John Herschel Glenn

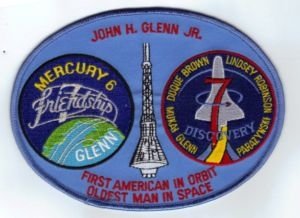

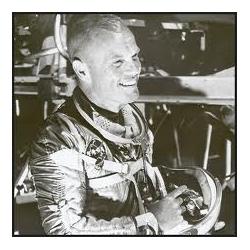

John Glenn was the first American to orbit Earth and also holds the record for the oldest astronaut to go into space. He was one of the original American astronauts known as the Mercury Seven, a group of aviators and test pilots chosen from across the Navy, Marines and Air Force who became instant heroes and celebrities. He has also served 24 years as a U.S. Senator.

John Glenn was the first American to orbit Earth and also holds the record for the oldest astronaut to go into space. He was one of the original American astronauts known as the Mercury Seven, a group of aviators and test pilots chosen from across the Navy, Marines and Air Force who became instant heroes and celebrities. He has also served 24 years as a U.S. Senator.The John Glenn Story

Childhood in New Concord

Like the rest of the Mercury astronauts, John Glenn was a small-town boy. His earliest memories included Decoration Day (later Memorial Day) in 1920s New Concord, OH. His father, a bugler who had also delivered artillery shells to the front in World War 1, would march in the parade and play taps. He taught his son the military bugle calls and, one year, invited him to help play taps. Glenn’s father was his hero and he was thrilled.

He would later wonder if Norman Rockwell had ever visited New Concord. The surrounding countryside was perfect for climbing trees and exploring wide-open fields with his playmates. He lived in a house big enough for his parents to rent rooms out to boarders. He was an only child until he was five, when his parents adopted a girl named Jean.

He doesn’t seem to have caused much actual mischief except for a few isolated incidents. One time, he ventured out to a creek near his house with some friends even though he didn’t yet know how to swim. He didn’t answer his mother’s calls and she switched him for it. She would later admit that she was afraid he had drowned. Another time, he got some scratches on the dining room table while working on a model airplane and his mother made him sand them out.

He got his first chance to fly when he was eight years old. His father was a plumber and Glenn was riding along to a plumbing job when they passed a WACO. They stopped and his father asked if he wanted a ride. Glenn loved it. From then on, whenever the frequent health scares forced him inside, he would entertain himself by building and flying model airplanes. He dreamed of learning how to fly but, due to the Depression, wouldn’t get the chance until he was in college.

A bicycle was a more reasonable goal and Glenn found ways to earn money to buy one. He sold rhubarb out of his family’s garden and washed cars. One finicky customer taught him not to cut corners with any job. While on a business trip with his father, he spotted a good deal on a bike and put a lot of miles on it. He continued to earn money by delivering newspapers on his bicycle.

One of the highlights of his childhood was a club he and some of his peers formed, called the Ohio Rangers. It was modeled after the Boy Scouts and they found an advisor who had an old copy of the Boy Scout handbook. It wasn’t long before they had their own camp, where they spent most of the summer of 1933. A thunderstorm destroyed it and they moved to a log cabin. Club meetings became sporadic and then stopped altogether when the members reached adolescence and moved on to other matters.

The Glenns worried about losing their house to foreclosure but were otherwise lucky during the Depression. His father was having trouble finding paying plumbing jobs, though farmers would sometimes trade beef or pork for work. They had their own vegetable garden and Glenn hunted for rabbits with his two hounds. They were also beneficiaries of Roosevelt’s New Deal. They were able to renegotiate their mortgage using a government program. When the Works Progress Administration came to New Concord to upgrade the water system, his father signed on as a plumber and later became a foreman. More farmers were having electricity installed on their farms for the first time, thanks to the Rural Electrification Administration, and this indirectly led to more jobs for his father to install indoor plumbing. Glenn would remember these as examples of how the government could help people in a crisis.

Annie

Inevitably, John Glenn and his peers became teenagers and began to pair off with the girls in their community. Glenn spent a lot of time with a young lady named Anna Margaret Castor. They had known each other since their toddler years, when their parents became part of a social club called the Twice Fives Club. She was a beautiful girl who had a terrible stutter and Glenn became her champion, chasing off children who taunted her because of it.

Inevitably, John Glenn and his peers became teenagers and began to pair off with the girls in their community. Glenn spent a lot of time with a young lady named Anna Margaret Castor. They had known each other since their toddler years, when their parents became part of a social club called the Twice Fives Club. She was a beautiful girl who had a terrible stutter and Glenn became her champion, chasing off children who taunted her because of it.

New Concord was a welcome environment for her. She never realized that her stutter made her different until she was in sixth grade, when she was called on to read in front of the class for the first time. The boys laughed at her. Otherwise, she was an excellent student.

Both John and Annie Glenn had an interest in music. Annie’s stutter would mysteriously disappear when she sang and she also played piano, organ and trombone. John Glenn played the trumpet. They both joined the high school orchestra, the town band and the glee club. Although her dream was to be a teacher, she majored in music at Muskingum College.

By the time they finished high school, they were talking about marriage but put it off until World War II prompted Glenn to join the military. He spent $125 on an engagement ring.

Muskingum College

Muskingum was the only college that John Glenn seriously considered attending. It was close to home and he was able to get a work scholarship to help with tuition. Inspired by a local chemist named Julian White, who had let him help out in his lab, Glenn planned to major in chemistry. It was not easy. He needed a higher level of math than he had taken in high school to take organic chemistry and he found the course work difficult.

At the beginning of 1941, soon after Christmas break, Glenn noticed a posting on the physics bulletin board that would change his life. The U.S. Department of Commerce was looking for qualified students to train as pilots. The only condition was that they had to be available for military service as needed. Applying was an easy decision to make. The difficult part was convincing his parents, who worried about the risk. A friend name Doc Martin had a talk with his parents and explained that flying would bring numerous opportunities over the next few years. Glenn was accepted along with four other Muskingum students and began lessons in aerodynamics, the atmosphere, and airplane controls.

Their flight instructor was a young man named Wallace Spotts, a college dropout who was devoted to flying. They were his first class. They practiced in a simple Taylorcraft two or three afternoons a week. Glenn was soloing by early May and received his private pilot’s license on June 26, 1941. He celebrated by taking his father for a flight and barely missed a row of trees during takeoff. His father ribbed him about it.

He was in his junior year when news of the Pearl Harbor attack broke. He was on his way to a recital in which Annie would be performing when he heard about it on the radio. Japan’s audacity astonished him and it was all he could do to sit still for her performance of Finlandia. They both understood it meant he couldn’t put off joining the military any longer. He chose the Navy.

Navy Training

Glenn took a train to Iowa City and a new training facility called the Naval Aviation Pre-Flight School. Highlights included a highly competitive athletic program put together by college football coach Bernie Bierman and lessons in navigation, aerodynamics, engines, Navy regulations and the Articles of War. He missed Annie terribly but had few other complaints. When he finished preflight training, he took a few days’ leave to see her before heading to Kansas for more classroom work.

Olathe Base was so new that the only things that were ready for the students were the planes. The barracks weren’t complete and it didn’t even have a system for playing military calls. Somebody found out that Glenn had learned them from his father and handed him a trumpet. Training kept all the students busy but he wrote to Annie whenever he could find a few minutes.

After three months at Olathe, he was assigned to the Naval Air Training Center in Corpus Christi, Texas. He learned instrument flying in OS2U Kingfishers and Vultee Valiant “Vibrators”. He also became more attracted to the Marine Corps, which seemed to have a little something extra he couldn’t quite put his finger on. He attended a talk by a Marine captain with a fellow trainee named Tom Miller. The Marine spoke of the fierce fighting in the Pacific and how the Marines were often in the thick of battles like Guadalcanal. Upon finding out that they were in the top ten percent of their class, both Glenn and Miller applied for Marine commissions and were accepted.

