Neil A. Armstrong

The most famous American astronaut, Neil Armstrong is best known for being the first to set foot on the moon. But did you know…

The most famous American astronaut, Neil Armstrong is best known for being the first to set foot on the moon. But did you know…

Neil Armstrong is one of the first civilian astronauts. Neil Armstrong had been a Navy pilot, but had retired before applying to NASA as an astronaut. He was part of the second group of astronauts, the Mercury Seven having been chosen from among pilots in the Navy, Air Force and Marines.

He also flew the abortive Gemini 8. A thruster had malfunctioned, forcing them to make an early reentry.

First Man On The Moon

Wapakoneta, OH

Wapakoneta, Ohio, is most famous for being Neil Armstrong’s hometown. However, between Armstrong’s birth on August 5, 1930, and 1944, his family moved sixteen times, finally settling in Wapakoneta. He was the oldest of three children and his parents, Viola and Stephen, remembered him as a quiet and shy boy who never seemed to get upset about much. He was apparently not much of a troublemaker though his siblings suspected that he got out of things simply by being the favorite.

He was a bookworm and did so well in school that they promoted him to the third grade early. He was especially good at science and, in high school, was encouraged by science department head John Grover Crites. Crites recognized that Armstrong had an analytical mind and believed that he would do well in any field involving research.

Armstrong was active in Boy Scouts starting while his family lived in Upper Sandusky. Protestant minister J.R. Koenig helped form and lead the local troop after the U.S. entered World War II. As part of Scouting activity, Armstrong made airplane models to help the military improve their aircraft recognition efforts. Koenig was eventually replaced by Ed Naus and Steve Armstrong and they helped the troop start a monthly newspaper called The Pup Tent News.

Several legends would grow up around Armstrong’s youth. One fellow named Jacob Zint was an amateur astronomer who had built an observatory on his property. He would talk about how Armstrong came out to look through the telescope at the moon and they would discuss subjects like the possibility of life on other planets. Zint claimed that the young Armstrong fantasized about visiting the man in the moon. Armstrong didn’t recall being out at Zint’s place more than once and that had been carefully arranged by the scoutmaster so he could earn a badge. He never insisted that Zint stop telling his stories and Zint’s telescope is now in the Auglaize County Museum in Wapakoneta.

Like many families during the Depression, the Armstrongs didn’t have a lot of money for luxuries. His father had a job and that made Neil Armstrong seem rich to a lot of his peers. Armstrong found his first job at the age of ten, mowing the lawn at the Old Mission Cemetery in Upper Sandusky. He also worked in a bakery, helping make doughnuts and bread and scraping the dough mixer clean. When they moved to Wapakoneta, he found work at a grocery store. He saved a lot of his money for college.

Armstrong never went on more than a few dates and didn’t have a steady girlfriend in high school. An outing with his senior prom date turned into an adventure. He borrowed his father’s new Oldsmobile and took Alma Lou Shaw-Kuffner out on a double-date with Dudley Schuler and Patty Cole. They were going to go on an all-nighter out to Dayton but Armstrong began having second thoughts. What if they got in a wreck? So, they decided to go to a local amusement park, which was closed when they got there. They just drove around and found a late-night diner at three in the morning. On the way back home, Armstrong fell asleep at the wheel and they went into a ditch. All four of them tried to push the car out and the girls got grass stains on their dresses that they were hard-pressed to explain afterwards. A passing car pulled over and the driver helped them get it out of the ditch.

Armstrong graduated from high school at the age of sixteen and decided to take up flying. When recalling the Zint story, he would say that his dreams all had to do with airplanes, not space flight. He had taken his first airplane ride at the age of six years old and, during his senior year in high school, found three veteran army pilots who were willing to teach him how to fly. Receiving his private pilot’s license meant more to him than getting his driver’s license. When he heard that Chuck Yeager had broken the sound barrier in an X-1, he regretted not having been born a generation earlier. He felt that he had missed out on the real heroic age of aeronautics.

Purdue University

For all that, one era ends and another begins. As Neil Armstrong went into his freshman year at Purdue University, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, NACA, was preparing new facilities to study transonics, supersonics and hypersonics. The transplanted German rocketry team at Redstone Arsenal also launched reconstructed V-2 rockets to an altitude of 70 miles, and then 83 miles, with the cargo of one monkey. Partial pressure suits were also seeing use at high altitudes for the first time. It became obvious to everybody except politicians in Washington, D.C., that outer space was the new high ground and the term “aerospace” was coined.

For all that, one era ends and another begins. As Neil Armstrong went into his freshman year at Purdue University, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, NACA, was preparing new facilities to study transonics, supersonics and hypersonics. The transplanted German rocketry team at Redstone Arsenal also launched reconstructed V-2 rockets to an altitude of 70 miles, and then 83 miles, with the cargo of one monkey. Partial pressure suits were also seeing use at high altitudes for the first time. It became obvious to everybody except politicians in Washington, D.C., that outer space was the new high ground and the term “aerospace” was coined.

Armstrong chose to major in aeronautical engineering with his education paid for by the Navy through the Holloway Plan. At the time, the aeronautical engineering program at Purdue was very hands-on, though it would later gravitate toward theoretical. During his freshman year, Armstrong earned a 4.65 GPA out of a 6.00-point scale, the equivalent of a low B. Changes to the Holloway Plan led to an interruption in his college career at an inconvenient time. He was taking Thermodynamics I in fall of 1948 and wanted to follow it up right away with Thermodynamics II in the spring, but the Navy called him in early. He reported for Navy flight training in February 1949.

Flight Training

Neil Armstrong reported to Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida, where he became one of forty midshipmen in Class 5-49. Pre-Flight training included four months of classes that included Aerial Navigation, Communications, Engineering, Aerology, and Principles of Flight. Many of the classes were taught by Marines. One particularly tough Marine named Lieutenant Mano was in charge of Physical Training. Neil Armstrong was a strong swimmer but otherwise not much for physical activity. He believed that Mano gave everybody low grades. The slightest lapse of discipline was penalized with demerits and disciplinary walking tours and everybody in the class walked at least one tour during Pre-Flight.

Armstrong finished Pre-Flight with the equivalent of a high “B” on the grading scale. Stage A of flight training took place at the largest of Pensacola’s auxiliary fields, Whiting Field. This stage consisted of eighteen dual instruction flights, a check flight, and then the student would fly solo in a North American SNJ. The instructor noted that Armstrong had difficulty with coordination and simulated emergencies but passed him on to Stage B anyway.

Stage B, manuevers, went reasonably well though Armstrong didn’t stand out. One instructor noted that he would probably make an average pilot. He rated mostly “average” or “above average” during Stage C, aerobatics. During Stage D, Armstrong had some trouble with altitude control but gradually improved. His two night flights, Stage E, went fine and he finished those five stages by Thanksgiving 1949.

Stage F, formation flying, went so poorly that Armstrong was assigned one increment of extra instruction. Stage G, gunnery, went well. In February 1950, he went out to Corry Field for Field Carrier Landing Practice. A runway had been painted to look like an aircraft carrier and he spent the next three weeks learning to follow the signals of a Landing Signal Officer (LSO). Armstrong’s trouble with altitude control came back but he improved with practice. Finally, he was ready for the equivalent of a final exam, six landing attempts on the light carrier USS Cabot. He succeeded and graduated from Basic Training to Advanced.

When asked to choose what kind of plane he wanted to fly, he requested single-engine fighters. He got his wish and took advanced training in an F8F-1 Bearcat. He received only one unsatisfactory mark during advanced training and, by July 1950, was ready to try carrier landings in the Bearcat. One classmate, Herbert Graham, remembered there was a competition between him and Armstrong to see who could get his six landings in first. Armstrong and Graham were tied, five to five, and Graham was forced to take a wave-off because the deck hadn’t been cleared. When Armstrong made his attempt, he became the first in his class to make all six landings. He graduated from training, now a fully fledged naval aviator.

Fighter Squadron 51

Armstrong asked for, and got, an assignment on the West Coast, with the Fleet Aircraft Service Squadron 7 at Naval Air Station San Diego. Officially, he was placed on pool status while he waited for assignment to an air group. In November 1950, he was assigned to Fighter Squadron 51 (VF-51), with Lieutenant Commander Ernest M. Beauchamp in command of the squadron. Beauchamp hand-picked most of the aviators in his squadron, even going toe-to-toe with the commander of Air Group 5 (CAG) to get four experienced lieutenant junior grade pilots for his core group.

