successful docking. They received congratulations from Soviet President Brezhnev and American President Ford, exchanged flags, and signed ceremonial documents. Leonov proposed sharing a drink of vodka, saying it was a Russian tradition. Slayton took a swig and spluttered. The tube labeled “vodka” was full of soup. Slayton had just been the victim of an international gotcha.

During reentry, they had a problem with the RCS not closing and the cockpit filled up with yellow toxic gas. They were all coughing as they came down in the water and Slayton made the mistake of giving the frogmen outside a thumbs-up. Stafford retrieved gas masks. While on board the recovery ship, the doctors gave them a dose of cortisone and took chest X-rays. Slayton, Stafford and Brand all felt like they had pneumonia for a while. Slayton would soon realize how lucky he was. The X-rays turned up a benign lump in his lungs. If the doctors had known about it beforehand, he would never have gotten to fly.

After The Flight

Upon taking care of the post-flight work, Deke Slayton took charge of early tests of the space shuttle and then moved over to managing the Orbital Flight Test program. He retired from NASA in 1982 and went into business as president and vice chairman of Space Services Incorporated, which later merged with two other companies to become Space America. His relationship with Marge Slayton deteriorated and they divorced in 1983. He married again, to Bobby Osborne, later that year.

His death on June 13, 1993, led to one of the strangest stories involving Deke Slayton. About three and a half hours after he had died, an airplane known as the Williams Midget Racer, registered to the Slaytons, took off and performed aerial stunts. The high-speed propeller made so much noise that it violated FAA regulations and Deke Slayton’s widow received a citation for it. She had to call the FAA to explain that the propeller had to be spun by hand by someone outside the airplane before it would start and the engine had been removed from the airplane for display in a local museum. Later, she was heard to quip that maybe it had taken that long to find his friend Gus Grissom and get him to spin the propeller. The incident came to be known as “the last flight of Deke Slayton.” It remains an unsolved mystery.

More About Deke Slayton

Deke Slayton Collectibles

[ebayfeedsforwordpress feed=”http://rest.ebay.com/epn/v1/find/item.rss?keyword=Deke+Slayton+astronaut&sortOrder=BestMatch&programid=1&campaignid=5337337555&toolid=10039&customid=Deke+Slayton&listingType1=All&lgeo=1&feedType=rss” items=”15″]