Glenn completed his advanced training in March 1943 and married Annie soon after. His father gave him a 1934 Chevy coup as a wedding present and they drove it out to his new post in Cherry Point, North Carolina. They found an apartment not far from Atlantic Beach so, not long after moving in, they spent a day out on the beach and got ferocious sunburns. Glenn got in some more classroom training in night vision, combat tactics, Marine history and other subjects but a shortage of airplanes made actual flying difficult. In true military fashion, the Marines hit on the perfect solution and sent Glenn and others from the East Coast to sunny California. Glenn bought a new set of tires for the trip and saw many of the highlights of America during the trip west. He reported for duty at the base in Kearney Mesa, not far from San Diego.

Whistling Death

El Centro

While in San Diego, Glenn and Tom Miller managed to get assigned to a squadron due to get some Chance Vought Corsairs, though it was a near thing when Glenn made the mistake of ignoring the chain of command. Then, he and Annie had to move again when the entire squadron was reassigned to El Centro on the Mexican border. They arrived on July 4, 1943, while El Centro was experiencing a record-breaking heat wave. Eventually, they lucked out and found an apartment with a desert cooler, which evaporated water to cool the air. He learned how to fly the F4F Wildcat and got quite a bit of gunnery practice in. A fierce competition sprang up between the pilots to see who could hit the most practice targets.

While in San Diego, Glenn and Tom Miller managed to get assigned to a squadron due to get some Chance Vought Corsairs, though it was a near thing when Glenn made the mistake of ignoring the chain of command. Then, he and Annie had to move again when the entire squadron was reassigned to El Centro on the Mexican border. They arrived on July 4, 1943, while El Centro was experiencing a record-breaking heat wave. Eventually, they lucked out and found an apartment with a desert cooler, which evaporated water to cool the air. He learned how to fly the F4F Wildcat and got quite a bit of gunnery practice in. A fierce competition sprang up between the pilots to see who could hit the most practice targets.

In October, the squadron got the new version of the Corsair and Charles Lindbergh came out to give a presentation on recent changes made to make landing less problematic. Glenn was one of the first to get a chance to try out the new version and enjoyed it. Soon after, he was chatting with his squadron commander, Major Pete Haines, when he finally got his answer to what made the Marines so different from the Navy. Haines explained, “Marine training makes each Marine more afraid of letting his buddies down than he is of getting hurt himself. And that wins battles.” Glenn would never forget that.

Marshall Islands

Glenn’s squadron was slated to leave for their assignment to Marshall Islands on February 5, 1944. Saying goodbye to Annie, he remembered a line from an old story: “I’m just going to the corner store for a pack of gum.” Annie answered, “Don’t be long.” That exchange became a tradition whenever they had to say goodbye.

Their first stop was Hawaii. His trip in the Santa Monica was enough to convince him that he would have made a poor sailor. After a miserable six days, he was happy to see the Hawaiian shore. Due to a delay, he was able to visit Waikiki Beach and found a hula outfit for Annie. Then, their orders changed and they were sent to Midway Islands. They got some entertainment by watching albatrosses wipe out on the beach and listening to the Japanese propaganda program Tokyo Rose, which seemed to have eerily current information on what was happening at Midway and kept promising that the Japanese would overrun the base in the near future. The entire squadron felt that they were certainly welcome to try.

At the end of June, they were finally on their way to Marshall Island and the war. His first combat assignment was flak suppression over Taroa Island. He witnessed his first casualty in combat, when a member of his division named Monty Goodman was shot down. They found the place where Goodman’s plane had hit the water but never found him. It hit Glenn hard when he saw Goodman’s empty parachute bin and, as the division leader and Goodman’s friend, he felt obligated to write to the parents.

The Japanese learned to call the Corsairs “Whistling Death” from the way their wings whistled when they dived. Glenn’s squadron would alternate between flak suppression and bombing runs, and Charles Lindbergh even joined them for a couple of missions. Glenn loved flying so much that Haines suggested that they apply for a regular commission, since he was officially part of the Marine reserves. Glenn wasn’t sure if he wanted to make a career of the Marines but put his name in anyway.

The Allies continued to push the Japanese back though the fighting was fierce. Glenn even found a human skull that the flight surgeon said was probably Japanese, since they preferred to fight to the death. He eventually rotated back to the States and took leave to see Annie before being assigned to the Naval Air Test Center at Patuxent River.

After the War

Glenn was reassigned to Cherry Point, where he joined another Corsair squadron. Annie, then pregnant with their first child, set up housekeeping nearby. The war ended not long afterwards, leaving much of the military in limbo. Glenn’s Marine commission had not yet come through. His father suggested that he take over the plumbing business and New Concord’s dentist suggested that he take up dentistry and join his practice. Glenn wanted to keep his options open and even toyed with the idea of buying some surplus military transports to start a shipping company. Then, he received word that his commission had been granted and talked it over with his wife. She was supportive and he remained with the Marines.

Their son, John David, was born while they were at Cherry Point but they didn’t remain long. Glenn was reassigned to El Toro and a squadron called the “Death Rattlers” in March 1946. Many mechanics had left the military after the war, leaving the pilots with no choice but to maintain the planes themselves. They flew in lots of shows, which quickly became boring for Glenn. When he learned of a chance at a short tour in China, he volunteered.

China was in the middle of a civil war and the Communists were trouncing the Nationalists. It was not a safe place to be part of the U.S. military. The Communists perceived them as supporting the Nationalists, even though nobody was particularly impressed by the Nationalists and the U.S. military was officially there to provide security for peace efforts. They had to deal with routine threats from the Communists and a few mysterious deaths that encouraged them to travel in armed pairs. The peace initiative eventually had to evacuate from Peiping to Tientsin with Glenn and the other military pilots flying patrol overhead. His squadron was preparing to move to Guam when he received some welcome news. Annie had given birth to a baby girl named Carolyn Ann.

As weeks passed in Guam, it became obvious that Glenn had been duped. The “short” tour was stretching out into a long one, briefly interrupted by a scare when he heard Annie had been hospitalized with an infection. He took some emergency leave and flew home, finding Annie recuperating in her parents’ house. He was happy to see his daughter for the first time but had to go back too soon. Eventually, the Marines got permission to build Quonset huts for their families and Annie came over with their children. Glenn had been overseas for eighteen months when they arrived. Three months later, Glenn received orders to return to the States and they traveled home on the Santa Monica. They pulled into San Francisco Bay in December 1948.

After a few months in Corpus Christi, he volunteered for a program in which the Navy and Air Force exchanged instructors. He flew his first jets at Williams Air Force Base in Arizona. Then, the Korean War began in June 1950. After a frustrating wait and a course at the Amphibious Warfare School, Glenn was sent to Korea in October 1952.

MiG Mad Marine

Most Americans were not thrilled with the way the Korean War was being handled, and that included Glenn’s parents and parents-in-law. Casualties were piling up and cease-fire talks went nowhere. Dwight Eisenhower was elected president partly in the hope that he could bring the war to an end. Still, they were supportive of his decision to go.

Most Americans were not thrilled with the way the Korean War was being handled, and that included Glenn’s parents and parents-in-law. Casualties were piling up and cease-fire talks went nowhere. Dwight Eisenhower was elected president partly in the hope that he could bring the war to an end. Still, they were supportive of his decision to go.

Glenn reported to K-3, a Marine base in southeastern South Korea, and the thing that seemed to impress him most was the poverty of the local Koreans. The locals would walk or ride bicycles everywhere. Nothing was wasted, not even the garbage from the base. People would come out and search through it for anything edible until a near-riot forced the base to come up with a better system.

Glenn also met baseball star Ted Williams, who had been playing with the Red Sox but was a member of the reserves and got called up six days into the season. It wasn’t long before his fellow squad members tagged him with the nickname “Bush” to tease him and he developed a liking for the fudge that Glenn’s sister-in-law Jean sent over in care packages. Williams proved to be as attentive to his flying as he was to his hitting.

Glenn’s old friend Tom Miller was also in South Korea, stationed at the K-6 base, and he flew down to meet up. North Korean anti-aircraft fire was nastier than Japan’s had been and Miller advised Glenn not to go after any guns aimed at him, because there would inevitably be several others that he might not see. A few weeks later, Glenn was making a bombing run when he noticed an enemy anti-aircraft gun. He finished dropping his bombs, and then ignored Miller’s advice and went after it. He was pulling away when another anti-aircraft gun hit his plane. He was lucky to make it back to base and he discovered that the flak had put a huge hole in his plane’s tail. He told Miller all about it the next time they met. He got hit again about a week later, putting a hole in his wing. He wasn’t the only one to have a close call but his squadron dubbed him “Old Magnet Ass” after that.