Beauchamp never thought of Neil Armstrong as being a “mere” midshipman and Armstrong was promoted to ensign quickly enough. To the squadron commander, he was one of several gifted junior aviators in VF-51. When he wasn’t on duty, Armstrong’s hobbies included reading and carving models of planes and boats, one of which he gave to a friend so he could give it to his children. His interest in education set him apart and he could often be found demonstrating an aerodynamic principle or algebra problem to interested crewmen.

He logged more than 150 hours in VF-51′s F9F Panthers and impressed Beauchamp enough to be assigned as assistant education officer and assistant air intelligence officer before their ship, the Essex, received orders sending them to Hawaii. While in Hawaii, the planes were fitted with bomb racks and VF-51 became a ground attack squadron, a huge letdown for the aviators who hoped to face off against MiGs being flown by North Korea. The Essex went on to NAS Yokosuka in Japan after truce talks in Korea fell through.

Beebe, the Commander of the Air Group, often requested Armstrong as his wingman. This could be a risky honor because Beebe frequently risked his neck to take a second look at targets they had just bombed. Beauchamp once criticized him for keeping the air group out so long that they barely had enough fuel to get back to the Essex.

On his seventh Korean combat mission, Armstrong came close to losing his life. There are conflicting stories about what actually happened on September 3, 1951 but most of the important details agree. Armstrong’s targets included a bridge in a zone known as “Green Six,” not very far from the interior border of South Korea, when Frank Sistrunk from VF-54 was hit by anti-aircraft fire and crashed. At almost exactly the same time, Armstrong’s plane took damage and came so close to hitting the ground that he later commented, “Twenty feet from Mother Earth at that speed is awful doggone low!” Initially, it was believed that he had been hit by flak but later evidence suggested that he had run into a common booby-trap: a strung-up cable meant to take down low-flying aircraft. He certainly lost part of one of his wings though there was some disagreement on whether he lost two feet, three feet or six feet of it. He made it back to friendly territory and ejected near station K-3. He landed in a rice paddy with no injuries more serious than a cracked tailbone and a damaged helmet. Armstrong returned to the Essex the next day on a mail delivery boat. Some of the other members of the air group teased him a bit about owing the Navy a new helmet. Nobody ever knew what happened to his lost Panther.

Not even two weeks later, the Essex would see the worst disaster of the entire cruise. An F2H Banshee from VF-172, flown by John K. Keller, took damage in a mid-air collision, causing loss in aileron control and flaps. Beauchamp was in a landing pattern and may have seen the whole thing from the air. He certainly heard Keller call for a straight-in with something close to panic in his voice. He cleared the landing approach. Keller neglected to lower his tailhook, vital for catching one of the arresting wires and coming to a complete stop in the limited space of an aircraft carrier deck. Peering into the setting sun behind the plane, the tailhook spotter and LSO thought the tailhook was down. The Banshee bounced into the deck at 130 knots, went right over the heavy crash barriers, and slammed into a row of aircraft. Some of them had just landed and the pilots hadn’t yet left their airplanes. Others were fully fueled and the whole thing exploded. Seven men died and sixteen were seriously injured, most from burns. They were forced to push some of the planes overboard, including the Banshee with the dead pilot still inside. Beauchamp and his division landed on the nearby Boxer and stayed overnight while the Essex‘s crew sorted out the mess. Neil Armstrong was luckily on duty in the ready room and never saw the accident.

This and other losses were hard on air group morale. The worst of it was that they were only going after minor targets: bridges, trucks, trains, even a few oxcarts. It got so bad that some of the senior officers began to suspect sabotage. Five days after the Banshee accident, Essex returned to Japan for ten days of badly needed R&R.

Back to Korea

Armstrong flew several air patrols and photo escort missions during the Essex‘s second tour in Korea. The air group lost only three pilots during that tour, mostly due to a slowdown in the fighting, and it got so boring that one pilot vented by jumping on an airplane wing and exclaiming, “Let’s go shoot something. Anything!”

Armstrong flew several air patrols and photo escort missions during the Essex‘s second tour in Korea. The air group lost only three pilots during that tour, mostly due to a slowdown in the fighting, and it got so boring that one pilot vented by jumping on an airplane wing and exclaiming, “Let’s go shoot something. Anything!”

The Essex returned to Yokosuka for refurbishing on October 31 and went back to Korea on November 12. With winter approaching, the weather became miserable and flying was impossible some days. When they did fly, they would often unload extra ordnance after a mission by dropping them on targets of opportunity. During their third tour, the air group had no casualties and, during their next layover in Japan, the Essex put on a Christmas party for Japanese orphans.

The Essex‘s fourth tour was the longest and nastier than the first one had been. Armstrong totalled more than 35 hours in the air. Morale plummeted, especially after the admiral announced that their replacement would be late relieving them. Two deaths hit them especially hard. One was Rick Rickleton, who was looking forward to returning to the U.S. after the war but was shot down and died in a fireball when his plane hit the ground. The other was Leonard Cheshire. Armstrong remembered long discussions with him on a variety of subjects that included philosophy, theology, literature and history when they were both off-duty. He was hit by anti-aircraft fire and went down with his plane in flames.

The fifth tour lasted only two weeks starting February 18, 1952, and Armstrong flew 13 missions. They headed back to the U.S. mainland with brief stops in Japan and Hawaii on the way. Like most in his air group, Armstrong brought home several medals, including the Air Medal, Gold Star and Korean Service Medal and Engagement Star.

Research Pilot

Once Armstrong returned to the States, he finished up his degree at Purdue and then considered his options. He stayed in the U.S. Naval Reserves until 1960, at first flying with the Naval Reserve Aviation Squadron 724 based just outside Chicago.

The idea of being a test pilot appealed to him. If he took a position with a private aircraft company like Douglas Aircraft, he could become a production test pilot, testing each plane of a particular model as it rolled off the assembly line. He could test new airplane models as an experimental test pilot. Armstrong was especially interested in becoming a research test pilot, with duties similar to experimental test pilots. He would help develop the science and technology of flight.

The National Advisory Committee of Aeronautics (NACA) was heavily involved in flight research and is most famous for being NASA’s predecessor along with its work with transonic and supersonic research. Most of NACA’s resources would be rolled up into the new agency. It was dabbling in some now-familiar space technology, including a centrifuge for testing the effects of multiple Gs, and some rocket-powered planes like the D-558-2 Skyrocket, X-1 and X-15 planes. Several legendary names in NASA worked for NACA in various capacities, including Walt Williams and Bob Gilruth. Armstrong put in his application at NACA’s High-Speed Flight Station, located at Edwards Air Force Base.

Edwards had no openings but passed the application around to other NACA facilities. The Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio needed a test pilot and Armstrong was offered the job. It was the lowest-paying position Armstrong was offered but he took it anyway. It felt like a good fit for him and it meant he could stay in Ohio. He had met his first wife, Janet Shearon, at Purdue University and wanted to stay close to her.

Armstrong’s projects included new anti-icing systems for aircraft, and also investigating heat transfer at high Mach numbers. Mach numbers are multiples of the speed of sound and one T40 rocket launched by a test pilot reached Mach 5.18, or 5.18 times the speed of sound. Armstrong worked at Lewis for five months and then a position opened up at Edwards Air Force Base. Edwards was where Chuck Yeager had first broken the sound barrier in an X-1 plane and many of the revolutionary new planes like the X series were being tested. When asked if he would like to transfer out there, he jumped on it. He made one stop in Wisconsin on the way out west so he could marry Janet Shearon.

Neil and Janet Armstrong moved into an isolated cabin with no electricity and minimal plumbing. Installing modern conveniences was an ongoing project. For all that, they enjoyed the privacy. Their son, Eric, and first daughter, Karen, were born while they were living in that cabin. Armstrong carpooled to work with a few other NACA employees and, since being a test pilot wasn’t strictly an 8-to-5 job, was sometimes late picking up the others. He took some ribbing for it and one of the employees remembered that he gave as good as he got.

