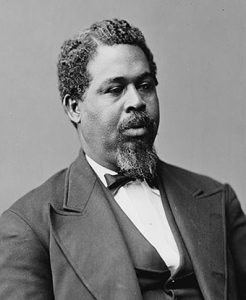

Gordon Cooper

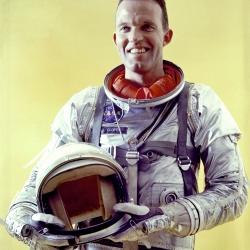

One of the Mercury 7 astronauts, Leroy Gordon Cooper Jr. flew the sixth and last Mercury mission in the Faith 7. He also flew the Gemini 5 mission. He preferred to be called Gordon Cooper, or just “Gordo” to his friends. He was the youngest of the original seven astronauts and once hoped to be the one who commanded a mission to Mars.

One of the Mercury 7 astronauts, Leroy Gordon Cooper Jr. flew the sixth and last Mercury mission in the Faith 7. He also flew the Gemini 5 mission. He preferred to be called Gordon Cooper, or just “Gordo” to his friends. He was the youngest of the original seven astronauts and once hoped to be the one who commanded a mission to Mars.

Shawnee, Oklahoma

Gordon Cooper had been flying for as long as he could remember. His father was a veteran military pilot who had served during World War I and owned a Commandaire biplane. By the time he was eight, his father was beginning to teach him the rudiments of flying and he was soloing by the time he was in his teens. This was at a time when aviation was just beginning to take off and not everybody was certain if there was a future in it outside of military applications. The few FAA regulations were not strictly enforced. His youthful flying did nearly get him into trouble once, when an FAA official spotted him doing stunts in a J-3 Cub. Cooper managed to talk his way out of trouble and had to promise not to let the official catch him doing that again. He kept that promise.

Cooper got a chance to meet many of the legends of aviation, including Amelia Earhart, Roscoe Turner and Wiley Post. He had a theory that Earhart’s dislike of radio communications contributed to her disappearance. She hadn’t upgraded her radio before taking her final flight. Roscoe Turner was most famous for racing planes, setting transcontinental speed records and owning a lion cub that Cooper later saw in his full-grown size. Roscoe apparently loved his lion so much that he had it stuffed after it died. Wiley Post set altitude and distance records, was the first to develop and use a pressure suit for high-altitude flying, and was the first to fly around the world solo. Cooper thought that was pretty good for a man who had lost an eye in an oil-field accident and it was a real tragedy when Post lost his life in a flying accident.

His mother had been a teacher before he was born, and both his parents insisted that he get a good education. They were avid travelers and Cooper would often bring schoolwork along on long camping trips. He took every high school class in aeronautics he could and signed up for formal flight training during his junior year. His parents taught him the value of earning his luxuries by giving him a lawn mower and he also found work at a local airport.

World War II began while he was still in school and he turned down a football scholarship at Oklahoma A&M to enlist in the Marine Corps when he was seventeen years old. He missed the chance to see combat and was sent to the Naval Academy Prep School in 1945. From there, he became part of the Presidential Honor Guard and sometimes had coffee with President Truman when he sneaked away from the Secret Service to take a walk. Truman was perfectly willing to share stories of his World War I experience.

He was discharged in 1946 and attended the University of Hawaii. He also joined the Army ROTC and bought another J-3 Cub from a couple who was moving out of Hawaii. He majored in engineering but did not get the best grades. He claimed it was the distractions that lingered on every beach. He stuck it out, though, and met another pilot named Trudy. They hit it off and were soon married. He got a regular Army commission in 1949 and moved over to the Air Force, where his flying experience paid off.

Flying In The Air Force

The first plane Cooper flew in the Air Force was the T-6 trainer. The T-6 was not an especially tricky plane to fly but did require that the pilot remain attentive. He hadn’t told anyone that he already had flying experience but his instructor quickly realized it and Cooper soloed on his third flight. He found out what it felt like to get paid to do something he loved. He probably would have spent every waking moment in the air if he could get away with it and freely admitted that he could be a grouch if he hadn’t flown recently.

Upon graduation, he was assigned to Munich, Germany, where he joined the 86th Fighter Bomber Group, flying F-84s and F-86s. He also earned some college credit at the European Extension of the University of Maryland. Duty was fairly tame though he did claim to have chased some UFOs and they certainly chased off Russian MIGs who strayed over the border. The Russians eventually learned to stay on their own side of the border.

Returning to America, he finished up his degree and reported to the Air Force Experimental Flight Test School at Edwards Air Force Base. He graduated in 1957 and became an aeronautical engineer and test pilot at Edwards. In May, 1957, two of the men he worked with came running in with pictures they had gotten of a flying saucer that had zoomed right over their heads. Cooper knew these were solid men who weren’t inclined to get worked up over nothing. He promptly reported the incident and a general ordered him to develop the film but not run any prints. Cooper got a good look at the developed film. It was a flying saucer, all right. The film was shipped off to Washington and he never saw it again. To his knowledge, the incident was never investigated as closely as it might have been, either. From then on, he was critical of Project Blue Book, calling it merely a way to placate the general public. He knew that not every report was being made by crackpots or marginal people.

Later that year, he had more to think about than UFOs. Russia launched Sputnik in October 1957, setting off a whirlwind of activity in the U.S. NASA was created and inherited the resources and many of the top brains of its predecessor, NACA. In January 1959, Cooper received orders to report to the Dolly Madison House in Washington, D.C. He had only guesses about what this was about. It turned out that he was one of 110 candidates, pulled from across three services, to join NASA as an astronaut.