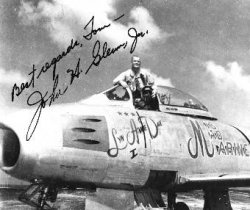

He applied for an exchange program with the Air Force and was approved in spring of 1953. This gave him a chance to fly F-86 Sabres and perhaps fight some MiGs that the North Koreans had acquired from Russia. He was assigned to a squadron based at K-13, just south of Seoul. The Air Force pilots had a custom of naming their planes, so Glenn had “Lynn, Annie, Dave” painted on his, with their initials painted in large letters. His first few missions with his new squadron were uneventful. He griped so much about not seeing any MiGs that someone painted “MiG Mad Marine” on his plane. His first impulse was to have it removed, but then, he decided “MiG Mad Marine” was exactly right. It may have been a good omen, because he did end up shooting down three MiGs before the war ended.

After the official end of the war, Glenn was reassigned back to K-3, where he became Tom Miller’s assistant. The job included helping receive the American prisoners as they were released. The assignment lasted through December and, when he wrote home, he told his children to put some snow down Annie’s back for him. He hunted pheasants with some friends and they hosted a Christmas party for the local children. Watching the children play pilot in their planes made being away from home a little easier and Glenn had a belated Christmas with his family when he made it back.

F-86 Sabre vs MiG-15

The best of Soviet fighter jets meet the best of American fighter jets. Which one is better? During the fight for supremacy over the skies of the Korean peninsula, a stretch of airspace became known as MiG Alley.

Test Pilot

Glenn had to give some thought to the next stage in his career. Pilots rarely made into the highest ranks of the Marines, so he decided to focus on his flying. In the absence of war, becoming a test pilot sounded promising but Annie wasn’t thrilled with the idea. Being a test pilot meant finding the flaws in brand-new fighter plane models that designers and engineers could not always anticipate and the work was not much safer than being a combat pilot. She eventually accepted the idea and he attended the test pilot school at Patuxent River. He had to request a waiver for the degree requirement when he applied and it was not the last time his lack of a degree would almost cost him. The required algebra and trigonometry came back to him easily but calculus was a new subject that he wrestled with. He learned how to fly tests in familiar planes and write flight reports. It was challenging, but he graduated in July 1954 and received an assignment for armament tests.

Glenn received an example of how risky being a test pilot could be almost immediately. His first plane was a modified version of the F-86 Sabre called the FJ-3 Fury. He flew the plane to forty-four thousand feet to test the four twenty-millimeter cannons. He fired and the canopy seal blew. The oxygen regulator was also damaged and he activated the backup oxygen system. The backup was also malfunctioning and the first clue he had came when his vision started to fade. Fortunately, he had a second backup in the form of a small bottle that could supply oxygen through a rubber tube. It relied on him being able to reach it in time and he squeezed the little green ball to activate it. He made it back to base and saved the little ball.

Tests with the F7U Cutlass revealed some problems with burnout at higher altitudes, and then a cannon muzzle flew off during one of Glenn’s firing tests. It turned out that repeated firing had weakened the metal. The F8U Crusader gave him his next real scare when he fired the guns and the plane promptly rolled to the right. Glenn got it back under control but could only keep it that way by keeping pressure on the stick. When he landed, mechanics promptly spotted the problem and came running. He had lost nineteen square feet of the right wing. The gunfire had created a resonance frequency that equalled the distance from the gun to the wingtip. As a result, the wing had snapped like a whip and the end came clean off. They were able to fix the problem and, while the modified version of the Crusader started going out to regular service, Glenn continued to help improve it.

In November 1956, he was transferred to the Navy Department’s Bureau of Aeronautics as a project officer. This meant he would be working in Washington but, rather than uproot his family in the middle of a school year, he decided to commute. The work taught him how expensive the modifications suggested by test pilots could be and he would often joke to engineers employed by the contractors that they ought to just live off the changes. He also got the chance to watch the Senate during their debates.

He remained convinced that the Crusader could be a good combat plane but others questioned whether it had received enough testing to make certain there would be no more problems at high altitudes. Glenn decided to come up with the ultimate test, one that was also sure to get people’s attention. He would try to break the current transcontinental speed record in a Crusader.

John Glenn’s Transcontinental Flight

Project Bullet

He spent months convincing the Navy bureaucracy that the Crusader could beat the record time then held by the Air Force. Some of the admirals and generals were a little envious because there were pilots in their ranks as well. Finally, in the spring of 1957, they agreed on the condition that he have a backup pilot who would fly a second plane. Navy Lieutenant Commander Charles F. Demmler came on board. The date was set for July 16, 1957.

He spent months convincing the Navy bureaucracy that the Crusader could beat the record time then held by the Air Force. Some of the admirals and generals were a little envious because there were pilots in their ranks as well. Finally, in the spring of 1957, they agreed on the condition that he have a backup pilot who would fly a second plane. Navy Lieutenant Commander Charles F. Demmler came on board. The date was set for July 16, 1957.

They would have to refuel in mid-air three times. He would have preferred to have some jet tankers for the job, but the Air Force had the only ones at the time and they refused his request. Glenn suspected inter-service rivalry behind the bureaucratic language. That meant he would have to settle for the Navy’s twin-prop AJ refuelers, which would slow him down. The two pilots spent a lot of time practising the manuevers needed for rendezvous and refueling and joking about which of them would cross the finish line first. Glenn and Demmler also made certain to get “sporting licenses” from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale to make the record official.

He took off from Los Alamitos Naval Air Station in California at 6:04 am and climbed quickly through the slight overcast and got as high as Mach 1.48. Dimmler would take off half an hour later but had problems with refueling and had to land. His first refueling manuever was in New Mexico, just west of Albuquerque. “Check under the hood?” joked the refuel pilot. Glenn quipped back, “Don’t bother. I’m sort of in a hurry this morning.” “Come and see us again. I’ll mail your Green Stamps in the morning.” The refueling had gone twenty seconds longer than planned but Glenn hoped to make up for lost time. His second refuel over Emporia, Kansas went well but difficulties with the third caused the flow to stop prematurely. With nothing he could do about it, he pulled away with a thousand pounds less fuel than he had planned on.

His flight plan took him close to New Concord at Mach 1.4, causing some impressive sonic booms. He had told his relatives back home about his planned run and they had turned out to watch him pass overhead. One neighbor kid heard the sonic booms and thought Glenn had dropped a bomb. The booms did cause some damage along his flight route, such as broken windows and a collapsed ceiling. He reached Floyd Bennett Field in Long Island and streaked past the official finish line with three hundred pounds of fuel to spare. He had broken the record by 21 minutes with an average speed of Mach 1.1. Rear Admiral Thurston B. Clark was there to meet him, along with a gaggle of reporters and Glenn’s family. If he was prone to develop an ego over it, though, all he had to do was read the profile that the New York Times ran: “At 36, Major Glenn is reaching the practical age limit for piloting complicated pieces of machinery through the air.” The Times clearly had no idea how he would laugh at such blatant age discrimination decades later.

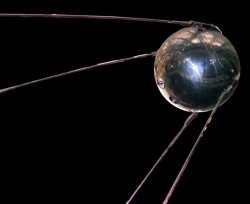

The Marines couldn’t resist the publicity and sent Glenn on tour. While still in New York for some appearances and news conferences, he met a woman associated with the game show Name That Tune. She invited him to come on the show and the Marines gave him the go-ahead. He was paired with a freckle-faced ten-year-old named Eddie Hodges, who went on to join the original cast of the Broadway musical The Music Man. They split a $25,000 prize and Glenn’s share went to start a college fund for his children. It wouldn’t be long, though, before his record flight was overshadowed by a Russian satellite called Sputnik.