Armstrong was initially one of the youngest pilots there and started out flying chase in a P-51 Mustang or R4D. His job was to fly close to the plane being tested and observe its flight. It was fairly typical for one of the X planes to be attached to a B-29 bomber’s underbelly and flown up to a height of 30,000 feet or more. Then, it would be dropped and fly on its own. With a plane model this new, things could go wrong in a hurry. The rocket engine on the X-1A had a faulty gasket that exploded when the test pilot pressurized the liquid oxygen and alcohol that served as fuel. One test pilot barely had time to scramble out of the plane into the bomb bay of the B-29 before they had to jettison the X-1A.

Two projects on the drawing board were the X-15 and the Dyna-Soar, both meant to test the possibility of taking manned winged vehicles up to hypersonic speeds above the atmosphere. This was about the same time the more famous Mercury Project was using rockets to send astronauts up in capsules whose shapes reminded Gus Grissom of the Liberty Bell. Neil Armstrong took one fighter jet up to 90,000 feet, a point at which atmospheric drag was minimal and Newtonian physics began to take over. He had to shut off his engine at above 70,000 feet and manuever using jets of hydrogen peroxide. As he dived, he passed Mach 1.8 and the atmosphere became thick enough that he could restart his engine. Then, he made a routine landing.

The altitude record wouldn’t last. Chuck Yeager lost control of an NF-104A while flying up to 108,000 feet and was injured in the crash, and test pilots in X-15s successfully flew up to 200,000 and then 264,000 feet in pressure suits resembling those the Mercury astronauts wore.

In April 1962, Armstrong himself flew an X-15 up to 207,500 feet, or about 40 miles high. Until his first mission as an astronaut, it was a personal altitude record. He was testing a G limiter he had helped design and, while dropping back down into the atmosphere, lifted the nose of the plane just enough to let it balloon up to 140,000 feet. He ran into trouble and tried to turn, but there was not enough atmosphere. He finally managed to drop back down near Pasadena, forty-five miles from Edwards. He barely made it back to the base and landed in one of the dry lake beds. His fellow pilots kidded that he barely missed the diminutive Joshua trees that dotted the area.

There was a big debate about the best landing technique for the X-15. Another test pilot named Scott Crossfield preferred landings similar to the technique used to land on aircraft carrier decks but nearly bought it in two out of three tries. One method called for a high-speed, straight-in approach. Armstrong disliked both and developed a method that called for a spiralling descent from 40,000 feet. Armstrong’s technique was adopted by North American Aviation for their F-104, and Armstrong co-authored two papers about it.

Armstrong averaged ten flights a month until he joined the astronaut corps in September 1962. He consulted for the X-20 “Dyna-Soar” program run jointly by NASA and the Air Force and, for a while, it was a competition to see whether the Mercury Program or the Dyna-Soar would make it into space first. He might have stayed on as a test pilot, but a tragedy would lead him to consider a change of pace.

Muffie

During his teen-age years, Armstrong had a friend named Fred Fisher, who had a little sister named Karen “Cookie” Fisher. Cookie adored Armstrong, mostly because he paid attention to her, unlike most of her brother’s friends. Armstrong remembered Cookie and decided to name his daughter Karen, whom they affectionately called Muffie.

While on a trip to Seattle on Dyna-Soar business, Armstrong took his wife Janet, four-year-old Rick, and two-year-old Karen along. Karen and Rick enjoyed the public park near Lake Washington and, while leaving the park on June 4, 1961, Karen fell down. It seemed like a minor thing. She had a little knot on her head and a nosebleed and Janet thought she just had a minor concussion. A Seattle pediatrician recommended a thorough check-over and their regular doctor in California just recommended keeping an eye on her and bringing her back in a week.

Janet gave swimming lessons at a local pool and the mother of one of the students noticed that Karen was getting worse. She took Karen to the hospital for tests and called Armstrong. They diagnosed a rare brain-stem tumor and tried X-ray treatment. She lost, then gradually regained, her balance and, for the next month and a half, she seemed to be doing better. Afterwards, she had a relapse and they tried cobalt treatment, but it didn’t help. She went downhill fast and made it through Christmas 1961, finally succumbing to pneumonia on January 28, 1962.

It was rough on both Janet and Neil Armstrong. Neil Armstrong tried to internalize it and bury his grief in his work. He did not talk about Karen much, even to his closest friends. Janet, especially, was hurt by Neil Armstrong’s silence and it probably contributed to their divorce a few decades later.

After Karen’s death, Armstrong was involved in a series of mishaps that made some people wonder whether his personal life was affecting his flying. He didn’t think so, and he was certainly not the only test pilot to have difficulties with revolutionary planes like the X-15. One explosion in June 1960 left pieces of the rocket engine scattered across the landscape; the pilot was lucky to survive.

Before too long, the remaining family’s entire lives would change. NASA was looking for a second group of astronauts to follow the Mercury Seven, so Neil Armstrong decided to apply. He never speculated about whether the loss of his daughter was a factor in this decision though sources closest to him suspected that he needed something positive to focus on.

Astronaut Candidate

There were a few people in Houston who remembered Armstrong from the NACA days, including Walt Williams and Dick Day. They encouraged him to apply for the second group of astronauts. His application arrived a week after the official deadline, possibly because he was on vacation in Seattle while it waited on his desk at Edwards. Without a word to the rest of the selection committee, Dick Day slipped it in with the rest of the applications. He didn’t discuss it with very many people at Edwards and many of his friends were surprised when his name was among those who had been selected.

Chris Kraft, a flight director at NASA who had also worked for NACA, hardly knew Armstrong but didn’t think anything of the string of bad luck Armstrong had recently had while flying. When he found out that Armstrong’s daughter had died, he just decided that it might have affected his performance for the short term but it would have worked itself out and perhaps the flight surgeon and chief test pilot were partly at fault for not giving Armstrong a break from flying for a while.

The physical and psychological tests that every astronaut candidate had to go through were demanding but had been refined from what the Mercury Seven had endured. Holdovers included the blackout chamber that the candidates had to sit in for two hours. Armstrong tried to time it using the song “Fifteen Men in a Boardinghouse Bed.” The Mercury astronauts might also have recognized torture devices like the syringe they used to spray ice-cold water in their ears and a heat chamber that could get as high as 145 degrees Farenheit. Of the Mercury astronauts, Armstrong already knew Wally Schirra and Gus Grissom from Edwards and got to chat with a couple of them about the program.

During the four months between his application and the announcement, he kept busy with his work at Edwards. He flew test flights in the F-104, flew chase for some X-15 flights, received an award at an IAS event in Los Angeles, and presented a paper on an in-flight simulator that would evolve into the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV) at an AGARD meeting in France.

He got the call from Chief Astronaut Deke Slayton that he had been selected. There was some speculation that NASA had wanted a civilian test pilot for the public relations but NASA officials denied it. His association with NACA, and then NASA, as a test pilot probably counted for more than the fact that he was a civilian. He was asked to discuss it with no one but his immediate family until the public announcement.

I’ve Got A Secret

Not long after Armstrong was selected, his parents appeared on a 1960s game show, I’ve Got A Secret. If contestants could stump a panel of celebrities, they could win a prize of $80. The panel’s first guess was that the Armstrongs’ son was Jack Armstrong, “The All-American Boy,” from an adventure series that had been popular in the 1930s and 1940s. Then, they correctly guessed that the second group of astronauts, including Neil Armstrong, had just been announced earlier that day. Armstrong didn’t get to see the program.

The New Nine

On September 15, 1962, nine people checked into Houston’s Rice Hotel with the alias of Max Peck. Neil Armstrong was Max Peck Number Nine. The New Nine’s official first meeting took place the next morning, along with Walt Williams, Bob Gilruth, Shorty Powers and Deke Slayton. As the head of the Astronaut Office, Slayton would be their immediate boss. Armstrong and Elliot See were both civilians with Navy backgrounds. Charles “Pete” Conrad Jr., James Lovell Jr., and John W. Young came from the Navy. From the Air Force were Thomas Stafford, Frank Borman, James McDivitt, and Edward White. Several within NASA would come to regard this as the best group of astronauts they had ever assembled.

During this first meeting, Slayton gave them a warning about accepting freebies that made Gilruth blush. Public Affairs Officer Shorty Powers briefed them on the press conference, and then the nine new astronauts faced an 1800-seat auditorium full of reporters. NASA was better prepared for the expected media attention than they had been for the announcement of the Mercury Seven. This time, there was no John Glenn to give a spectacular speech to the press and the nine simply gave one- or two-sentence answers to most of the questions. Neil Armstrong certainly was less than impressed by the event: “[T]he questions at the press conference were typical, fairly unsophisticated questions, with answers to match.”

