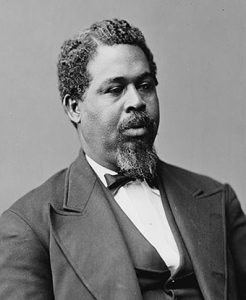

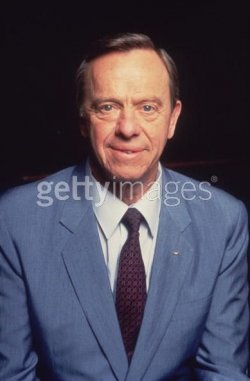

Alan Shepard

One of the most complex of the Mercury astronauts, Alan Shepard was the first American in space and the fifth man to walk on the moon. In between, he worked closely with fellow Mercury astronaut Deke Slayton to take charge of the Astronaut Office and overcame an ear condition that nearly ended his career as an astronaut. He also become known as the “Ice Commander” among his peers for his cool, icy attitude and “Smilin’ Al” for his ability to become a hard-charging party animal.

One of the most complex of the Mercury astronauts, Alan Shepard was the first American in space and the fifth man to walk on the moon. In between, he worked closely with fellow Mercury astronaut Deke Slayton to take charge of the Astronaut Office and overcame an ear condition that nearly ended his career as an astronaut. He also become known as the “Ice Commander” among his peers for his cool, icy attitude and “Smilin’ Al” for his ability to become a hard-charging party animal.New Hampshire Roots

East Derry, in southeastern New Hampshire, was a small town with families that had been rooted there for centuries. The Shepards were one of those families who could trace their North American lineage to the 1690s. They were hard workers and, thanks to Alan Shepard’s grandfather’s successful businesses, part of the upper class. Shepard was no spoiled rich kid, though. His father, Bart Shepard, served in the National Guard and then the Army Reserves and so proud of his military service that he insisted that his children call him “Colonel” or “Sir”. Bart Shepard made sure his children took on their share of chores. For young Alan Shepard, this meant hauling ice blocks for the ice house that preceded refrigerators and also delivering newspapers. Alan Shepard inherited both his work ethic and his large eyes from his father.

His sense of fun came from his mother, Renza Emerson. She was a Christian Scientist, a faith that Alan Shepard would inherit, and believed in the power of positive thinking. She enjoyed gardening and tobogganing in their proper seasons and taught her son to be assertive.

Most of the other boys in town would remember him as someone who could be friendly one day and barely acknowledge them the next. He wasn’t an introvert; he just didn’t have any close friends. Others his age were people he could have fun with but he didn’t particularly need their approval. This tendency would follow him for most of his life.

He developed a mischievous streak that later established him as the second-best pranster of the Mercury astronauts, behind only veteran joker Wally Schirra, when he wasn’t being the Ice Commander. Even early on, his idea of a joke was to give his uncle an exploding cigar. The Shepards were apparently a sober bunch; the only ones who laughed were Alan Shepard and his uncle Fritz, the victim of the joke.

Exploring his grandparents’ basement, he discovered the tools that his grandfather had left behind and also an old cider press. He would gather apples that fell to the ground, run them through the press, and let the cider ferment for a few weeks. Then, he would share the results with a few other boys. Probably the only reason he got away with it was that his grandmother was hard of hearing.

The tools were part of a workshop his grandfather had used to tinker with technological items like radios and an old phonograph. Shepard dusted them off and spent many hours in his grandparents’ basement, learning how to rebuild small engines and creating a small flotilla of model boats from scraps of wood.

He initially did well in school, skipping the sixth and eighth grade, but hit a bump when he reached high school. He was the smallest one there and had to work harder than most to keep up. During the summer after his freshman year, he swam in a local pond to build up his muscles. He gained a reputation for being astonishingly ambitious, often competing fiercely with others to get what he wanted.