“A Soviet Moon”

Sputnik caught America completely flat-footed and the Russian president laughed about how America was now under “a Soviet moon.” The sound of its radio signals coming from orbit made it obvious that space was the new high ground. American forces raced to put a rocket of its own into space but the first attempt, a Vanguard, exploded on the launchpad. This elicited howls of “Kaputnik” and “Stayputnik” from the media.

Glenn quickly decided he wanted to be a part of the American space effort and jumped at a chance for a post with NASA’s predecessor, NACA. They were working on a rocket plane called X-15 and exploring other possibilities and were looking for test pilots to help with simulations. While working with NACA, Glenn had his first encounter with a centrifuge. Military pilots routinely experienced up to 9 Gs while flying but the centrifuge was a different story. The centrifuge had him experiencing up to 8 Gs in a variety of positions, including supine. He was hooked up to sensors to monitor his vital signs and began to sympathize with the dog the Russians sent up in Sputnik II. He also sat in on meetings held to discuss the shape of the space capsule. President Eisenhower was noncommittal about future space plans until he signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which created NASA as a civilian agency, and NASA inherited NACA’s resources. Perhaps the chance to witness early space efforts gave Glenn a small edge when NASA began looking for its first astronaut recruits.

He was certainly determined. He promptly started a diet and exercise program to lose weight. His friend Tom Miller would claim that he either strapped encyclopaedias to his head every night to get shorter, or slouched to make the height limit. Glenn denied that he had done either. His lack of a degree almost cost him his chance, but another friend, Jack Dill, went to bat for him and convinced the selection board that Glenn had enough classroom hours to equal a master’s degree. In the meantime, Glenn transferred all of his credits to Muskingum but didn’t have the residency requirement to get a degree.

He went through the exhaustive testing at Lovelace Clinic and Wright-Patterson with the candidates who hadn’t already been eliminated or backed out. They included getting dunked in cold water and having water sprayed into their ears. At least one candidate got fed up and stormed out. When they put Glenn in the isolation chamber, he found a notebook and pencil by feel and tried writing down his thoughts. Glenn would later quip to the reporters at the press conference announcing the Mercury astronauts’ selection, “Which one would you hate the most?”

Annie worried about the danger but Glenn assured her that NASA would make certain it was as safe as possible before sending a man up. She asked him how to spell “astronaut,” a brand-new word at the time. Then, she laughed at him. “Are you sure they shouldn’t drop the second A?” He made the final cut and was informed on April 6, which was his sixteenth wedding anniversary.

The Press Conference

Change of Lifestyle

None of the astronauts were really prepared for the media attention. Reporters seemed to delight in ambushing them and their families. It was rough on Annie to have to answer questions with her stutter and Glenn went to NASA’s information officer, Walt Bonney, to see what could be done. They came up with the idea that they could sell the astronauts’ personal stories to the highest bidder. A lawyer named Leo D’Orsey volunteered to act as their agent and worked out a deal with Life magazine. Glenn added his share of the money to his children’s college fund.

None of the astronauts were really prepared for the media attention. Reporters seemed to delight in ambushing them and their families. It was rough on Annie to have to answer questions with her stutter and Glenn went to NASA’s information officer, Walt Bonney, to see what could be done. They came up with the idea that they could sell the astronauts’ personal stories to the highest bidder. A lawyer named Leo D’Orsey volunteered to act as their agent and worked out a deal with Life magazine. Glenn added his share of the money to his children’s college fund.

Glenn decided not to uproot his family and moved into bachelor officer quarters at Langley Air Force Base. While most of the astronauts tried to outdo each other with new cars, he bought an NSU Prinz that got 45 miles per gallon. He took some kidding for it but saved on gas when he commuted back to Arlington on the weekends.

Training began in early May and the astronauts went out to Cape Canaveral to watch the launch of one of the Atlas rockets. It exploded about a minute into the flight, which didn’t reassure any of them very much. Later that month, they launched and retrieved two monkeys named Able and Baker. Able died on the operating table but Miss Baker would find a home at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

They began centrifuge runs at Wright-Patterson and decided that 16 Gs was the practical limit for maintaining consciousness. It helped determine their ability to reach controls while dealing with the pressures of lift-off. They also tried “tumble runs,” in which they would switch from positive Gs to negative Gs to simulate a space capsule that tumbled during an emergency ejection. One person came out of a tumble run coughing uncontrollably, putting limits on that. In the meantime, the Russians launched Luna 2, which crash-landed on the moon, in September 1959. They crowed about their latest victory, sending the first man-made object to the moon. In December, NASA launched another monkey. Some of the astronauts would come to hate the sight of monkeys and chimps and the jealousy and jokes they got from colleagues at Edwards Air Force Base would not help.

Survival training came when NASA officials realized that an unplanned re-entry could force an astronaut to fend for himself for a few days. Glenn would get himself into serious trouble during desert training. He decided to go without water for a day just to see what happened and, when they checked on him, he could barely move. He recuperated nicely and learned his lesson.

NASA also wanted their input on the spacecraft they were developing. The seven astronauts often held meetings to catch up on each other’s work, make decisions, and settle disputes so they could take their recommendations to NASA officials as a team. One thing they agreed on was the need for a window on the spacecraft. If the automated systems failed, they would need to be able to orient themselves by sight. The engineers understood the problem but adding a window to the spacecraft proved tricky.

To make their work easier, they divided up the areas of development and John Glenn was assigned cockpit layout and instrumentation, spacecraft controls, and simulation. They traveled a lot to the various contractors to check on progress. Glenn enjoyed meeting with the workers who were building their spacecraft and would often stop to shake hands and chat.

They visited the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama and met the team of German engineers led by Wernher von Braun, whose development of rockets led to the Redstone and Atlas used to launch the Mercury spacecraft. Glenn was impressed by von Braun’s wide field of interests, which ranged from the sciences to religion and government.

As their duties took them to Cape Canaveral more often, the astronauts typically stayed at a local Holiday Inn, where they made friends with hotel owner Henri Landwirth. Landwirth had to get used to astronauts letting off steam in his hotel but soon learned to give as good as he got. One night, Glenn realized there were no towels in his hotel room and went to the front desk to ask for some. The next time he checked in, there were towels stacked four feet deep on every available surface of the room. Landwirth innocently peeked around the corner and asked, “Do you have enough towels, sir?” They would eventually become business partners and open a few Holiday Inns in the Disney World area.

Some of the astronauts couldn’t seem to get used to the idea that they were being put on a pedestal. The fact that they were celebrities meant they would run into temptations when dealing with the general public and, inevitably, one of them got caught in a compromising situation by a reporter and photographer. Glenn found out about it and used all his powers of persuasion to convince the newspaper not to run the story. Furious, he called a meeting and read the riot act to his fellow astronauts. Most of them interpreted it as interfering with their private lives but he didn’t think it would affect his career as an astronaut much. Not long afterwards, Bob Gilruth, director of the Manned Space Center, met with the astronauts and asked for a peer review.

Backup

Every single Mercury astronaut hoped to be first to go into space. At the news conference announcing their selection, somebody had asked who was ready to go into space right then. All of them raised hands and John Glenn and Wally Schirra raised both their hands. Glenn felt he had a good chance of being first and was disappointed when he learned that he would be backup for the two suborbital flights, which went to Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom. He felt that it was unfair that the peer review would be a factor and let Bob Gilruth know in a strongly worded letter.

Making it worse, NASA decided to pretend that they had simply narrowed the selection down to Shepard, Grissom and Glenn, who became known as the “Gold Team” to NASA staff and “The First Three” to the press. They had to go along with it even though Shepard did make some sarcastic remarks to the press: “I would hope they would inform me the day before the flight.” Glenn sympathized with Slayton, Schirra, Cooper and Carpenter, who slid into the background and became the forgotten four.

They still had a job to do and pulled together as a team. As Shepard’s backup, Glenn worked closely with him and attended meetings on his behalf whenever he was busy with training. Psychiatrists followed them around, concerned that Shepard might not want to come back once he reached space. Shepard probably thought they were being ridiculous but Glenn didn’t mind so much. Space flight was a new business and nobody was quite sure what would happen.