While Janet Armstrong prepared for the move to Houston, he spent the rest of September 1962 flying at Edwards. This included work on a paraglider known as the Parasev. If it had proven feasible, something like it might have been used for reentry during the Gemini program. Development on the paraglider became problematic due to technical issues and NASA was committed to water landings at the time anyway, so it was canceled.

With the rest of the New Nine, he watched Wally Schirra’s Sigma 7 launch on October 3. Then, he was officially reassigned to the Manned Spacecraft Center and carpooled with Elliot See for the 1,600-mile trip. To help his family move, he traded in both the cars he owned at the time for a spacious station wagon. The Armstrongs partnered with Ed White’s family to buy three adjacent lots and split the center one down the middle. Many astronauts lived in the same neighborhood and their families became a close-knit community.

An Astronaut’s Life

The Nine jumped right into work, starting with tours of contractors like Lockheed Aircraft Corporation and the Martin Company and a visit to Huntsville, Alabama, where they met the rocket team headed by Doctor Wernher von Braun. The company bosses often treated them to huge spreads of food and drink. It was something of a novelty to be treated like a celebrity.

Basic astronaut training included classroom courses on a variety of subjects like astronomy, orbital mechanics and spacecraft design. They had a modified KC-135 that came to be known as the “Vomit Comet” for zero-g training. Armstrong teamed up with John Glenn for survival training, an exercise that wasn’t always popular with the astronauts. When they went down to Panama for jungle training, Armstrong teamed up with John Glenn and carved “Choco Hilton” on the shelter they made, referencing some friendly members of the Choco Tribe that they had met.

Armstrong was introduced to helicopters for the first time in November 1963. Theoretically, flying a helicopter would better prepare astronauts for landing a Lunar Module on the Moon. It was less risky than the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle turned out to be but Armstrong thought it wasn’t as effective as a training tool, either. Not even an LLTV crash in which Armstrong was forced to eject changed his mind.

When handing out specializations, Deke Slayton did not miss the fact that Armstrong already had some experience with simulators at Edwards. Flight simulators were still in their infancy but already seen as a vital training tool at NASA. They weren’t perfect. NASA’s simulators had a bad habit of crashing in the middle of a run, and they didn’t do a very good job of simulating conditions on the day side of an orbit. Armstrong’s job was to help make sure the simulators accurately represented conditions they might encounter in actual space flight. With his pilot’s perspective, he helped the technicians make the simulators look more realistic to the pilot-astronauts.

Armstrong was the first of the New Nine to take on administrative duties at the Astronaut Office. Slayton put him in charge of operations and training. They were starting to put together the crews for the Gemini missions and Slayton asked him to help determine how many crews would be needed at any given time. Armstrong got a list of the planned launch dates for the Gemini and Apollo missions and worked backwards from each date to determine how long each crew would have to spend preparing and training for each flight. When preparations for Apollo began to overlap with Gemini, the number of needed crews grew to the point where NASA officials decided to select a third group of fourteen astronauts that included Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins.

House Fire

Even before the Apollo 1 fire issued a painful reminder of the risks of space flight, tragedies and near-tragedies began to strike the astronaut corps. Elliott See, Charlie Bassett and Theodore C Freeman were lost in accidents involving NASA’s fleet of T-38 planes. In the spring of 1964, the Armstrong family nearly lost their lives in a house fire.

Janet Armstrong woke in the middle of the night, smelled smoke, and woke Neil Armstrong. He investigated and yelled to Janet that the house was on fire. She tried to call the fire department with no luck, and then tried two emergency numbers. She ended up calling their neighbors, the Whites. Ed White had nearly qualified for the Olympics in the high hurdles before becoming an astronaut and leaped over the six-foot fence to help.

In the meantime, Neil Armstrong went to save their children. They had a ten-month-old son, Mark, whom he passed through a window to Ed White. Then, he went for six-year-old Rick. He had to hold a wet cloth over his face. He described those twenty-five feet he had to cross to Rick’s bedroom as “the longest journey I ever made in my life.” Rick was still alive and suffered no injury worse than a burn on his thumb. Armstrong put the cloth over Rick’s face and made it out to the backyard.

With White’s help, he pushed the cars out of the garage. The body of the Corvette he had gotten at a discount from a friendly Chevy dealer took some heat damage. They tried to fight the fire with hoses until the fire department arrived. The house burned to cinders and they lost many valuable mementos, mostly pictures and new furniture. They found Armstrong’s boyhood collection of model airplanes, most of them melted and twisted from the heat. But they were just glad they had made it out alive. They stayed at the Whites’ house for a few days, and then found an apartment where they lived until they could rebuild their house. Friends stepped up to the plate to help replace needed items they had lost in the fire.

Life went on, and so did Armstrong’s career as an astronaut. Neil Armstrong’s first crew assignment was as the backup commander of Gemini Five, with Elliot See as the backup pilot. If the prime crew of Gordon Cooper and Charles Conrad couldn’t fly, they would have stepped up to the plate. It proved unnecessary and Gemini Five made it only an hour short of the eight-day goal with a faulty fuel cell. Then, Neil Armstrong drew the assignment as the commander of Gemini Eight with Dave Scott as pilot.

Gemini 8

March 16, 1966

The primary goal of Gemini XIII was to rendezvous and dock with an automated spacecraft called Agena. This would be the first actual docking. Previous problems with the Agena craft had led to a change of goals for Gemini VI and they had successfully rendezvoused with Gemini VII. The plan also included an EVA by Dave Scott and a test of a digital computer to assist with guidance and navigation. Digital computers were still brand-new and the Gemini program was one of the first practical applications. The challenge appealed to Armstrong as a pilot.

The primary goal of Gemini XIII was to rendezvous and dock with an automated spacecraft called Agena. This would be the first actual docking. Previous problems with the Agena craft had led to a change of goals for Gemini VI and they had successfully rendezvoused with Gemini VII. The plan also included an EVA by Dave Scott and a test of a digital computer to assist with guidance and navigation. Digital computers were still brand-new and the Gemini program was one of the first practical applications. The challenge appealed to Armstrong as a pilot.

The Agena lifted off without problems at ten o’clock am, prompting a cool “Very good” from Neil Armstrong as he waited for liftoff in the Gemini. Gemini VIII lifted off at 11:40 am. Armstrong had seen the curvature of the Earth from forty miles up while still working on the X-15, but this was a first for Dave Scott. He asked his commander, “Hey, how about that view?”

“That’s fantastic!” Armstrong agreed.

Their duties did not leave much time for sight-seeing. When they did get a chance to look out the window, they spotted Hawaii and Armstrong picked out his old base at San Diego. Armstrong aligned the Gemini’s inertial platform, three gyroscopes that would keep track of yaw, roll and pitch angles and provide the spacecraft with some sense of direction. With a quick firing of the thrusters, he maneuvered the Gemini into the same orbital plane as the Agena’s. If the plane was off by even a little, they would have missed their target. They aligned their platform again for another burn, this time a simple repositioning in their plane. They found time for a meal of reconstituted chicken casserole and fruit juice before the next plane-change adjustment.

They began to catch up with the Agena, double-checking the computer’s results with an on-board chart and with computations on the ground. As they had found out when Gemini 5 splashed down 100 miles off target, seemingly small errors in their computations could have large results. The Gemini spacecraft gained a radar lock at 2:20 pm Houston time and, slightly over three and a half hours later, Armstrong and Scott were flying alongside the Agena. They flew around the automated spacecraft, taking pictures as they went. Though Dave Scott was technically the pilot, Armstrong did most of the actual flying at this point. He would have given Scott a chance to practice later if they had gotten the time.

They began to catch up with the Agena, double-checking the computer’s results with an on-board chart and with computations on the ground. As they had found out when Gemini 5 splashed down 100 miles off target, seemingly small errors in their computations could have large results. The Gemini spacecraft gained a radar lock at 2:20 pm Houston time and, slightly over three and a half hours later, Armstrong and Scott were flying alongside the Agena. They flew around the automated spacecraft, taking pictures as they went. Though Dave Scott was technically the pilot, Armstrong did most of the actual flying at this point. He would have given Scott a chance to practice later if they had gotten the time.