He also developed a fascination with flying, fueled partly by reading Charles Lindbergh’s autobiographical book about his aerial adventures, simply titled We. The ceiling of Shepard’s room was quickly decorated with a collection of balsa-wood airplanes. His first attempt to fly in a glider borrowed from a friend was a failure. A gust of wind caught the wing at the wrong moment and flipped the glider upside down. His friend would sum up the results in a single word years later: “Matchsticks.”

The failure hardly discouraged Alan Shepard and, in early 1938, he talked his mother into taking him to Manchester Municipal Airport for his first airplane ride in an early commercial plane called the DC-3. He enjoyed it so much that he tended chickens and sold the eggs so he could earn money for a bicycle. The experience taught him the rudiments of busiess. It took him nearly a year to earn enough and he rode that bicycle to the airport every chance he got. He traded work for flying lessons and his teacher called him “a natural.”

During his final year in high school, Shepard began thinking about his future. His father suggested West Point. Shepard wasn’t thrilled at the idea of going into the Army, so he chose the Navy, which would give him a chance to fly with some of the most daring fighter pilots around. He would almost blow that chance before he ever laid a finger on a Navy plane.

The Naval Academy

Being a freshman plebe at the Naval Academy was not easy. Chores included shining upperclassmen’s shoes until they shone, memorizing the day’s menus for “chow call,” and waking half an hour before the upperclassmen so that they could close windows. The upperclassmen would heap insults and humiliations on plebes like Shepard.

Shepard fought back. When upperclassmen forced him to dive under the table in the mess hall, he would try to smear butter on their shoes. Once, he led a group of plebes in hiding the left shoes of all his tormentors. Getting caught meant getting caned or receiving a few demerits, but he was often able to talk his way out of trouble. The upperclassmen would remember him as an annoyingly charming and unbreakable young man.

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the Acadamy decided to move Shepard’s class’s graduation date up a year to 1944. This meant that Shepard would get a chance to enter the war. That was still three years in the future and his grades were dismal. He goofed off so much that officials issued an ultimatum: “Shape up or face expulsion.” He would owe the Navy some time in the service either way, so he concentrated on improving his grades. That didn’t end his hijinks. He never could resist a ritual called going “over the wall.” He would slip out and into the nearby Annapolis, where he and other midshipmen could meet up with girls. It was not so different from a jailbreak. Students risked demerits if they left the dorms when they were supposed to be sleeping but that didn’t stop Shepard.

He met his future wife, Louise Brewer, at a Christmas dance. She already had a boyfriend, but he asked her to dance anyway. Shepard quickly realized that she was different from all the other girls and kept thinking about her. They would exchange letters and sometimes attend dances together for the next two years.

The glow of that first meeting would fade abruptly when Shepard heard of his cousin’s death. Eric was training to be a Marine aviator and the plane he had been training in had crashed. It was ruled an accident but there were rumors that he had been showing off and lost control. Shepard got leave to go to the funeral. The death of his cousin hit him hard and reminded him of his goal to be a Navy fighter pilot. He returned to the Academy and threw himself into his studies. A training cruise before the start of his senior year was enough to convince him of his choice but, upon graduation, he still had to put in a year at sea before the Navy would consider training him as a pilot. It would be a long year.

U.S.S. Cogswell

Shepard graduated from the Naval Academy, proposed to Louise Brewer, and headed out to San Francisco to catch the Holbrook, an old freighter that would take him out to the U.S.S. Cogswell. It took weeks for him to arrive, during which the crew mistook a whale for a submarine and the Holbrook was damaged in a collision with another ship. During a stopover at Biak Island, Shepard got a chance to fly with a B-25 bomber and watched the gunner strafe a few straggling Japanese airplanes. It only whetted his appetite for flying.