The delays were just as frustrating. NASA decided to send up chimps first. Ham went first in a Mercury-Redstone, but problems with the flight led to the decision to send another. Some scientists outside of NASA wanted to send a dozen. Shepard began talking about “a chimp barbecue” and the rest of the astronauts agreed. They went to Gilruth and flight director Christopher Kraft, who arranged a meeting with the scientists. They managed to convince the scientists that it was unnecessary to have so many chimp flights. It would ultimately lead to Shepard losing out on the chance to be the first man in space. The Russians beat him out and he had to settle for being the first American. Glenn managed to lighten up the situation by placing a sign saying “No Handball Playing In This Area” in the cockpit of his space capsule on launch day. Shepard loved playing handball and got a good laugh out of it.

Both suborbital flights were a success despite Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7 sinking. NASA had planned for several suborbital flights, but the Russians ramped up the pressure by putting a second man in orbit. NASA shifted tactics and decided to go with an orbital flight. John Glenn drew the assignment despite some more media harping about his age. He had just turned forty.

Friendship 7

First Orbital Flight

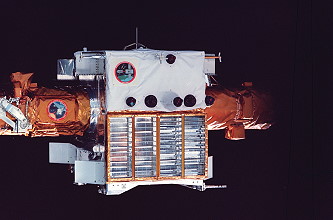

To keep his children involved, Glenn asked them to help name his space capsule. They came up with several candidates, including Columbia, Hope and Harmony. The favorite was Friendship, so Glenn’s spacecraft became the Friendship 7. He asked the painter to use script letters on the spacecraft.

To keep his children involved, Glenn asked them to help name his space capsule. They came up with several candidates, including Columbia, Hope and Harmony. The favorite was Friendship, so Glenn’s spacecraft became the Friendship 7. He asked the painter to use script letters on the spacecraft.

He jumped right into the business of preparing for the flight and his backup, Scott Carpenter, became as involved with helping Glenn as Glenn had been with Shepard’s. Glenn trusted him to take care of the details. They even relaxed together, riding around in Carpenter’s Shelby Cobra, dining at a local Polynesian restaurant and singing together whenever Carpenter brought out his guitar.

Glenn fought to have a camera on board, believing it would be valuable if people on the ground could see what he saw. He found a $45 Minolta they could adapt for the job. He also came up with a message he could use to introduce himself to less technological societies in the event that he landed in a remote corner of the planet. He thought it came out sounding like “Take me to your leader” but it was better than nothing.

With the flight assignment came an upswing in attention and fan mail. Glenn had to ask reporters to wait outside the church on Sunday mornings. Secretary Nancy Lowe, who had been assigned to the seven from the beginning, helped him with the sackfuls of mail he was now receiving. He moved into crew quarters at Cape Canaveral to cut down on the chance of catching a bug but did have one scare after a dinner with Henri Landwirth. One of Landwirth’s children came down with the mumps and he promptly called Glenn. He woke up with a sore neck a couple of days later but it turned out to be simply strain from moving his head against an inflated space suit. It prompted Glenn to be more careful.

They had been aiming for a December flight but a series of delays pushed the launch date back to January 27th. Glenn got the chance to celebrate Christmas and New Year’s Day with his family and had a talk with his children about the risk. He was the last to feel the tension building around the flight. Even some of the media people were beginning to feel it and ABC, NBC and CBS decided to go with uninterrupted coverage. As one network executive told TV Guide, “That man’s life will be hanging in the balance all the time he’s up there. How can we go back to quiz shows or soap operas while he’s risking his neck for us?”

Launch day came and Glenn was up by two o’clock on a cloudy day. He got ready and rode out to the launch pad. He waited in the spacecraft for six hours but the break in the clouds they had hoped for never came. He returned to Hangar S, changed out of his pressure suit and was promptly bombarded by NASA officials who wanted him to talk to his wife. She was refusing to admit Vice President Johnson into their home. He called her and she said Johnson wanted to bring a gaggle of uninvited reporters into their home and kick out the Life reporter. She wasn’t feeling up for it. He told her he would support her. One of the officials threatened to remove him from his flight and he retorted that if they did, he would hold a press conference to tell everybody why. They never brought it up again.

Psychiatrists around the country were worried that the pressure might be getting to Glenn and wrote in suggesting that he be replaced anyway. NASA had the advice of its own psychiatrists and, if they paid attention to the letters at all, they probably reported that Glenn was still cool and good to go for the flight. Finally, they slated February 20th, 1962 as the launch date.

Flight of Friendship 7

By launch day, the preparation routine was familiar. While they were preparing the pressure suit, Bill Douglas ran a hose through a fish tank to check the air supply. Glenn couldn’t resist having a little fun with him and told him some of the fish had died. Douglas went over to check and realized he had been “Gotcha’d.” Riding out to the launch pad, Glenn got a good look at the Atlas and had to push the time they had watched one blow up out of his mind. With Carpenter’s help, he got into the capsule, he hoped for the final time.

By launch day, the preparation routine was familiar. While they were preparing the pressure suit, Bill Douglas ran a hose through a fish tank to check the air supply. Glenn couldn’t resist having a little fun with him and told him some of the fish had died. Douglas went over to check and realized he had been “Gotcha’d.” Riding out to the launch pad, Glenn got a good look at the Atlas and had to push the time they had watched one blow up out of his mind. With Carpenter’s help, he got into the capsule, he hoped for the final time.

They went through a few delays that were sorted out quickly. He got a chance to talk to his family when Carpenter patched him through on a phone call. Then, the countdown reached zero. Due to a temporary glitch with his earphones, he didn’t hear Carpenter saying, “Godspeed, John Glenn.”

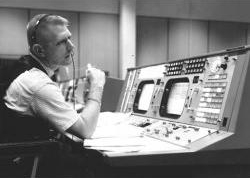

The G-forces built gradually; it took a full three seconds to clear the launch pad but Glenn soon felt the shuddering that meant he was approaching Max Q. This was the part of the flight in which the rocket would go through the worst aerodynamic stress and where a few test flights had resulted in the loss of rockets. He made it through and the ride smoothed out quickly. A minute later, the first-stage booster engines and escape tower fell away. Five minutes into flight, he reached orbit. “Zero G and I feel fine.” The capsule turned around, giving him his first view of Earth. “Oh, that view is tremendous!” He received a “go” for seven orbits although only three were planned.

The flight was on an automated system, though Glenn could override it with either a manual or a fly-by-wire system if he needed to. He reached for his tool pouch and found one of Alan Shepard’s jokes, a toy mouse inspired by comedian Bill Dana’s cowardly astronaut character. Glenn stowed the mouse and reached for the camera to take a few pictures. When he needed both hands, he discovered that he could let go of the camera and it would mostly just float in place.

He had a number of medical experiments to get through. He had to pause occasionally to take his blood pressure. There had been some concern about being able to see and swallow in weightlessness and Glenn found that he could read a vision chart and swallow some applesauce without trouble. He pulled on a bungee cord to raise his heart rate and test his recovery time; it was normal. He took it as proof of how adaptable the human body can be.

Glenn had always liked watching especially outstanding sunsets and sunrises, comparing them to collecting exceptional art pieces only better. His first sunset in space was swift but spectacular and he radioed to Earth, “The sunset was beautiful. I still have a brilliant blue band clear across the horizon. … The sky is absolutely black, completely black. I can see the stars up above.” It gave him the chance to see how many constellations he could identify.

He was watching the sunrise through the periscope when he noticed an unexpected phenomenon. There were sparkling “fireflies” all around his spacecraft. He tried reporting it, but the capcom in Guaymas was only interested in the retro sequence time. The “fireflies” gradually dispersed and they would later learn that they were particles of frozen water from the spacecraft.

The first hints of trouble came during his second orbit, when the capcom relayed an odd message: “Keep your landing bag switch in off position. Landing bag switch in off position. Over.” Glenn made certain it was. “That is affirmative. Landing bag switch is in the center off position.” “You haven’t heard any banging noises or anything of this type at the higher rates [of roll, pitch and yaw]?” “Negative.” They would continue to ask him about the landing bag without telling him why. He figured it out anyway: There was a suspected problem with the heat shield and they didn’t want to worry him. He let NASA officials know exactly what he thought of that when he returned to Earth. He felt that a test pilot should have all the information necessary to do the job, and that meant knowing about any potential problems during the flight.