At 6:30, they were ready to dock. Armstrong inched the Gemini toward the Agena and, after a slight pause while Mission Control checked systems, he made the final connection. “Flight, we are docked! Yes, it really was a smoothie.”

The CapCom radioed up: “Roger. Hey, congratulations! This is real good.”

Scott chimed in, “You couldn’t have the thrill down there that we have up here.”

Capcom snorted. “Ha, ha, ha!”

They had no serious problems at first. Houston noticed some difficulties with sending commands up to the Agena and the velocity meter appeared to have gone offline. They weren’t very worried about it and had CapCom tell the Gemini 8 crew to send a Command 400 if the Agena started acting like a bucking bronco. A few minutes later, the tracking network lost Gemini 8′s signal. The bank angle began to go and Armstrong tried correcting it with the Orbit Attitude and Maneuvering System (OAMS). Because of the Agena’s history of faults, they thought it was a problem with the other spacecraft. They undocked and quickly realized that the problem was with the Gemini. A thruster was stuck open, causing them to go into a spin. They were making one complete revolution every second.

When they regained contact with the tracking network, Scott radioed back, “We’ve got serious problems here. We’re tumbling end over end. … We’re disengaged from the Agena.” Armstrong could only think of one solution, activate the reentry control system (RCS). They managed to regain control of the Gemini. The Agena was nowhere in sight.

When they regained contact with the tracking network, Scott radioed back, “We’ve got serious problems here. We’re tumbling end over end. … We’re disengaged from the Agena.” Armstrong could only think of one solution, activate the reentry control system (RCS). They managed to regain control of the Gemini. The Agena was nowhere in sight.

According to mission rules, once the RCS was activated, they would have to come back to Earth as soon as possible. Flight Director John Hodge calculated that they should splash down in an area about 500 miles east of Okinawa. Armstrong and Scott were not thrilled at having to come home early and even less happy that they would have to come down, as Armstrong put it, “way out in the wilderness.” It meant they would have to wait a while for pickup, in a spacecraft that already had a reputation for not making a very good boat. More than two hours later, frogmen from the recovery ship Leonard Mason opened the hatch. Armstrong was on board the destroyer first and Dave Scott, an Air Force officer, had to get an assist to make it up the Jacob’s ladder. Armstrong was especially unhappy that they hadn’t been able to complete their objectives and Scott missed his chance at EVA experience.

Wally Schirra joined them and, for once, the class clown of the Mercury astronauts wasn’t responsible for the comedy that played out when they returned to Okinawa. A large crowd had gathered for their arrival, along with a band and all kinds of banners. The Leonard Mason tried to pull in, with all the observers waving their banners and the band playing away. But a big wave pushed the destroyer right back out to sea. The banners came down and the band paused. They made a second approach, and the band started playing. Then, the sea pushed them right back out again. The embarrassed captain made the necessary adjustments and they were finally able to dock. By then, the band was starting to tire and some of the crowd had dispersed. Schirra was chuckling, and Armstrong might have enjoyed the joke better if he hadn’t been so upset about the early termination of their mission.

Post-Flight

A Mission Evaluation Team ruled that pilot error was not a factor in the emergency on Gemini VIII. A few other astronauts were disgruntled and some implied that they could have done better if they were up there. Much later, one even accused him of parlaying Gemini VIII into the first lunar landing. That was unlikely. Deke Slayton was in charge of crew assignments and would have considered Gemini VIII to be a minor issue at best by the time he chose the first man who would walk on the moon. In any case, it didn’t seem to affect his career as an astronaut much and Armstrong served on the backup crews of Gemini XI and Apollo 8 in due course.

Armstrong was annoyed at the press for hyping the thruster malfunction. He put in a call to Life magazine and the editor agreed to tone it down, though Armstrong was especially irked at them for not gaining the approval of NASA and the astronauts for their finalized article.

Armstrong and Scott both received NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal and Armstrong got a raise in pay, making him the highest paid astronaut at the time. By that time, the New York City ticker tape parades and dinners at the White House were a memory. Armstrong and his wife did attend a celebration at Wapakoneta. Armstrong wasn’t in much of a mood for celebrating but made the best of it. He received several gifts, including a lifetime membership to the Elks Lodge, and gave away little flags that he had taken on board Gemini VIII.

Goodwill Tour

By Autumn 1966, it had been a while since Neil Armstrong got a break from his astronaut’s duties. President Nixon’s idea of a goodwill tour in Latin America in October 1966 provided a welcome change of pace. The Armstrongs spent 24 days visiting 14 cities with Dick Gordon and George Low, who had recently become the head of the Apollo Applications office.

The people in all eleven countries they visited were certainly enthusiastic about the chance to see astronauts up close. At one point, George Low recorded, the crowds thronged around the motorcade, slowing progress to a snail’s pace. Armstrong and Gordon spent quite a bit of time signing autographs and shaking hands. The local security forces didn’t always seem to be prepared for the crowd’s response and they did have some minor incidents with local Vietnam protesters.

Armstrong artfully deflected any personal questions, preferring to discuss the technological and scientific aspects of the Gemini program. He had made an effort to learn Spanish and a little Guarani for the trip and Low was certainly impressed by his ability to talk to a crowd. The State Department and NASA officials were pleased by the positive results of the goodwill tour.

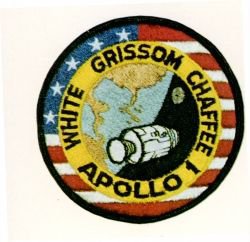

Apollo 1

On January 27, 1967, the space program mostly seemed to be on track. There was even hope that they would be able to put a man on the moon a couple of years early. One astronaut didn’t see it that way. Gus Grissom had repeatedly voiced concerns over problems with the Apollo spacecraft but nobody seemed willing to listen. Finally, in frustration, he took a lemon from a tree in his back yard and hung it on the spacecraft. A week later, he was dead along with fellow astronauts Roger Chaffee and Ed White in the Apollo 1 fire.

On January 27, 1967, the space program mostly seemed to be on track. There was even hope that they would be able to put a man on the moon a couple of years early. One astronaut didn’t see it that way. Gus Grissom had repeatedly voiced concerns over problems with the Apollo spacecraft but nobody seemed willing to listen. Finally, in frustration, he took a lemon from a tree in his back yard and hung it on the spacecraft. A week later, he was dead along with fellow astronauts Roger Chaffee and Ed White in the Apollo 1 fire.

Armstrong was attending the signing of a treaty governing the exploration and exploitation of space with a few fellow astronauts on that day. After the official ceremony, they mingled for a while, and then most of them returned to their respective hotel rooms. The person at the front desk gave him a message to call the Manned Spacecraft Center. The man on the other end of the line gave him the news about the fire and warned him to disappear until further notice so reporters couldn’t get hold of him.

The investigation of the fire took a matter of weeks and it would be months before they started flying in space again. Armstrong and many of his colleagues were devastated. They felt that a ground test that should have been low-risk was no place for three top-notch pilots to die. Armstrong had lost a friend and the neighbor who had helped him battle the flames when his house burned down. He and Janet attended the funerals. It was one of the few major space-related accidents he wasn’t asked to help investigate. Frank Borman represented the astronauts instead. Ten weeks later, the committee turned in its formal report and engineers began fixing the problems that had led to the fire.

A week after the formal report was turned in, Deke Slayton called a meeting with a select group of astronauts that included Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin. Slayton announced, “The guys who are going to fly the first lunar missions are the guys in this room.” According to the rudimentary plan taking shape, Apollo 11 would have been the full-dress rehearsal of the landing. Apollo 12 would have been the actual landing.

Lunar Landing Training Vehicle

Even before the Apollo 1 disaster, Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were studying the matter of lunar landing simulators. They could be making simulated lunar landings at Langley Field one day and be fitted for an LLRV ejection seat at contractor Weber Aircraft the next. They spent a lot of time in T-38s during this time.

Even before the Apollo 1 disaster, Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were studying the matter of lunar landing simulators. They could be making simulated lunar landings at Langley Field one day and be fitted for an LLRV ejection seat at contractor Weber Aircraft the next. They spent a lot of time in T-38s during this time.