Astronaut Candidate

Gordon Cooper’s commanding officer, General Cooper (probably no relation), called him and two other candidates into his office to talk about it. One of them was Deke Slayton, who would become a fellow Mercury astronaut.

General Cooper asked, “Do any of you know what this is about?”

They didn’t, and General Cooper didn’t know much more. He had read in the paper that a contract had been awarded for the new manned space program and warned them to be very careful about what they volunteered for. In the meantime, the U.S. Navy’s Vanguard exploded on the launchpad. That didn’t inspire much confidence but the missiles being developed at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, looked promising.

The candidates met for the first time on February 2. Some were more enthusiastic than others but response was generally positive and only a few backed out. Cooper’s only hesitation had to do with leaving Edwards for a brand-new agency with a still-uncertain future. He was intrigued by the challenge and, like most pilots, wanted to find ways to fly higher than anyone ever had before. He went on to the intense psychological and medical testing at Lovelace Clinic in New Mexico and Wright-Patterson in Ohio with a group that included Alan Shepard, a test pilot from Pax River.

Space medicine was a new science and, at that point, all the doctors had were guesses about what would happen to the human body above Earth’s atmosphere. They came up with the most rigorous testing they could think of and many of the candidates theorized that the doctors were testing their reaction to a high-stress environment. Gordon Cooper was one of two candidates with allergies, the other being Gus Grissom, but managed to convince the doctors that allergies wouldn’t be much of a problem in outer space.

Cooper ended up having some fun with the doctors. When they dunked him in ice water, he told them, “This is just like trout fishing in the mountains back home.” One of the doctors made a note on his pad that he liked it. When they put him in a room heated to 160 degrees to test his reaction to heat, he said, “I’m back in the desert. This is the temperature we fly in all the time at Edwards.” Perhaps not realizing that Cooper was teasing them, they put a note on their pads that he liked the heat. He was one of several candidates who took a nap when they put him in a blackout chamber.

He went back to Edwards, feeling confident about his chances. When his phone rang, he knew right away that it was good news. Picking up the receiver, he told the man, “I’m ready.” That must have gotten a raised eyebrow on the other end. “Good; when can you leave?” “How about right now?” “Next Monday will be fine.”

By this point, he and his wife, Trudy, had separated and Cooper called her to convince her to move back in, if only to create the illusion of a happy family life. On April 9, 1959, he reported to the Dolly Madison House to attend the press conference with the other Mercury astronauts.

The Press Conference

Astronaut Training

Nobody had ever done anything quite like this before. Many of NASA’s employees were used to working in aeronautics and now they had to adjust their thinking for astronautics. It meant new guidance systems, new monitoring systems, and even a new method for soldering to keep the rockets from disintegrating. The Mercury astronauts were invited to give their input and did at every opportunity. One of their first contributions was a patch for the Mercury Program: the Greek symbol for Mercury with the number “seven” inside to denote the seven astronauts. They flew all over the country to different contractors and were occasionally asked to give pep talks. John Glenn was best at this, and “Gloomy Gus” Grissom had one shining moment when he came up with a three-word speech: “Do good work.” The workers loved it.

Nobody had ever done anything quite like this before. Many of NASA’s employees were used to working in aeronautics and now they had to adjust their thinking for astronautics. It meant new guidance systems, new monitoring systems, and even a new method for soldering to keep the rockets from disintegrating. The Mercury astronauts were invited to give their input and did at every opportunity. One of their first contributions was a patch for the Mercury Program: the Greek symbol for Mercury with the number “seven” inside to denote the seven astronauts. They flew all over the country to different contractors and were occasionally asked to give pep talks. John Glenn was best at this, and “Gloomy Gus” Grissom had one shining moment when he came up with a three-word speech: “Do good work.” The workers loved it.

They shared an office with seven desks and a single secretary named Nancy Lowe, who was just starting a 25-year career at NASA. Cooper came to admire her ability to stay organized and keep up with seven alpha-male bosses. In that office, they caught up with each others’ work and hashed out differences so they could take their recommendations to NASA officials as a team. One thing they agreed on was the need for a window in case the automated systems failed and the astronaut had to take manual control. It turned out to be a wise decision. Disagreements included whether they wanted rudder pedals for yaw, or side to side, control or a simpler three-axis control stick. They went with the control stick.

They chose specializations so they could split up the work and Cooper got propulsion systems; essentially, the rockets and thrusters on the capsules. That meant he was at Huntsville, Alabama, and the Redstone Arsenal a lot. He developed a good working relationship with Wernher von Braun, who had started his career developing the V-2 rockets that slammed into London during WWII and came over to America as part of Operation Paperclip after the war.

Training took up nearly as many hours as their specializations and Cooper pulled up to 18 Gs in the centrifuge. That many Gs felt like he weighed 2700 pounds, about the equivalent of having a Mack truck parked on his chest. He was barely able to remain conscious and had a glaring red pattern of busted capillaries on his back when it was over. They eventually agreed that 15 Gs was the practical training limit.

At first, NASA had no planes and it cut so much into their flying time that their flight pay was at risk. Like the rest of the astronauts, Cooper was not happy about it and complained to New York Congressman Jim Fulton. He told Fulton that flying ought to be an integral part of astronaut training. Fulton opened an investigation into the matter, ticking off some NASA officials but delighting the astronauts when some F-102s showed up. Later, NASA would get some T-33s and T-38s for their astronauts.