The Cogswell was a destroyer that would be assisting efforts to establish military bases on islands recently captured from the Japanese. Shepard was assigned to the internal phone circuits, a boring job for an aviator-to-be. They were traveling with the U.S.S. Reno when a torpedo slammed into the Reno, tossing men overboard. The rest of the damaged ship’s crew jumped overboard and the Cogswell rescued 172 sailors, some of them classmates Shepard recognized. Reno limped to safety with Cogswell providing escort. The Cogswell went on to survive typhoons and thwarted kamikaze attacks and also helped hunt down submarines. The crew earned a unit citation for aiding the Reno and Admiral “Bull” Halsey of the Third Fleet praised their courageous actions.

Shepard was unable to make it home for his grandmother’s funeral just before Christmas of 1944. The Cogswell pulled into San Francisco for an overhaul in late February 1945 and Shepard got a few weeks’ leave with most of the rest of the crew. He used the leave to head home and marry Louise Brewer. The honeymoon was too brief and Louise moved into a San Francisco apartment with a college friend to wait for Alan Shepard’s return. While there, she made friends with several other military wives and often attended parties with them.

Meanwhile, Shepard was promoted to deck officer and put in charge of several anti-aircraft guns on the ship’s bow. He would be helping watch for kamikazes. The ship’s new skipper was a foul-mouthed disciplinarian who often called Shepard to task for pranks or ignoring his duties to watch planes take off and land on nearby aircraft carriers’ decks. Another crew member would later comment that Shepard was simply “on the wrong ship.”

Germany surrendered, but fighting was still vicious in the Pacific. During duty in “Kamikaze Alley,” the Cogswell sailed right into the thick of the action with bombs and kamikazes everywhere. The sound of the 20- and 40-millimeter guns going off was deafening. Many of the crew members were convinced they wouldn’t survive until morning. They made it, nailed a few kamikazes, and one sailor put it in a rather understated way: “The kamikazes raised hell last night.”

Others weren’t so lucky. The Cogswell saw plenty of the results of kamikazes, including destroyers that had been damaged so badly that they had to be towed. For a while, it must have seemed like Shepard couldn’t turn around without receiving word that one of his classmates from West Point had been killed. The Porter sank though Cogswell and the other ships of the convoy managed to rescue the crew. The Pringle went down and one survivor who had jumped overboard reported that he could hear the screams of the crewmen trapped on board. The Japanese refused to surrender in the face of certain defeat and it took two atomic bombs to end the war.

Cogswell was part of the fleet sent to Tokyo Bay to prepare for surrender ceremonies. Many of the sailors wondered if it was really over. The Japanese had earned their respect as ferocious fighters and they would not have been surprised if some of their recent enemy simply refused to give up. For the rest of his life, Shepard remained reluctant to speak of his World War Two experience. In mid-September, he received the orders he had hoped for. He would report to Corpus Christi for flight training.

Shepherds of the Sea: Destroyer Escorts in World War II

This book describes WWII-era Destroyers and their actions in the war, from the stories and personal diaries of the men who lived through it.

Corpus Christi

The heat was one of the first things new cadets noticed about Corpus Christi. It had been a fairly typical border town before the military decided to plant a training facility for future aviators there and it was nothing unusual to see cadets faint while taking part in any activity that took them outside. Being indoors was no guarantee of relief, either. Air conditioning was still not common.

For those devoted to a life of flying, Corpus Christi was paradise, albeit a risky one. As enthusiastic as Shepard was, he received his first lesson in how dangerous flying could be only two weeks after his arrival. He was in class when the crash siren sounded. Two planes had collided in mid-air, killing twenty-two out of the twenty-seven people on board. Shepard would hear stories of tragedies that happened because a novice was inattentive or swerved the wrong way and see wreckage displayed by the staff as a reminder of the dangers of flying.