On Mission Control’s advice, Glenn controlled the spacecraft by fly-by-wire during re-entry. The retro pack burned away during his return; he was literally inside a fireball so intense that he lost radio contact. He wondered if he would feel it if his heat shield did fail. When it diminished, he made contact with Alan Shepard at Cape Canaveral: “That was a real fireball, boy!” He splashed down within six miles of the recovery ship Noa.

Fourth Orbit

The crew of the Noa were so thrilled to have Glenn on board that they made him an honorary crew member and voted him Sailor of the Month. He thanked the crew over the loudspeaker and signed the check over to the ship’s welfare fund. The sun was setting when he recorded his answers to the initial debriefing form. One of the questions was, What would you like to say first? His answer: “What can you say about a day in which you get to see four sunsets?”

The crew of the Noa were so thrilled to have Glenn on board that they made him an honorary crew member and voted him Sailor of the Month. He thanked the crew over the loudspeaker and signed the check over to the ship’s welfare fund. The sun was setting when he recorded his answers to the initial debriefing form. One of the questions was, What would you like to say first? His answer: “What can you say about a day in which you get to see four sunsets?”

He transferred over to the Randolph and then to Grand Turk Island for debriefings and a medical exam. He described the mysterious fireflies and a psychiatrist joked, “What did they say, John?” He later heard that the Russians called it the “Glenn effect.” Scott Carpenter would solve the mystery of what they were on the very next flight but no one could explain the glittering. Glenn found some time to relax and call Annie, who tried to warn him about the building anticipation of his return. There had been excitement over Alan Shepard’s and Gus Grissom’s flights but the tension of the delays and the potentially faulty heat shield combined to create enough drama for a blockbuster movie.

NASA planned to send Friendship 7 on a world tour, which they called the “Fourth Orbit,” and then put it in the Smithsonian. He flew back with Vice President Johnson and landed at Patrick Air Force Base, twenty miles south of Cape Canaveral. The ride to the Cape turned into a surprise parade. People crowded along the sides of the route, waving signs and cheering. Henri Landwirth was the ringleader among the planners and hauled out a huge cake in the shape of a Mercury capsule he had made in honor of the event.

Glenn managed to spend a quiet weekend with his family before flying to Washington with the president on Air Force One. Kennedy’s daughter’s reaction to being introduced to the first American to orbit Earth was a classic: “But where’s the monkey?” Glenn had a speech ready for the joint session of Congress and Kennedy looked it over. He said it looked okay and handed it back to Glenn with the last page on top. President Kennedy was a genuine space cadet who was capable of making his enthusiasm for space exploration infectious. It was a sad day for NASA when he was assassinated.

He attended a short reception at the White House with most of the other astronauts. Gordon Cooper had not yet returned from his post in Australia. The cold, rainy day did not keep people from attending the parade in Glenn’s honor and the sidewalks were packed with thousands of people. The attendees gave him a standing ovation when he entered. He focused on the benefits of exploration in his speech and encouraged Congress to continue to support NASA’s mission.

More parades followed, including one attended by four million people in New York City. Fan mail poured in. Unions praised Glenn for striking a blow against age discrimination. Some people speculated about a potential political future for Glenn, who was ambivalent about it at first. He had his sights on a Gemini or Apollo flight. Some years later, he would hear a rumor that the president considered him a national asset and asked NASA officials to keep him safely on the ground. It soon became obvious that he was being given the run-around whenever he asked about a future flight and retired from NASA. He was soon making plans to run for a Senate seat.

Did you know? John Glenn was actually the third human to orbit Earth. The first two humans were Russian Cosmonauts named Yuri Gagarin and Gherman Titov.

An Abortive Run

Not long after his orbital flight, John Glenn met Bobby Kennedy and began a political discussion that would last for years. Kennedy’s views were a little to the left of Glenn’s but they mostly agreed on many issues. Politics was a very cut-throat business and they agreed that they would be hard pressed to name more than a handful of true friends. Before considering politics as a career, Glenn had never considered himself a member of any party. When he decided to run for the Senate, he chose the Democrats, surprising many of his mostly-Republican astronaut friends. On January 17, 1964, he announced that he would challenge incumbent Stephen Young in the Ohio primary.

He had no money and the Hatch Act prevented him from campaigning directly while he was still a Marine. It seemed like he couldn’t escape the primates who had made the first few space flights. Young made wisecracks about the chimps and monkeys, calling them the true space pioneers.

His campaign came to an abrupt end when he had an accident that nearly killed him. He was staying at an apartment a supporter provided when he tried to adjust the mirror. He lost his grip on the mirror and ducked as it fell toward him. The rug slipped out from under him and he went down hard, knocking himself out for a few seconds. He came to in a pool of blood from cuts on his head and was mostly aware of a terrible pain behind his left ear. Two of his campaign workers heard the crash and called an ambulance. X-rays revealed a concussion and damage to his inner ear that ruined his balance. He would be immobilized by dizzy spells for months. There was no question of continuing his campaign and he announced that he was pulling out of the race from his hospital bed.

To keep his spirits up, he asked his secretary to forward some of the more interesting letters out of his fan mail. Many were from children and included cute lines like “To celebrate your great achievement we were all served cake for lunch today. We’d like for you to go again!” He forwarded one suspicious letter to investigators and turned others into a book titled P.S. I Listened To Your Heart Beat.

By October, he had recovered enough to return to normal activity and, while waiting for his retirement papers to come through, went through a refresher flying course for Marine pilots who had been assigned elsewhere to test himself. He received several lucrative offers for endorsements but didn’t want to become just another salesman. He accepted an offer to become Vice President of corporate development from soda company Royal Crown.

In time, he was promoted to president of Royal Crown International. He also partnered with Henri Landwirth and real estate broker John Quinn to open some highly successful Holiday Inn franchises in the Disney World area. The death of fellow Mercury astronaut Gus Grissom in a launch pad fire rocked Glenn a bit and he attended the funeral. He remained friends with Bobby Kennedy and grieved with the rest of the nation when he was assassinated. Glenn acted as part of the honor guard and helped carry the casket.

He re-entered politics in 1970, when Stephen Young announced his retirement from the Senate and Glenn decided to announce his candidacy. His chief Democratic opponent was solidly anti-Vietnam, while Glenn just questioned the way the war was being handled. The situation was made worse by the Kent State University shootings, in which Ohio National Guardsmen killed four anti-Vietnam protesters. Glenn lost the primary by less than 13,000 votes.

“P.S. I Listened to Your Heart Beat”

This book contains some of the most interesting letters Glenn received from people across America after his Friendship 7 flight.

An Amazing Transformation

1971 started out as a rough year for John Glenn. He lost his mother in January and his wife’s father in March. On Memorial Day, he was riding in the pace car at the Indianapolis 500 when they had a wreck. Nine people were seriously hurt but Glenn was only bruised. He considered it ironic that, after surviving World War II, becoming known as “Old Magnet Ass” in the Korean War, and all the drama involved in his space flight, his biggest risks were riding in a car and shaving. Things gradually improved for him and, two years later, he would have the chance to witness an amazing transformation.

1971 started out as a rough year for John Glenn. He lost his mother in January and his wife’s father in March. On Memorial Day, he was riding in the pace car at the Indianapolis 500 when they had a wreck. Nine people were seriously hurt but Glenn was only bruised. He considered it ironic that, after surviving World War II, becoming known as “Old Magnet Ass” in the Korean War, and all the drama involved in his space flight, his biggest risks were riding in a car and shaving. Things gradually improved for him and, two years later, he would have the chance to witness an amazing transformation.

He and Annie were watching the Today show when Ron Webster made an appearance. He was a psychologist at Hollins College who was doing research into stuttering and had a new theory. His preliminary data showed that stuttering could be a physical, rather than psychological, problem. He believed that the parts of the brain that were hardwired for the sound of speech did not develop properly, interfering with stutterers’ ability to learn how to talk. Webster was using the data to develop a new therapy for stutterers.