Watching the test launches could be both uninspiring and risky. One test aborted when an electrical cord pulled free too early, causing the engines on the rocket to shut down. The rocket settled back on the launch pad and sat there like nothing had happened. Another time, both Cooper and Gus Grissom were flying chase on a rocket launch. Their job was to go up in F-106s to observe the flight up close. Grissom would make his approach at the 5000-feet level and fire his afterburner to climb in a spiral along with the rocket. Cooper would take over at the 15,000-feet level. Something went wrong and Mission Control decided to hit the abort button. The first warning Cooper got came when he saw the escape tower pull the capsule away from the rocket, missing his plane by all of fifteen feet. Then, the rocket exploded and Cooper had to hightail it out of there to avoid flying debris. He thought he saw Grissom flying through the fireball. It was a minor miracle that neither of their planes were damaged.

With all their hard work, being able to let off steam at the end of a long day was essential. Most of them leased high-performance sports cars and went drag-racing. Those cars became fair game for any number of pranks. Gene Kranz remembered his first meeting with Cooper, who offered him a ride after he landed at Cape Canaveral for the first time to start his new job as assistant flight controller. Cooper peeled away from the plane and floored it. Kranz became convinced that he had hitched a ride with a speed demon intent on breaking every regulation he could in the shortest time possible. He hit the highway, burning rubber at about 90 miles per hour. Then, he introduced himself, quite cool: “Hi, I’m Gordo Cooper.”

The endless rounds of the “Gotcha!” competition spilled over to friends both inside and outside NASA. One such friend was a hotel manager named Henri Landwirth, who, luckily, had a sense of humor. One time, Cooper took his fishing rod and a cooler full of live fish along to Landwirth’s Holiday Inn in Cocoa Beach, Florida. Of course, Landwirth spotted him and asked what he was up to.

“I’m fishing.”

“Fishing. In my swimming pool.”

Cooper dumped those fish into the swimming pool. “I’ll catch these.” Some of the other guests weren’t too thrilled about sharing the pool with fish that started floating belly-up but Landwirth chalked it up to typical astronaut exuberance.

Each of the astronauts hoped to be the first man in space and, inevitably, Bob Gilruth called them all together to announce his selection. Alan Shepard was going to be first, with John Glenn as his backup. Cooper tried to swallow his disappointment but reassured himself that he he had a chance at a better assignment on down the road. He would, but it would be close.

Mercury

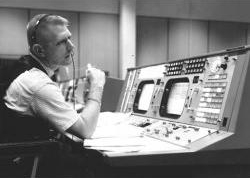

NASA began the long-standing tradition of putting an astronaut in the Capsule Communicator (Capcom) position by asking Gordon Cooper to take the slot for Alan Shepard’s flight. They began the long, three-hour wait through all the delays. It was inevitable that Shepard put in an urgent call:

NASA began the long-standing tradition of putting an astronaut in the Capsule Communicator (Capcom) position by asking Gordon Cooper to take the slot for Alan Shepard’s flight. They began the long, three-hour wait through all the delays. It was inevitable that Shepard put in an urgent call:

“Gordo.”

“Go, Al.”

“I gotta go pee.”

“You’re kidding me.”

But Shepard wasn’t. Informed that he couldn’t leave the spacecraft, he began to lose his temper and threatened to go in his suit. The technicians worried about how this would short-circuit the electronics in the pressure suit and Shepard barked at them to turn it off. Cooper had to negotiate with the techs, who agreed. Shepard became the first documented case of a space flier becoming a wetback in his spacecraft and nobody was particularly surprised when he made his famous snap, “Why don’t you fix your little problem and light this candle?” He finally made his suborbital flight and they recovered him in good shape.

Gus Grissom’s flight in the Liberty Bell 7 was also a success, though his capsule sank. The hatch had blown apparently of its own accord, causing the capsule to become weighed down with sea water. Though popular opinion had it that Grissom had blown the hatch himself, he was cleared by a review board and went on to fly the first manned Gemini flight.

John Glenn had a successful first orbital flight in the Friendship 7, followed by Scott Carpenter’s Aurora 7 and Wally Schirra’s Sigma 7. They were planning a final, day-long orbital flight to round out the Mercury program. The question was, Who would fly this one?

Faith 7

Gordon Cooper was assigned to the flight, but it wasn’t necessarily set in stone. Alan Shepard became his backup and made no secret of the fact that he wanted one more Mercury flight, or, failing that, the first Gemini flight. Some were concerned about Cooper’s daredevil stunts even though he wasn’t the only one to pull them. Others didn’t like his Oklahoma accent, thinking it made him sound like a hillbilly. Deke Slayton had taken charge of the Astronaut Office by this point and pointed out that it wouldn’t be fair to keep Cooper sitting on his hands. It was either fly him, or send him back to the Air Force. So the higher-ups at NASA headquarters went along with it.

Gordon Cooper was assigned to the flight, but it wasn’t necessarily set in stone. Alan Shepard became his backup and made no secret of the fact that he wanted one more Mercury flight, or, failing that, the first Gemini flight. Some were concerned about Cooper’s daredevil stunts even though he wasn’t the only one to pull them. Others didn’t like his Oklahoma accent, thinking it made him sound like a hillbilly. Deke Slayton had taken charge of the Astronaut Office by this point and pointed out that it wouldn’t be fair to keep Cooper sitting on his hands. It was either fly him, or send him back to the Air Force. So the higher-ups at NASA headquarters went along with it.