The difficulty in developing devices that would fly like lunar landers primarily lay in the fact that they were trying to simulate lunar conditions on Earth. The Moon has no significant atmosphere and, in Earth’s atmosphere, they had to put up with winds and gusts. One option was a device called the Iron Cross, which didn’t actually fly but was meant for tests in near-vacuum conditions. Another idea was to carry the lunar simulator on a larger vehicle that would simulate conditions on the Moon. The result of that one looked to Armstrong like a Campbell’s Soup can with legs and an engine. Bell Aerosystems provided blueprints and two models of the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) they had developed.

The higher-ups in NASA didn’t like the risky LLRV and kept looking for a better alternative. A slightly improved version, called Lunar Landing Training Vehicles (LLTV), were funny-looking contraptions to pilot-astronauts used to ordinary jet planes. They were based on still-experimental vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) technology and looked like a plumber’s idea of what a lunar module might look like. Because of their appearance, they picked up nicknames like “the flying bedstead” and “the pipe rack.”

Helicopters were still in use as trainers and Armstrong was not the only astronaut to wonder about NASA’s reasoning. Bill Anders felt pretty much the same way: “That was, in a sense, almost bad training, flying helicopters.” The helicopter was good for judging trajectories and visual fields but the control system was different from what they had planned for the Lunar Module. Even after he had to eject from an LLRV that crashed, Armstrong continued to defend its use as a training tool. In fact, many of his colleagues were impressed by the cool attitude he had about the ejection. He simply returned to his desk to do some paperwork. Alan Bean asked about it and he only said, “I lost control and I had to bail out of the darn thing.” Bean could only think that if it had been anybody else, they would likely have been telling the story over drinks instead of just returning to their office!

Apollo

The Apollo 1 fire had threatened the Kennedy plan of putting a man on the moon by the end of the decade. It would take some bold action to get back on track and, after the successful Apollo 7 flight, NASA officials decided to send Apollo 8 into lunar orbit.

The Apollo 1 fire had threatened the Kennedy plan of putting a man on the moon by the end of the decade. It would take some bold action to get back on track and, after the successful Apollo 7 flight, NASA officials decided to send Apollo 8 into lunar orbit.

Neil Armstrong was the backup commander and woke early to have breakfast with the prime crew. At three in the morning, he didn’t have much of an appetite for the traditional filet mignon and scrambled eggs, so he stuck to coffee. While the prime crew suited up, he went out to Launchpad 39A to check the controls in the cockpit. This was going to be the first manned launch of the Saturn V. The unmanned test flights, Apollo 4 and Apollo 6, had been qualified successes. The main problem was the amount of pogo, a vibration caused by combustion instability. Engineers were sure they had pretty much solved the problem but Armstrong still thought it was a bold move to make the next Saturn V launch a manned one.

After launch, Armstrong watched the flight’s progress until well after the trans-lunar injection. Apollo 8 was well on its way to the moon. He returned to Houston and spent a lot of time at Mission Control. Deke Slayton found him there and conferred with him about his next assignment, Apollo 11. No one knew for sure whether Apollo 11 or 12 would be the first lunar landing. If anything went wrong in Apollo 8, 9 or 10, the actual landing could be pushed back to allow for more test flights.

During Armstrong’s conversation with Slayton, the subject of who his crewmates would be came up. It was possible that Buzz Aldrin could have been bumped in favor of Jim Lovell. Aldrin had occasionally gotten snipped at by other astronauts for making unsolicited suggestions, but perhaps Armstrong didn’t think it would be much of a problem. Replacing Aldrin would have meant it would be that much longer before Lovell got a chance to command an Apollo mission and Armstrong thought he deserved the chance. So, Armstrong decided not to pull him out of sequence and he ended up commanding Apollo 13. Armstrong never told either Lovell or Aldrin about his conversation with Slayton.

Apollo 8 made it back with no problems, and then Apollo 9 successfully tested the Lunar Module. Some inside and outside NASA wondered why they couldn’t make Apollo 10 the first actual landing, but those who favored a “dress rehearsal” held firm and 10′s Lunar Module got down to five miles above the lunar surface without a problem. Apollo 11 would be the first actual landing attempt.

The Apollo 11 Channel

Who’s On First?

At the press conference that introduced the Apollo 11 crew, the press asked the inevitable question: “Which of you gentlemen will be the first man to step out onto the lunar surface?” Armstrong didn’t quite seem to know how to handle that one and fielded it to Deke Slayton. Slayton answered: “I don’t think we’ve really decided that question yet. … I think which one steps out will be dependent upon some further simulations that this particular crew runs.”

It got to be quite a serious issue. Aldrin thought he had a good chance of being first and tried to talk to Armstrong about it. Armstrong was non-committal. When Aldrin went to some of the other astronauts for advice, many of them thought he was trying to lobby to be first and shut him down. Slayton got wind of Aldrin’s actions and told him that Armstrong would be out first, because he had seniority and he was the mission commander. It was a reversal of the roles they had established during Gemini. The commander had stayed in the cockpit while the pilot conducted EVA work.

They were certainly both aware that the first person to set foot on the moon would be the more famous. There was some speculation among outsiders that Armstrong had pulled rank. He denied it and insisted that the choice had entirely been in the hands of NASA officials. Several NASA insiders like Chris Kraft confirmed it. He had held a private meeting with Slayton, Bob Gilruth and George Low and they all agreed. Armstrong was exactly the kind of person they wanted to be first on the moon.

Training For Apollo 11

Armstrong wasn’t going to let the issue of who stood on the lunar surface first affect the work of training for the mission. Aldrin was probably lucky in this regard. Some later lunar mission commanders would have been less patient and preparing would have been stressful enough without the mission commander sparring with his Lunar Module pilot.

Armstrong wasn’t going to let the issue of who stood on the lunar surface first affect the work of training for the mission. Aldrin was probably lucky in this regard. Some later lunar mission commanders would have been less patient and preparing would have been stressful enough without the mission commander sparring with his Lunar Module pilot.

Being an astronaut is a more than full-time job even when they aren’t preparing for a mission and they were easily putting in more than sixty hours a week training and handling the details of preparing for the mission. Even so, Neil Armstrong did find time for family, as we see in the picture on the left of him preparing a couple of homemade pizzas. This picture was apparently taken a few months before the Apollo 11 mission.

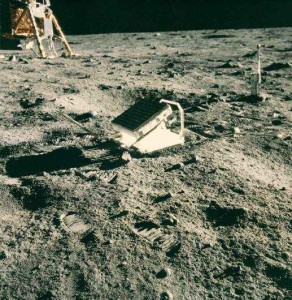

As the two who would walk on the moon, Armstrong and Aldrin often trained separately from the command module pilot, Michael Collins. While he worked on potential rendezvous scenarios in his own simulators, the two future moonwalkers practiced in the lunar module simulators and rehearsed setting up experiments and collecting samples in a mock-up of the lunar surface. Armstrong admitted later that they had been tempted to sneak a piece of limestone along to bring back as a sample.

Even though Armstrong wasn’t the confrontational type, the simulators did cause one documented argument among the crew when Armstrong blew a simulation and “crashed” the lunar module. Buzz Aldrin was not happy and told Michael Collins about it in the crew quarters later that night. Armstrong came out of his bedroom in his pajamas. According to Aldrin, he was annoyed about being woke up. Collins thought he was upset about being criticized over what should have been a learning experience and left the two of them to hash it out.

After the successful Apollo 10 mission, Deke Slayton had another chat with Armstrong: “How do you feel? Are you ready?” Armstrong told him, “Well, Deke, it would be nice to have another month of training, but I cannot in honesty say we have to have it. I think we can be ready for a July launch window.” That set the launch for July 16, 1969, with July 20 set as the date for the first landing.

CBS Coverage – Apollo 11 Launch

Launch Day

July 16, 1969

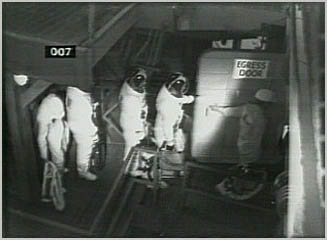

Launch days typically started early for the astronauts and, shortly after 6:00 am, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins were getting into their pressure suits with the help of technicians. The pressure suit was one technology that had improved steadily since Kennedy put America on course for the moon. Compared to the suits Armstrong had worn while flying in F-104s and X-15s, these ones seemed positively roomy.