Annie was enthusiastic and signed up for an intensive therapy course at Hollins. It involved re-teaching students how to speak, starting with basic sounds and progressing through syllables to entire words. After three weeks’ worth of 11-hour therapy sessions, she was able to call Glenn on the phone, a device she had always avoided, and speak her first clear sentence. They were both thrilled. Annie was finally able to make shopping trips and ride on a bus without having to carry paper and pen to communicate with. She couldn’t resist calling friends all over the country, driving up their phone bill. Her victory became an inspiration for stutterers around the country.

“I Have Held A Job!”

As the end of 1973 approached, the Watergate scandal was developing, Nixon’s attorney general resigned in protest, and Nixon appointed the Senator from Ohio, William Saxbe, to the post. That meant a special election in 1974 and John Glenn went head-to-head with Howard Metzenbaum in the Democratic primary. Their styles were somewhat different. While Metzenbaum hosted $100-a-plate fundraisers, Glenn put on 99-cent corned beef dinners and stood on tabletops to speak to the crowd. Newspapers would run side-by-side comparisons of the two. One of the issues: Metzenbaum’s financial records, which would reveal nothing illegal but came out slowly enough to make people wonder. Glenn pulled ahead in the polls and then Metzenbaum made a mistake that would seal the primary. He said that John Glenn had never held a job.

As the end of 1973 approached, the Watergate scandal was developing, Nixon’s attorney general resigned in protest, and Nixon appointed the Senator from Ohio, William Saxbe, to the post. That meant a special election in 1974 and John Glenn went head-to-head with Howard Metzenbaum in the Democratic primary. Their styles were somewhat different. While Metzenbaum hosted $100-a-plate fundraisers, Glenn put on 99-cent corned beef dinners and stood on tabletops to speak to the crowd. Newspapers would run side-by-side comparisons of the two. One of the issues: Metzenbaum’s financial records, which would reveal nothing illegal but came out slowly enough to make people wonder. Glenn pulled ahead in the polls and then Metzenbaum made a mistake that would seal the primary. He said that John Glenn had never held a job.

It was so obviously a desperation move that Glenn tried to ignore it at first. Metzenbaum had never been in the military and kept repeating his remarks at every stop. Newspapers picked up on the comments and Glenn finally decided to give his answer at their final debate. When it was time for closing remarks, he looked at his opponent. “Howard, I can’t believe you said I have never held a job.” With that, he launched into what became known as his “Gold-Star Mother” speech. He summarized his Marine career spanning more than twenty years and two wars and his experience as an astronaut, where “it wasn’t my checkbook, it was my life on the line.”

He addressed Metzenbaum directly: “I ask you to go with me, as I went the other day, to a veterans’ hospital, and look those men with their mangled bodies in the eye and tell them they didn’t hold a job. You go with me to any gold-star mother and you look her in the eye and tell her that her son did not hold a job.

“You go with me to the space program, and you go as I have gone to the widows of Ed White and Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee and you look those kids in the eye and tell them their dad didn’t hold a job.

“You go with me on Memorial Day coming up and you stand in Arlington National Cemetery – where I have more friends than I like to remember – and you watch those waving flags and you stand there and you think about this nation and you tell me that those people didn’t have a job.

“I tell you, Howard Metzenbaum, you should be on your knees every day of your life thanking God that there were some men, some men, who held a job. And they required a dedication of purpose and a love of country and a dedication to duty that was more important than life itself. And their self-sacrifice is what has made this country possible.

“I have held a job, Howard.”

The speech earned John Glenn a standing ovation from the live audience. He won the primary by 100,000 votes and went on to win the election. He was finally going to the Senate.

In The Senate

John Glenn was officially sworn in on January 14, 1975 and settled in quickly. He asked for appointments to the Government Operations and Foreign Relations committees. He got Government Operations immediately but had to wait for an open slot in Foreign Relations. He turned down several invitations for appearances so he could focus on being an effective senator and had a hand in amending several energy, civil rights and foreign policy bills.

He made friends with majority leader Mike Mansfield from Montana, who invited him along on a trip to China. Glenn agreed and they scheduled the trip for mid-September to mid-October 1976. The revolutionary leader Mao Tse-tung died just before the trip but Chinese officials urged them to come anyway. China was making efforts toward modernizing their infrastructure, including adding electricity to rural areas, and Glenn got a chance to meet an engineer who had graduated from the University of Illinois and was designing generators. The engineer was reluctant to talk to Glenn, which was fairly typical. China did not want to reveal that it was relying on Western education for much of its effort.

Glenn got his appointment to the Foreign Affairs committee and gained an interest in a third called the Special Committee on Aging. His father had died of cancer and, because of the medical expenses, could have lost the house Glenn had grown up in if it wasn’t for his help. Annie had also visited several nursing homes and told Glenn about them. The committee was purely for informational purposes but Glenn wanted to find out more about what could be done for elderly people.

His posting on the Foreign Affairs committee opened up opportunities to travel worldwide. He attended the ceremony in which the Solomon Islands became independent and met a man named Marija, who led a tribe that had been discovered only seventeen years before. Glenn and Marija exchanged gifts. Glenn brought a gold bicentennial medal on a red ribbon that he hung around Marija’s neck. Marija gave him a medallion of sinew, bone and feathers that represented a tribal belief that the spirits of dead people and animals went to the moon. Somebody had told Marija that Glenn had been to the moon, which was probably a mistranslation.

Glenn met King Hussein of Jordan, the shah of Iran, and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat as he traveled around the Middle East to help President Carter’s peace efforts. The luxury of some of these leaders’ homes astonished him. Glenn got along well with King Hussein, who was a pilot and often relaxed by flying fighter jets. During one of Hussein’s visits to the U.S., Glenn gave him a tour of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Carter and Glenn clashed on the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty, SALT II. Glenn wasn’t against the basic terms of the treaty, but world events prevented the U.S. from being able to verify Soviet activity. Glenn didn’t trust the Soviets to keep up their end without verification. Mrs. Carter was pretty icy about it during one speech and did not acknowledge the Senate’s role in approving treaties. The treaty was signed but never ratified.

In 1980, Carter lost the election primarily due to circumstances outside his control, but Glenn was elected for a second term. Glenn would disagree with the new President Ronald Reagan on several issues, including Reagan’s cuts in funding for education and scientific research. Glenn also wasn’t thrilled with the way the political system was degenerating into a series of labels like conservative and liberal. He felt that the centrist position was being neglected and he began to consider running for the presidency in 1984.

Presidential Campaign

John Glenn talked it over with his wife first, knowing how she felt about speaking to crowds. She was supportive and had given her first full-length speech to a crowd of three hundred women in Canton, Ohio, not long before, bolstering her confidence. With help from his political staff, he identified the main obstacles to victory. Teddy Kennedy was considering a presidential run and would have been a favorite, but he would ultimately decide against it. Glenn was also trying to live down a lackluster speech he had given at the 1976 Democratic National Convention. He worked with a media consultant to improve his speech delivery style and write a speech articulating his core beliefs and hope that America would not splinter into a bunch of bickering factions.

John Glenn talked it over with his wife first, knowing how she felt about speaking to crowds. She was supportive and had given her first full-length speech to a crowd of three hundred women in Canton, Ohio, not long before, bolstering her confidence. With help from his political staff, he identified the main obstacles to victory. Teddy Kennedy was considering a presidential run and would have been a favorite, but he would ultimately decide against it. Glenn was also trying to live down a lackluster speech he had given at the 1976 Democratic National Convention. He worked with a media consultant to improve his speech delivery style and write a speech articulating his core beliefs and hope that America would not splinter into a bunch of bickering factions.

With Kennedy out of the picture, the current favorite was Mondale with a 59% approval rating. Glenn stood at 28% but thought he could catch up. He gave a successful speech at Texarkana in 1982 and, as he continued his explorations into 1983, became convinced that he could beat Reagan in the general election if he could nail down the Democratic primary. On April 21, 1983, he declared his candidacy at the high school that had been renamed for him.