He named his capsule the Faith 7, making some PR people nervous. They could just see the headlines if it turned into a disaster: “NASA loses Faith!” But they painted it on the side of his capsule anyway.

Everything went well right up to the last minute. Then, Cooper discovered that somebody had made a last-minute change to his suit to add another monitor. He was furious. They had just violated a rule that they couldn’t make changes to the suit right before the flight. What if the thing leaked? Still fuming, he vented while flying in an F-102, which had become a day-before-the-flight ritual. He went through the usual loops and dives, and then made a mistake that almost cost him the flight. He went into a dive and hit the afterburner right above the main NASA building. This rattled windows and several people’s nerves, including Walt Williams.

Williams went straight to Deke Slayton, insisting that Cooper be replaced on the flight. Slayton did his best to placate Williams, explaining that flat-hatting was a common pilots’ practice and telling him that perhaps they could sweat him a bit. Shepard got wind of Williams’ fury and let word get around that he would be perfectly happy to take the flight. Slayton later told Cooper that Kennedy had also heard about Williams’ intention to yank him off the flight and insisted that he stay. Walt Williams backed down.

Launch Day

May 15, 1963

His morning started like any other launch day. He had a generous breakfast of filet mignon, eggs, toast with grape jelly, orange juice and coffee. While he got into his flight suit, he took some joking from the flight surgeon and a few of his fellow astronauts. Cooper recognized it as a valiant attempt to keep him relaxed. He rode out to the launch pad and met with Guenter Wendt, another German rocket scientist, and saluted. “Private Fifth-Class Cooper reporting for duty.” Wendt saluted back, “Private Fifth-Class Wendt standing by.” It was a reference to a joke they had played on reporters just a few days before. The news men had gotten a chance to see what a normal launch day might look like. Cooper pretended to balk at the gantry elevator and let out a mock-terrified holler. “No! No! I don’t want to go!” Guenter pulled him inside. One humorless reporter suggested that they both be busted to “Private Fifth-Class.”

During the Mercury days, it wasn’t uncommon for the astronaut riding the rocket to be the least nervous person in NASA, and Gordon Cooper was no exception. He hadn’t gotten a lot of sleep the night before and actually fell asleep on the launchpad during a delay to track down a glitch. This had some of the doctors who noticed his low heartbeat to scratch their heads until they figured out that he was just dozing. Now, it was almost launch time. “Gordo!” Wally Schirra, at the CapCom position, woke him up. “Hate to disturb you, old buddy, but we have a launch to do here.” Instantly alert, Cooper answered, “Let’s do it.”

During the Mercury days, it wasn’t uncommon for the astronaut riding the rocket to be the least nervous person in NASA, and Gordon Cooper was no exception. He hadn’t gotten a lot of sleep the night before and actually fell asleep on the launchpad during a delay to track down a glitch. This had some of the doctors who noticed his low heartbeat to scratch their heads until they figured out that he was just dozing. Now, it was almost launch time. “Gordo!” Wally Schirra, at the CapCom position, woke him up. “Hate to disturb you, old buddy, but we have a launch to do here.” Instantly alert, Cooper answered, “Let’s do it.”

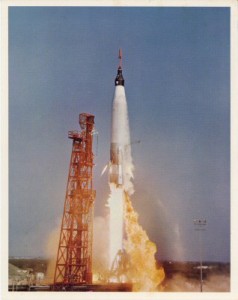

Minutes later, the engines were lit. “We have liftoff!” Wally said. Cooper started the clock. “Roger, liftoff. The clock has started.” The rocket went through some teeth-rattling vibrations as it accelerated through the atmosphere and hit Mach 1 in twenty seconds. Then, it smoothed out and reached 17,549 miles per hour in five minutes, the speed necessary to make it into orbit. He went from nine Gs to none at all. Faith 7 separated from the Atlas rocket, which would re-enter the atmosphere and plummet into the Pacific Ocean. He took over the controls and adjusted the capsule to the attitude necessary for re-entry. If something went wrong, he would be ready. Cooper had insisted on having a chance to adjust to weightlessness and admire the view and, when he looked out the window, he was glad he did.

He could see much of the East Coast, from Florida up to Virginia, and then the continent of Africa. He noticed it was getting uncomfortably warm in the cabin, a result of the friction of passing through Earth’s atmosphere. This had been a problem on previous flights and he adjusted the setting on the cooling system to a more tolerable 92 degrees.

His attempt to launch a balloon to test atmospheric drag failed but an experiment with a sphere that would fly separately from the capsule and flash a strobing light to test his ability to see it was more successful. He also took several pictures of the Himalayas, wondering why photography wasn’t as important to NASA scientists as it would be in later years. John Glenn had insisted on taking a camera along on his flight and, after that, NASA simply stated that cameras were optional for the Mercury flights. Then, he was scheduled for some sleep. Due to the lack of gravity, his cardiovascular system didn’t have to work so hard to pump blood and his heart rate dropped so low that Mission Control woke him up to make sure he was okay. He also earned some ragging from Deke Slayton for using less oxygen than expected. Unlike the other astronauts, he had never smoked in his life.