Launch days typically started early for the astronauts and, shortly after 6:00 am, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins were getting into their pressure suits with the help of technicians. The pressure suit was one technology that had improved steadily since Kennedy put America on course for the moon. Compared to the suits Armstrong had worn while flying in F-104s and X-15s, these ones seemed positively roomy.

At 6:27 am, the crew headed out to the transfer van that would take them to Launchpad 39A, eight miles away. Their view of the Saturn rocket, the most powerful rocket ever built up to that point, was certainly impressive. The rocket, plus its payload of the command, service and lunar modules, stood 363 feet tall and would produce 7.5 million pounds of thrust when it lifted off. Armstrong was certainly aware of the dangers. To speed up the process, this rocket had been developed using the “all-up” method, combining tests of all three stages, instead of incrementally testing each stage separately as Armstrong would have preferred.

The White Room was the last room they would be in before they entered the command module Columbia. Fred Haise had already been there. He was part of the backup crew and had checked the cockpit to make sure every switch was in the proper position. Guenter Wendt gave Armstrong a little crescent moon he had carved out of Styrofoam and wrapped in aluminum foil. “It’s a key to the moon,” he said. In exchange, Armstrong gave him a ticket for a “space taxi” that read, “Good for a ride between any two planets.”

The White Room was the last room they would be in before they entered the command module Columbia. Fred Haise had already been there. He was part of the backup crew and had checked the cockpit to make sure every switch was in the proper position. Guenter Wendt gave Armstrong a little crescent moon he had carved out of Styrofoam and wrapped in aluminum foil. “It’s a key to the moon,” he said. In exchange, Armstrong gave him a ticket for a “space taxi” that read, “Good for a ride between any two planets.”

In the Columbia, Armstrong’s seat was on the far left. He was sitting next to the abort handle, which he could twist if something went wrong with the Saturn and they needed to get out of there. Aldrin settled into the center seat and Collins sat on the right. Collins noticed that a pocket on Armstrong’s leg looked ready to snag the abort handle and alerted him. Armstrong moved it as well as he could.

A crowd of more than a million people showed up to watch. Some of them had camped out for days. To get out of the worst of it, Armstrong’s family watched from a yacht in the Banana River. “I haven’t aged a day,” Janet Armstrong joked to the yacht’s captain when he asked if this sort of thing wasn’t stressful for her. She decided to save her celebration for the day the crew splashed down.

A crowd of more than a million people showed up to watch. Some of them had camped out for days. To get out of the worst of it, Armstrong’s family watched from a yacht in the Banana River. “I haven’t aged a day,” Janet Armstrong joked to the yacht’s captain when he asked if this sort of thing wasn’t stressful for her. She decided to save her celebration for the day the crew splashed down.

At 9:32 am EDT, Apollo 11 launched. Records show that the heart rates of all three crew members went up in anticipation of what they were about to do, with Armstrong’s the highest at 110 beats per minute. The noise was deafening at first but fell steadily after thirty seconds. Then, the first stage burned out and fell away, and the ride smoothed out. Twelve minutes after launch, they achieved orbit and began checking equipment as they prepared for the Trans-Lunar Injection (TLI) burn that would put them on a course for the Moon.

To The Moon

The checkout went smoothly, and the first sunrise was so spectacular that they wanted to get a picture of it. This led to a hunt for a missing Hasselblad camera that they finally corralled, too late to get the picture but well in time to keep it from doing damage during the TLI. At two hours and fifteen minutes into the flight, they received the go for TLI and put their helmets and gloves back on. This was supposed to protect them during the burn but Armstrong thought it would have hampered their ability to react to an emergency.

The checkout went smoothly, and the first sunrise was so spectacular that they wanted to get a picture of it. This led to a hunt for a missing Hasselblad camera that they finally corralled, too late to get the picture but well in time to keep it from doing damage during the TLI. At two hours and fifteen minutes into the flight, they received the go for TLI and put their helmets and gloves back on. This was supposed to protect them during the burn but Armstrong thought it would have hampered their ability to react to an emergency.

The burn went smoothly and the Saturn’s job was done. Michael Collins took control of the Columbia to separate it from the rocket. Then, he turned around to retrieve the Lunar Module, which they had named the Eagle. The Eagle was secured in a compartment on the Saturn to protect it during launch and this was where all the work on docking during the Gemini program came in handy. The maneuver went well though Collins had gone out a few feet more than he had planned while separating from the rocket. “Well, that wasn’t the best job I’ve ever done,” he told his crewmates. “Seemed fine to me,” answered Armstrong.

They could finally change out of their uncomfortable spacesuits and enjoy the ride. They didn’t really get an impression of speed because there was nothing outside to compare the position of their spacecraft to except the receding Earth and approaching Moon. Collins set the Columbia to do a slow roll to keep any point in the spacecraft from getting too hot or cold. It was tricky to get a perfect, rotisserie-style roll without any pitch or yaw action, but soon, they were getting alternating views of the Earth, sun and Moon through their window. They did some sight-seeing through a monocular and Armstrong described landmasses and weather patterns he recognized for the people back home.

They raided the pantry for their first meal in space. They could make sandwiches with tubed spreads that included ham, tuna, chicken salad and cheese or squeeze hot and cold water into packets of freeze-dried foods. Armstrong’s favorites included the spaghetti with meat sauce, scalloped potatoes, pineapple fruitcake cubes, and grape punch for the drink. They did have a grapefruit-orange citrus drink on board but Armstrong later went on record as saying that he didn’t think it was Tang.

After the meal, Collins settled into his seat to take the first watch while Armstrong and Aldrin pulled out mesh hammocks. They had fought drowsiness since before the TLI, leading Collins to quip, “You need to get out the alarm clock.” Adrenaline had kept them awake until this point and, even though it was beginning to wear off, they only managed to sleep for five and a half hours. They were already alert when Capcom Bruce McCandless gave them a wake-up call and the morning news. America was enthusiastic about their launch but the Soviets apparently weren’t. In one last act of defiance, they had launched a lunar probe called Luna 15. NASA was concerned that it might interfere with their mission but it would ultimately crash-land on the moon.

During the second day, there wasn’t much to do except some routine chores and an ultimately unsuccessful telescope experiment in which they tried to pinpoint a laser beam coming from an observatory near El Paso, Texas. Armstrong and Aldrin decided to check on the Eagle a day early to make certain it had taken no damage during the launch. They did have a bit of excitement when they saw a twinkling light outside their spacecraft. None of them could figure out what it was, and they didn’t want to tell Houston they were suddenly seeing UFOs. Armstrong radioed back, asking how far the Saturn was from them. The Capcom had to confer with somebody, and then answered, “It should be about 6,000 nautical miles away from you.” Armstrong thanked them and the crew decided it was probably one of the panels from the housing that had protected the lunar module.

They put on a live TV show for the Americans watching back home. It started out with Armstrong aiming the camera back at Earth and describing the view, and then Collins turned the camera upside down. “Okay, world, hang on to your hat. I’m going to turn you upside down.” Aldrin did a few push-ups and Collins demonstrated how to make chicken stew in zero G. Armstrong did a headstand and Collins quipped, “Neil’s standing on his head again. He’s trying to make me nervous.”

On July 19th, they got their first close-up view of the moon. The moon was between them and the sun, making for some interesting back-lighting. The Apollo 11 crew were being treated to their own, personal solar eclipse. They tried to get pictures, but no camera had yet been made to handle such unique lighting conditions and the quality of the pictures suffered for it. Collins thought the moon looked forbidding, while Armstrong described it as “a view worth the price of the trip.”

To make it into lunar orbit, the Columbia had to slow down with a precise engine firing called LOI-1, the first Lunar Orbit Insertion. The burn lasted six minutes and slowed their speed by 2,000 miles per hour. If they made a mistake, they could end up stuck in solar orbit. The burn lasted until they had swung behind the moon, making for some finger-biting nervousness back at Mission Control. For the first time, they didn’t have radio communications. Twenty-three minutes later, they reestablished contact: “That was a beautiful burn!”