He gained ground in the polls, became overconfident, and made mistakes. He didn’t focus enough on the traditional early battlegrounds of primary elections like New Hampshire and traveled too much. It hit home when he stopped for a visit to the National Air and Space Museum. He was sharply reminded of the trust and comradeship of the people in the Mercury program and wondered if his decision to run had been a mistake. His daughter, Carolyn, tried to encourage him but Mondale began to gain ground again. The movie version of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff was considerably less than brilliant and did not help. He lost badly in the Iowa primary and it had a domino effect. He pulled out of the race with his campaign more than $3 million dollars in debt and had to ask his Mercury friends for help. They pitched in on the condition that he never run for president again.

Back To The Senate

John Glenn returned to the Senate and jumped right back into the legislative process. The Government Operations committee had been renamed Government Affairs but still had the same duties of overseeing the workings of government. A delegation of citizens from Fernald, Ohio came to his office with concerns about high cancer rates around the nuclear weapons plant there. Glenn promised to look into it and investigated with help from committee staff members. He found that the managers had let safety and emissions standards lapse and the investigation snowballed until it involved similar plants in Washington State, Colorado and South Carolina. The mess would take years and billions of dollars to clean up. Glenn capped his investigation by introducing legislation that created the Defense Nuclear Facility Safety Board.

He was elected to a third term in 1986 as part of a sweep that put the Democrats in control of Congress. He helped draft and pass legislation aimed at improving government efficiency, which did not earn much attention from the press but which he considered solid work. He was proud of his role but a challenge to his integrity would rock his career in 1989.

The savings and loan industry had been systematically deregulated, leading to some questionable practices. In 1987, a lawyer representing Charles Keating, the head of Lincoln Savings, contacted Glenn with allegations that an audit being run by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board had gone on so long that it amounted to harassment. Senator Dennis DeConcini from Arizona arranged a meeting that included Glenn and John McCain. When Glenn heard that there could be criminal charges, he decided not to get involved but made the mistake of accepting an invitation to have lunch with Keating and House Speaker Jim Wright. A year later, Lincoln Savings became one of the casualties of the savings and loan crisis. Glenn’s campaign had accepted contributions from Lincoln Savings and he became known as one of the Keating Five.

It made him mad and he resolved to fight it. The Ethics Committee investigated and Glenn gave them all his files from his period. If there was a scrap of paper on his desk he thought would help, he made sure they got it. Robert Bennett recommended that Glenn and John McCain be eliminated from the investigation, but this was rejected. The investigation dragged on for three years and Glenn was forced to accept a mild rebuke that he had “exercised poor judgement” in accepting the lunch invitation.

In 1992, he ran for a fourth term and also helped campaign for Bill Clinton. It was a hard-fought and highly negative campaign, during which his opponent made an issue out of the Keating affair, but he won along with a sweeping Democratic victory in Ohio. It would be his last term in the Senate.

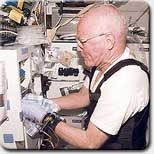

Thoughts Of Returning

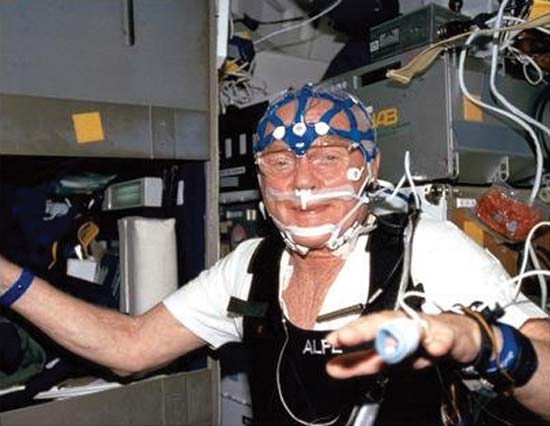

Glenn continued to fight for solid legislation and also championed NASA in the Senate. After the Apollo missions, public interest had steadily declined and support in the Senate was reduced along with it. In 1995, he was preparing for a debate over support for the International Space Station when he came across a book titled Space Physiology and Medicine. The topics included the effects of weightlessness, which included osteoporosis, disruptions of sleep patterns, and cardiovascular changes. Intrigued, the 73-year-old Glenn recalled his years on the Special Committee of Aging and realized that the symptoms of weightlessness were similar to the effects of aging. It was enough to give him an idea.

Return to Space

Obstacles

Glenn was interested in learning how an older person would react to being weightless. Would he avoid some of the effects of “space aging?” Would he recover as well as younger astronauts did? He discussed the issue with experts on aging and a few NASA doctors. Some of them hoped to research the subject at some point in the future and Glenn thought, “Why not now?”

He broached the subject with NASA director Dan Goldin, who thought Glenn was joking. Glenn was in regular contact with Goldin on Senate business and continued to bring it up. Finally, Goldin said, “You’re serious about this, aren’t you?”

“Serious as can be,” said Glenn.

Goldin finally gave his okay, on two conditions. The attempt had to produce good science, and Glenn would have to pass the same physical exam given to current astronauts before they were cleared for flight. Glenn agreed and made his request to the physicians at the Johnson Space Center when he went in for the annual physical that all retired astronauts received. Meanwhile, the questions he hoped to answer were referred to a committee for a peer review.

Goldin recalled that Glenn frequently called NASA employees for updates during the review process. Glenn claimed that he was not deliberately putting pressure on anyone and Goldin did agree that he was keeping his word not to get the White House involved. Goldin got a chance to talk to Glenn’s old friend, Tom Miller, about all the phone calls his staff was receiving. Miller just informed him, “You’re in contact with the most persistent person I’ve ever known.”

His family’s response was initially less than enthusiastic. They had hoped that Glenn, well into his 70s, was done taking risks. The usually supportive Annie’s initial response was, “Over my dead body.” Dave would tell Dan Goldin at a banquet he attended with his father, “I’m totally against it.” They eventually accepted the idea and Annie became as interested in the science as John Glenn was. By this point, the media had caught wind of rumors that John Glenn was considering a flight on the Space Shuttle and ran with it. On January 15, 1998, he got the hoped-for phone call from Goldin. They were going to announce that John Glenn was going back into space at a news conference the next day.

Crew Reactions

Imagine how you would feel if you got to work with one of the legends of your profession. The crew of STS-95 weigh in on their chance to fly on the Discovery with John Glenn, as told in this series of interviews.

Commander Curtis Brown

Commander Curtis Brown

This one is special because we have Senator Glenn on board, and so we’re thrilled to have that coverage, we’re thrilled to have him on board. How I feel about being the commander of Senator Glenn — I’ll be honest with you, I kind of put that aside, I don’t think much about it I know that’s probably a boring answer but I try to keep that separate and my job is organize the crew and plan for the mission, get the science done and when I get back I’ll kind of think about what’s really happened and put the emotional side into it. But we’re trying to focus and keep the crew focused and go do the mission, but it’s not always easy to keep everyone focused with the media.

Pilot Steve Lindsey

Pilot Steve Lindsey

Well, just to be assigned to this flight was a complete surprise to me. I had no inkling this was going to happen. So I was surprised to be assigned, and then when I found out I was going to fly with John Glenn… I feel really honored, that I’m getting the opportunity to do this. I know this is an opportunity of a lifetime for me; I never thought I would even meet any of the original seven astronauts let alone get a chance to fly with one. So I feel very privileged to be a part of this crew and a part of this flight — and I certainly feel privileged to get to know and work with Senator Glenn.

Mission Specialist Scott Parazynski

Mission Specialist Scott Parazynski

Well, my initial response was this is too good to be true, this is science fiction. I think to put it in perspective, this would be like a physicist having the opportunity to make a great discovery with Albert Einstein, or a mountaineer to summit a Himalayan mountain with Sir Edmund Hillary, or to play baseball with Babe Ruth, or soccer with Pele: this, for an astronaut, is about as exciting as it gets. And so I’m thrilled to be a part of this flight. I think on a more global scale, certainly John has been a hero and an inspiration to young people, for many, many years, but the exciting part now in history is that he’s going to become a role model and hero for senior citizens. I’ve heard it many, many times; people will say well, if John Glenn can go and fly in space at age 77, I ought to be able to, you know, tackle this project or that. I think that’s his continuing legacy.

Mission Specialist Pedro Duque

Mission Specialist Pedro Duque