Since the Faith 7 was doing well so far, Cooper got the go-ahead for the planned 22 orbits. On the sixteenth orbit, he took several pictures of the horizon at sunset. MIT would analyze these photographs to see if the horizon would be a reliable way for astronauts to orient themselves on lunar trips. They decided to go with the fixed position of stars instead.

Things went well until the nineteenth orbit. A green light came on, indicating that he had begun reentry. Mission Control noticed it, too, and asked about it. “Like hell!” responded Cooper. Mission Control made several suggestions that sounded to Cooper like they were grasping at straws. It was only the beginning of the malfunctions. A series of shorts fried the telemetry and most of the electrical systems. The cooling system went out and, with it, the ability to scrub carbon dioxide from the air. Cooper could still talk to the ground only because his radio was on a separate power system. Because the telemetry was out, his reports were the only way Mission Control knew what was going on in orbit. He was going to have to reenter before the rising levels of carbon dioxide incapacitated him.

His gyroscopes and on-board clock were gone, and also the automatic attitude control system. The manual controls still worked. This was Cooper’s chance to put an end to all the jokes from other pilots about “Spam-in-a-can” and being put on the same level as the chimps NASA had used on some test flights. He would have to fire his retro-rockets to slow Faith 7 down and Mission Control told him to take his timing from his watch, with John Glenn giving him a countdown as a backup. He oriented his capsule for reentry and had to keep a clamp on yaw.

Temperatures were soaring. It reached 110 degrees in his pressure suit and 130 in the cabin. Carbon dioxide levels were becoming intolerable. On Glenn’s countdown, he fired the retro-rockets and Cooper had to keep on top of the oscillations it caused. He had trained in the MASTIF for a capsule that tumbled out of control and Faith 7 could have done exactly that if he wasn’t careful. If that happened, he would have lost the protection of the heat shield and been exposed to 3,000-degree heat. He went through the radio blackout caused by the heat and ion buildup, and then made contact with Scott Carpenter in Hawaii.

“How you doing?” asked Carpenter.

“Fine.”

Cooper had to deploy the parachutes manually and splashed down. He had come down a mile closer to the recovery ship a mile closer than Wally Schirra had in the Sigma 7, winning a bet. He though he could have landed right on the aircraft carrier Kearsage‘s deck if it wasn’t for wind drift. He felt shaky and his arm felt heavy when he saluted the captain. He was whisked off to the first of several rounds of debriefings and medical testing.

Cooper had to deploy the parachutes manually and splashed down. He had come down a mile closer to the recovery ship a mile closer than Wally Schirra had in the Sigma 7, winning a bet. He though he could have landed right on the aircraft carrier Kearsage‘s deck if it wasn’t for wind drift. He felt shaky and his arm felt heavy when he saluted the captain. He was whisked off to the first of several rounds of debriefings and medical testing.

Deke Slayton congratulated him for a job well done and Walt Williams admitted that he had been wrong. “Gordo, you were the right guy for the job.”

Cooper’s response was an exaggerated version of his Oklahoma accent: “Aw, shucks, we aim to please.”

America Welcomes a Hero

Joint Session of Congress

When Cooper returned to the States, he received an invitation to speak before a joint session of Congress. Julian Scheer, the deputy director of NASA Public Relations, handed him a prepared speech. Cooper handed it back.

“I’m not giving this speech.”

“Oh, yes you are.”

“No I’m not.”

Scheer tried to insist, but Cooper turned to some NASA officials. “Get this guy out of here before I deck him.” Scheer avoided him for a week. Then, Cooper faced a press conference. The PR people had made efforts to improve the astronauts’ ability to speak to the press, and it showed. Cooper even made a joke about being the first American to sleep in space: “I can safely say that I’ve answered with finality the question of whether sleep is possible during space flight.”

Cooper’s refusal to make a prepared speech caused some concern at NASA. Slayton relayed Bob Gilruth’s doubts to Cooper: “Gordo, Bob is a little concerned. He’s never heard you give a speech before.”

It was true. Cooper had gone out of his way to avoid giving speeches whenever possible. Gilruth was wondering if he was up to the job. So, Cooper showed Slayton some notecards he had made notes on. Slayton relayed that to Gilruth and came back with only one change. They wanted him to include a prayer Cooper had recited into his recorder during his flight. Cooper hadn’t meant it for the general public but accepted it anyway.

Cooper got a standing ovation when he walked into the House of Representatives chamber. The speech came off well though one newspaper did criticize him for his hillbilly style of talking. Later, he was asked about a comment that a Russian cosmonaut had made about not finding God out there. Cooper responded that if he hadn’t known God on Earth’s surface, he wasn’t going to find Him at an altitude of 150 miles.

Gemini

NASA added nine more astronauts to the roster to help with the two-man Gemini flights. Of the Mercury astronauts, John Glenn had left in frustration because Gilruth seemed reluctant to give him another flight and Scott Carpenter was showing interest in the Navy’s Sealab. The rest of them were going nowhere quite yet. To help prepare, Carpenter teamed up with Pete Conrad.

NASA added nine more astronauts to the roster to help with the two-man Gemini flights. Of the Mercury astronauts, John Glenn had left in frustration because Gilruth seemed reluctant to give him another flight and Scott Carpenter was showing interest in the Navy’s Sealab. The rest of them were going nowhere quite yet. To help prepare, Carpenter teamed up with Pete Conrad.