They spent some time just looking down at the moon, picking out landmarks and debating about what color it was. Collins thought it looked like Plaster of Paris, light grey, and so did Armstrong at first. Then, it turned tan. The angle of the sun was making the difference. It looked different at “noon” than it did at “dawn” or “dusk.” Armstrong picked out the planned landing site and radioed back to Houston, “It looks very much like the pictures, but like the difference between watching a real football game and watching it on TV. There’s no substitute for actually being here.”

The crew reluctantly got in one last live TV show. They pointed out the planned route the Eagle would take and landmarks like Apollo 8′s “Mount Marilyn.” The Sea of Tranquility looked dark; Collins would later describe it as “distinctly forbidding.”

They made a seventeen-second burn to alter their orbit from a 168.8-by-54.4-mile ellipse to one that was 66.1 by 54.4 miles. That came within a few tenths of a mile of what they planned on and they were thrilled at the precision. Armstrong and Aldrin went to the Eagle for one last systems check. With a big day ahead of them on July 20, they hit the sack. Perhaps the adrenaline was beginning to kick in again and none of them got a lot of sleep.

The Landing

July 20, 1969

This morning, every American who could watch was glued to a television set for the live coverage. There had been telecasts about the symbolic and spiritual meaning of the first landing. Nervous NASA and White House staffers had prepared statements in case Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin never made it off the moon. Armstrong and Aldrin were certainly so excited that the routine they had worked out for previous mornings in space “came unglued,” as Aldrin put it. Still, they managed to get breakfast together and then changed into the suits they would wear on the moon.

The Russians had dubbed Armstrong “The Czar of the Ship” and he was so quiet while they were checking out the Eagle that Collins asked, “How’s the czar over there?” Armstrong answered, “Just hanging on and punching [buttons].” As the minutes ticked down to the undocking, Collins told them, “You cats take it easy down there. If I hear you huffing and puffing, I’m going to start bitching at you.” Then he threw the switch to release the Eagle.

There is no video of the Eagle pulling away from the Columbia because Collins told Houston there was no room for a video camera at the window. Armstrong rotated the Eagle so Collins could get a good look at its bottom and make sure the landing gear was in position. “Looks like you’ve got a good looking flying machine there, Eagle, despite the fact that you’re upside down,” he told them. “Somebody’s upside down!” Armstrong joked back.

They began their descent with an engine firing called Descent Orbit Insertion (DOI). This was designed to drop their orbit to an altitude of 50,000 feet. Armstrong and Aldrin both kept an eye on their navigation systems. Their primary navigation was called the Primary Navigation, Guidance and Control System (PNGS), a digital computer that processed information from an inertial platform. The second, backup system was called the Abort Guidance System (AGS) and could be used if they had to return to the Columbia without landing. It used body mounted accelerometers for measurement. Apollo 10′s Lunar Module had run into problems with their navigation systems, causing it to go into some wild gyrations. That was the sort of thing they had to avoid.

They could only estimate their altitude at this point. The Eagle wasn’t oriented to use radar yet and it would have been inaccurate at this point anyway. The window that the Mercury astronauts had fought so hard to have included in spacecraft came in handy in situations just like this. Armstrong could eyeball the lunar surface and use the Eagle’s angular rate and velocity to make on-the-fly calculations about altitude. He came up with a figure of about 53,000 feet, within a few thousand feet of what the computer was saying, and received a “Go” for powered descent from Houston.

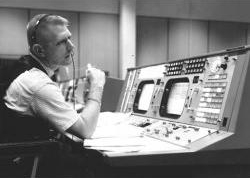

They activated an exterior camera that would allow Earth to watch the powered descent. The people waiting on the ground were tense even if the astronauts weren’t. Wally Schirra was acting as commentator for Walter Cronkite’s telecast and asked if he had thought about what he would say when they landed. The normally articulate Cronkite didn’t have an answer ready. Perhaps some listeners noticed that Aldrin seemed to be doing the talking for both of them as they approached the surface. Armstrong was completely focused on the job.

He adjusted the Eagle’s attitude so that the radar antenna was pointed at the moon. It turned out to be a good thing he did. The radar showed that they were almost 3,000 feet closer to the surface than the PNGS has indicated. While they rolled into an upright position, they got a magnificent view of a marble-sized Earth and then were able to pick out landmarks on the Moon. They were traveling down what had been dubbed “U.S. Highway 1″ in honor of the pre-Interstate Highway System road.

Then, a yellow light came on and Armstrong checked it. “Program alarm. It’s a 1202,” he told Houston. A 1202 error meant that the computer was receiving more data than it could handle at any given time. Eyebrows must have gone up in Mission Control. In one of the simulations they had run just before the mission, somebody had mistakenly called an abort on this exact same alarm. “We’re Go on that alarm,” Capcom told them. The 1202 light would flash two more times in the next four minutes, and then they got a 1201 error. “We’re Go. Same type. We’re Go,” Capcom told them.

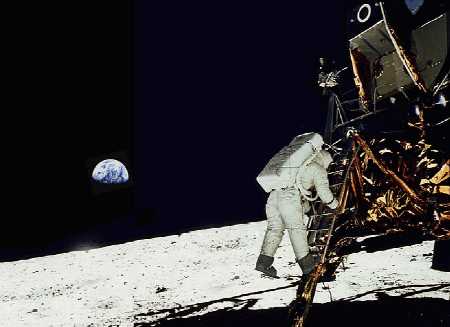

They were getting close to the surface and, though Armstrong had studied images from automated lunar orbiters, he didn’t recognize any of the landmarks. They were approaching 500 feet above the surface. He didn’t like the look of the boulders, some of which were the size of Volkswagens, so he took manual control of the lunar module to look for a more open area. Aldrin kept a careful eye on fuel, as did the people in Mission Control. At one point, Aldrin warned him, “Quantity light.” The fuel level dropped below 5 percent of their original load. They were approaching the point where they would either have to commit to landing, or abort. Armstrong finally spotted a good place and began the final descent, kicking up some dust. They landed with thirty seconds of fuel to spare.

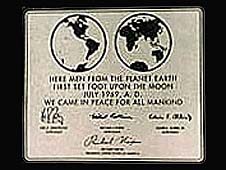

Armstrong reported, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Capcom was so excited that he stammered a bit, “Roger, Twan… Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You’ve got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

The EVA

There were still a few issues that might prevent them from staying on the Moon. One of them was the issue of mascons, “mass concentrations,” that were believed to be deposits of very dense matter. Another was the fact that their landing area was on the sunlit side of the moon. Temperatures could get high enough to overheat the hydraulics system and cause pipes to burst. They solved that problem by venting the fuel and oxidizer tanks. The mission rules included three Stay/NoStay times. T-1 was two minutes after the landing and T-2 was eight minutes after T-1. T-3 would come two hours later, when the Columbia was overhead again. In case something went wrong and they had to get out of there, they went through most of the procedure of a normal takeoff to make certain everything worked okay.

There were still a few issues that might prevent them from staying on the Moon. One of them was the issue of mascons, “mass concentrations,” that were believed to be deposits of very dense matter. Another was the fact that their landing area was on the sunlit side of the moon. Temperatures could get high enough to overheat the hydraulics system and cause pipes to burst. They solved that problem by venting the fuel and oxidizer tanks. The mission rules included three Stay/NoStay times. T-1 was two minutes after the landing and T-2 was eight minutes after T-1. T-3 would come two hours later, when the Columbia was overhead again. In case something went wrong and they had to get out of there, they went through most of the procedure of a normal takeoff to make certain everything worked okay.

Everything looked fine, and they received the Stay decisions for T-1 and T-2. They continued systems checks until after T-3, and then Armstrong took advantage of a free moment to look outside. The area looked like it had gotten pummeled by several truckloads of pebbles, with miniature craters ranging from one foot to fifty feet across. There were a few ridges between twenty and thirty feet high and a hill that Armstrong estimated was about a mile away. Everything appeared to be various shades of grey.

The plan was for the first Moonwalkers to take a four-hour nap before the EVA. They were too excited to sleep and Armstrong gave up readily enough: “Okay, let’s get on with it.” They ate a planned meal and did some housekeeping chores, and then donned gloves, helmets and backpacks for the trip outside. They had to watch it because a stray elbow could have damaged the thin walls of the Eagle. They did damage a circuit breaker they needed for liftoff and Aldrin was able to solve the problem later using a felt-tip pen. As it turned out, it was pretty cramped in the Lunar Module with their suits on and it was very possible that Armstrong would have had to be the first out anyway.