A malfunctioning spacecraft could land them in a place where they might have to fend for themselves for up to a week, so NASA had added survival training to the roster. Jungle training proved interesting. They would live off whatever they could catch, and that included piranhas. Cooper admitted to using Conrad as bait and they discovered that grilled piranha tasted pretty good. They encountered some of the local Choko Indians who didn’t seem to quite believe Cooper when he explained that they were preparing to go into space. The Chokos helped them improve their technique, including showing them how to set snares for small game, and the two astronauts even got to visit their village. Cooper later heard that the Choko chief received a medal for helping the astronauts.

Cooper and most of the rest of the astronauts felt that NASA administrator James Webb made a bad mistake when he declared that American spacecraft would no longer have names. NASA officials hadn’t liked it when Gus Grissom named Gemini 3 the Molly Brown and Cooper considered Webb’s intention to “depersonalize” the space program an overreaction. Spreading the word about their scientific progress was okay, Cooper thought, but the American public also wanted to hear the personal side of things. Early on, the Mercury astronauts had worked out a deal with Life magazine that would allow people to see who the astronauts were as people without having reporters camping on the astronaut families’ front lawn, and now Webb was reversing course. Cooper did have one minor victory. For Gemini 5, he designed a patch with a covered wagon and the phrase “Eight Days or Bust.” Webb wasn’t too fond of the “Eight Days or Bust” bit, either. The mission could be seen as a failure if it didn’t make it the whole eight days. That and future patches came to be known as Cooper patches.

Cooper and most of the rest of the astronauts felt that NASA administrator James Webb made a bad mistake when he declared that American spacecraft would no longer have names. NASA officials hadn’t liked it when Gus Grissom named Gemini 3 the Molly Brown and Cooper considered Webb’s intention to “depersonalize” the space program an overreaction. Spreading the word about their scientific progress was okay, Cooper thought, but the American public also wanted to hear the personal side of things. Early on, the Mercury astronauts had worked out a deal with Life magazine that would allow people to see who the astronauts were as people without having reporters camping on the astronaut families’ front lawn, and now Webb was reversing course. Cooper did have one minor victory. For Gemini 5, he designed a patch with a covered wagon and the phrase “Eight Days or Bust.” Webb wasn’t too fond of the “Eight Days or Bust” bit, either. The mission could be seen as a failure if it didn’t make it the whole eight days. That and future patches came to be known as Cooper patches.

The two-man Gemini spacecraft were 50% bigger than their Mercury counterparts. While developing them, some systems became streamlined, making for even more room. Some ideas that had been batted around for Gemini had been discarded, such as a glider that would have allowed the Gemini to land at Cape Canaveral. The idea of a gliding, reusable spacecraft wouldn’t be implemented until the start of the space shuttle program. In the meantime, crews were drawn up for the twelve manned Gemini flights and Gordon Cooper and Pete Conrad were assigned to Gemini 5.

Cooper was again assigned as CapCom for Gemini 3 and managed to get Grissom’s name for the spacecraft into the history books during launch: “You’re on your way, Molly Brown.” The press loved it. The flight of the Molly Brown was a success, and so was Gemini 4, featuring the first American spacewalk by Ed White. Then, it was Cooper’s and Conrad’s turn.

Gemini 5

August 21-29, 1965

The launch of Gemini 5 was much smoother and quieter than it had been on Cooper’s Mercury flight. Gemini 5 was the first to make use of an electrochemical generator instead of batteries for power, a necessity considering the amount of electronics on board. The generator would last for as long as there was hydrogen and oxygen it could convert into power.

The launch of Gemini 5 was much smoother and quieter than it had been on Cooper’s Mercury flight. Gemini 5 was the first to make use of an electrochemical generator instead of batteries for power, a necessity considering the amount of electronics on board. The generator would last for as long as there was hydrogen and oxygen it could convert into power.

On the third orbit, the generator’s oxygen level dropped from 800 pounds per square inch (psi) down to 70 psi without warning and Cooper began flipping power switches to the off position to conserve power. The sudden drop almost cost them the mission as Mission Control debated ordering an abort. That would have set back the space program by a few years, something they could not afford if they wanted to reach the moon by the end of the decade. Cooper had pushed for extra tests on the generator; NASA didn’t have the money for them in the budget but Jim McDonnell, who headed up contractor North American Aviation, paid for them. It ended up saving the mission. Cooper and Conrad tracked down the problem: a faulty heating system that wasn’t converting the liquid oxygen into a gas. They were able to gradually reverse the problem and bring their power back up to nominal levels over the next several days. Mission Control canceled the experiments that required fuel and the problem would be fixed for later flights.

Now, they were able to remove their helmets and gloves and stow them in compartments near their feet and do a little sight-seeing. Conrad hadn’t believed Cooper when he said he could make out details like ship’s wakes. Now Conrad did and was impressed by the view. They would perform vision experiments periodically, including looking for a checkered layout in Texas and Australia and reading from an in-flight vision tester. Their vision remained unchanged throughout the flight.

Flying over China, they heard a high-pitched pinging sound that turned out to be radar. China had protested the flyover of Gemini 5 when told that they would be using cameras with telephoto lenses, accusing them of spy activity. Now that it was actually happening, they took a different tack. A feminine voice Cooper guessed was Peking Peggy came up to them: “Good evening, Gemini 5. For your pleasure we will play some music.” In a thoughtful gesture, Peking Peggy piped up some opera music for them.

At first, they tried sleeping one at a time with the other remaining awake and on watch. This didn’t work as well as they hoped; Mission Control’s calls kept waking the sleeper up. Finally, Cooper insisted on uninterrupted sleep and Mission Control agreed that they could sleep simultaneously.

On the third day of their mission, they rendezvoused with an imaginary target. They made four adjustments to their orbit using their orbital attitude-maneuver thrusters, changed the shape of their orbit from circular to elliptical, and came within a tenth of a mile of their goal. They also tested their radar by aiming it at a radar transponder at Cape Canaveral. There had been some question of whether the radar equipment would have survived the launch. It did, and proved accurate to within three miles.

Cooper and Conrad were also the first to observe a meteorite shower from space. Astronomers had alerted them to watch for a shower that happens every August. Thousands of meteorites whizzed past their spacecraft, putting on an impressive show for them. They knew it was possible that one of these falling rocks could hit their spacecraft and were prepared to patch up any small punctures. Suddenly, Gemini 5 was whacked by a meteorite that was no bigger than a pebble but sounded like someone had thrown a fastball at their spacecraft. The bang made them both jump. If the particle had been any bigger, it could have gone right through the hull, ending the mission and quite possibly their lives. They were hit a few more times during the next few days and an analysis of the spacecraft revealed quarter-inch dents in the titanium hull.

They took pictures whenever they could and, when they returned to Earth, Cooper was infuriated when the pictures were promptly classified. He was later told that many of the pictures would be declassified. In fact, the initial reaction was due to the fact that he had inadvertently taken pictures of Area 51! Considering the speculation surrounding Area 51, he considered it ironic that a spaceman should be the first person to come home with pictures of America’s most famous secret facility.

Gemini made use of of a computer designed specifically for the job and Houston would periodically send up data about their orbit. They checked it out before inputting it but were so busy during one upload that they only gave it a cursory once-over. It got them in trouble during the reentry sequence. They came into the atmosphere steeper than they should have, not enough to put them in danger but enough that they were going to splash down short of their goal. Gemini had been modified from the Mercury system of just falling once gravity took over and Cooper again had to take control. He ignored the erroneous readouts and lengthened their glide. He managed to make up 150 miles of lost ground and Gemini 5 splashed down only 100 miles short. The helicopter recovery crew spotted them 45 minutes later and took them back to the USS Lake Champlain. Cooper later learned that the error was due to a mistake made by mathematicians and astronomers. They had worked on the assumption that the Earth rotates 360 degrees in a day, when in reality it rotates 359.999 degrees. Over the course of the eight day mission, the seemingly small error had added up. It was the first lesson NASA got on using the correct figures.

World Tour

After the successful Gemini 5, President Johnson loaned Air Force One to Peter Conrad and Gordon Cooper for a goodwill tour to Greece and Africa. In Athens, Greece, they gave talks about their flight to the 16th International Astronautical Congress. By this point, he had made amends with Julian Scheer. At Athens, Scheer pointed out two Russian cosmonauts in the crowd named Pavel Belyaev and Aleksey Leonov. Leonov was the first man to go EVA and Belyaev had been commander of that mission. After Cooper made his speech, he went over to shake hands and earned a standing ovation for it.

King Constantine II and the Queen Mother Frederica of Greece invited the astronauts and cosmonauts over for a cocktail party. Cooper was able to converse with Belyaev in Spanish and German and they traded the wristwatches they had worn during their flights. Cooper invited them over to their hotel suite for breakfast the next morning. They talked shop and, when the cosmonauts admitted that the Russian space program had experienced fatalities during reentry, Cooper made a sketch of a drogue chute. Russian spacecraft were soon seen equipped with nearly identical chutes and Cooper refused to believe it was a coincidence. Their meeting in Greece began a friendship that lasted until Belyaev died several years later.

They went from Greece to Ethiopia, where they met Emperor Haile Selassie. When Cooper stepped off Air Force One, the very first thing he saw was a lion who appeared to be sizing him up as potential prey. Cooper had to squash his fight-or-flight reflex. For Selassie, bringing along his prized pet lion was no different from an American bringing his pet dog along to a picnic. Emperor Selassie was interested in the space program and asked several questions.

They stayed at the emperor’s palace and Cooper’s daughters got to pet two cheetahs that stood alongside Selassie’s guards. Selassie warned them not to stay out too late, because his prized pets were allowed the run of the grounds at night to help discourage intruders.

Cooper took his family shopping and alerted Selassie about one booth that was openly selling slaves, which was illegal in Ethiopia. The booth was shut down quickly. Cooper considered it a shame when Selassie was killed in a socialist uprising. Ethiopia went downhill fast after his death.

Their next stop was Kenya. Jomo Kenyatta was a revolutionary leader who had successfully led efforts to free Kenya from English rule and had been elected its first president. Kenyatta met them at his hunting lodge in the middle of a game preserve and invited them to inspect his troops, seven-foot-tall Masai warriors who stood in ranks with discipline that impressed Cooper. As Cooper looked one especially tall warrior over, the man asked a question in his native language. The interpreter translated it: “Sir, after your fuel cell problem, how did the phantom radar rendezvous turn out?” Cooper politely answered the question and then asked the interpreter how the Masai had heard about that. “Transistor radios,” the interpreter grinned. “Voice of America carried your flight live in Swahili.”

Fire In The Cockpit!

Most of the rest of Gemini went reasonably well with the biggest problem being a malfunctioning thruster on Gemini 8 that forced an early return. Apollo, however, was not shaping up so well. Part of the problem was that chief NASA officials had gone with a new and inexperienced contractor that turned out a defective spacecraft. NASA management did not seem to take the problem very seriously and just assumed that things would be sorted out before the scheduled flight. Cooper had spoken with Gus Grissom the night before the scheduled “plugs-out” test and remembered that Grissom was feeling discouraged about it.

Most of the rest of Gemini went reasonably well with the biggest problem being a malfunctioning thruster on Gemini 8 that forced an early return. Apollo, however, was not shaping up so well. Part of the problem was that chief NASA officials had gone with a new and inexperienced contractor that turned out a defective spacecraft. NASA management did not seem to take the problem very seriously and just assumed that things would be sorted out before the scheduled flight. Cooper had spoken with Gus Grissom the night before the scheduled “plugs-out” test and remembered that Grissom was feeling discouraged about it.

Cooper was in Washington, D.C., celebrating the signing of the Peace in Space Treaty aimed at preventing hostilities in space, and decided to turn in early after the official ceremony. He had just returned to his hotel room when the phone rang. Congressman Jerry Ford was on the other end.

“Gordo, I just got word that there’s been an accident at the Cape and the crew was killed.”

Cooper was stunned. He and Gus Grissom had been best friends, relaxing together and supporting each other when they were having a bad day. And now Grissom was dead, along with Ed White and Roger Chaffee. In a pilot’s reflex, Cooper asked for details.

“There was a fire.”

Cooper knew what that meant. The combination of the 100% oxygen atmosphere and all the flammable materials aboard would have done them in quickly. He later learned that it couldn’t have been more than half a minute. NASA never released the audio of communications between the Apollo 1 spacecraft and Launch Control to the public. Cooper had heard it once and it was awful to hear his three fellow astronauts trying to escape the burning spacecraft. Changes were made though Cooper didn’t see the sense of including only water-based fire extinguishers and not Halon, which made combustion impossible.

The Apollo project was delayed while necessary adjustments were made. The American public and Congress questioned the wisdom of spending so much money, and now three lives, on a space race when there were problems at home. For a while, it looked like America would not make it to the Moon by the end of the decade. But NASA picked up the pieces and moved on.

Leaving NASA

Once the Apollo program got back on track, NASA made a few unmanned test flights and then got back into the manned space business with Apollo 7. The crew was Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele and Walter Cunningham. They successfully tested the command module’s maneuvering system. Wally Schirra retired from NASA soon afterwards.

Once the Apollo program got back on track, NASA made a few unmanned test flights and then got back into the manned space business with Apollo 7. The crew was Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele and Walter Cunningham. They successfully tested the command module’s maneuvering system. Wally Schirra retired from NASA soon afterwards.

Now, the only Mercury astronauts remaining with NASA were Gordon Cooper, Deke Slayton and Alan Shepard. Deke Slayton had been yanked from his Mercury flight and grounded after NASA physicians discovered an irregular heartbeat during a centrifuge run. Alan Shepard had been grounded with an ear condition that gave him debilitating dizzy spells. Both had taken desk jobs at NASA and were in charge of crew assignments, and they both hoped to beat their medical conditions to become active astronauts again. In the competitive world of the astronauts, this would mean trouble for Gordon Cooper.

The trouble wasn’t entirely Slayton’s and Shepard’s fault. It started in Congress. A Senator from Wisconsin named William Proxmire was an opponent of the space program and practically in charge of the Budget and Space Committees. NASA had planned for a mission to Mars in the early 1980s that Cooper thought he had a good chance to command, but Proxmire was instrumental in killing both the Mars mission and the Saturn rocket program. No more Saturns meant that the Apollo program would end with Apollo 17. Cooper was still angry about it at the time he wrote his autobiography and thought William Proxmire deserved one of his own Golden Fleece Awards.

Cooper had served on the backup crew for both Gemini 12 and Apollo 10 and felt that he deserved a chance at prime crew for one of the Moon landings. He went to see Slayton and Shepard about it, only to get a cool reaction from Ice Commander Shepard: “We’re deciding on crew assignments now, Gordo.” They again handed him backup duties for Apollo 13. They would claim that Cooper never seemed as devoted to the work involved with being an astronaut, but he didn’t buy it and blamed astro-politics. Cooper tried appealing to Bob Gilruth, to no avail. He quit in frustration and it would be many years before he would forgive either of them. The Air Force offered him a promotion and a plump command position but, when told that he wouldn’t be allowed to fly single-seat fighters, he chose to retire as a full-bird colonel with 23 years of service.

After NASA

Cooper soon found a job at Disney, as the vice president of research and development. He let word get around that he had an open-door policy. Even if someone had no official standing with Disney, they could come in if they had an idea they thought was worth developing, but didn’t have the resources to do it themselves and couldn’t find someone to back them. If Cooper thought it looked promising, and not all of them were, he bought it and researched it to see if Disney could make it practical. It didn’t always work out. Ideas like a new method for projecting 3-D movies without requiring 3-D glasses fell by the wayside because theater owners didn’t want to make the investment. Cooper disliked that many excellent innovations were either never implemented or were slow to become widespread because nobody wanted to spend the money.

He remained active in several technological and construction companies, including Craftech Corporation and Aerofoil Systems, Inc. He continued to fly as often as he could and would have gone back into space if offered a chance to travel to the Moon or Mars. In fact, he claimed that if a UFO landed and offered him a ride, he’d take it in a heartbeat. He died on October 4, 2004.

More About Gordon Cooper

Gordon Cooper Collectibles