Most students in Shepard’s class learned the basics of flying in a yellow Stearman N2S nicknamed the Yellow Peril. It made use of a simple stick-and-rudder system and a one-way rubber tube that instructors used to communicate with their students. Once they mastered the Yellow Peril, they could move up to the Valiant and the PBY seaplanes. They also had to prove their proficiency in a series of check flights. Each maneuver could be rated “good,” “satisfactory,” “borderline,” or “unsatisfactory.” If a student earned too many “unsatisfactory” ratings, it was usually a sign that he would wash out of the training program. During Shepard’s first check flight, he rated seventeen “satisfactory” ratings out of twenty-four maneuvers, with one “good” and five “borderline.”

Perhaps his instructor was being generous, because his marks plummeted when he passed on to the next stage of training. Some instructors at Corpus Christi felt that it was their self-assigned duty to weed out slackers and uninspired fliers. Shepard’s first solo was sloppy and comments from his instructors noted that he relied on instruments too much and often seemed disoriented. It got so bad that he faced the same problem that he had at West Point. He would have to either improve his flying, or return to the regular Navy.

Finally, he stepped back, analyzed the problem, and concluded that he simply needed more flying time. There were never enough working planes to go around due to a mass exodus of mechanics and he could go up to eight days without a flight. Though officers at Corpus Christi disapproved of private lessons, Shepard went behind their backs and signed up. Within a few months, he earned his private license and his flying showed a significant improvement. Years later, he admitted to a reporter that his problems at West Point and Corpus Christi were fundamentally the same. He had gotten complacent, and complacency was his worst enemy.

After nearly a year at Corpus Christi, Shepard attempted what amounted to a final exam. He would try to make six perfect landings on an aircraft carrier. This kind of landing is so difficult that he would later dare pilots from other branches of the military to try landing on an aircraft carrier whenever they started bragging about their flying. His only help would be signals from a landing signal officer (LSO), who could use paddles to signal him to adjust his approach or abort and try again. This could be a nerve-wracking experience for the LSO. If something went wrong, he would have to jump off his platform fast or he would get smeared. Shepard made all six of his landings flawlessly with his father watching. Bart Shepard awarded him with the gold wings that marked him as a true naval aviator.

Corsairs

After his graduation into the ranks of naval aviators, the Navy asked for his preference for assignments. Carrier aviation was at the top of Shepard’s list and he added a request for an assignment that would have him flying Corsairs. Only the best aviators could handle the tricky F4U Corsairs and they had a reputation for being kamikaze-killers. The combination was irresistible to Shepard. He received an assignment to a fighter squadron based near Jacksonville, Florida.

He quickly got a lesson in how dangerous flying Corsairs could be. The Corsair could stall at slower speeds and flip to the right, often resulting in a crash. This happened to one of Shepard’s classmates when he was coming in for a landing, resulting in a bad fireball. Corsair pilots had to learn how to cope with deaths among their comrades and, for many, coping was assisted by a stiff drink. That method of coping was not always appreciated by the locals or senior officers. Two of Shepard’s friends got themselves kicked out of a beach house they had rented due to their booze-driven parties. Perhaps the landlord had been tipped off by a vice admiral who lived just down the street and had ordered them to quit without much success.

Louise was pregnant with their first child by this point. Pregnancy did not agree with her. She was confined to her bed and finally gave birth to a healthy daughter named Laura. After recuperating at her parents’ house, she rejoined Alan Shepard, who had just been reassigned to a squadron in Virginia. Fighter squadron VF-42 was based on the U.S.S. Franklin D. Roosevelt, which was currently being overhauled. He quickly became Wing Commander Doc Abbot’s wingman, responsible for watching his leader’s “six o’clock.” Once the overhaul of the FDR was complete, they were assigned to a few-month tour of the Caribbean and then to the Mediterranean, where they would be assisting efforts to fly supplies into the Soviet-blockaded West Germany.

On the way to the Mediterranean, they ran into a storm so bad that they lost all their Corsairs. It was enough to make Shepard sick. They soon got replacements, though, and they spent most of their actual flying time putting on air shows for visiting dignitaries like King Paul and Queen Frederika of Greece. In the meantime, Shepard worked his way up to commanding a division of four planes, with a corresponding jump in his ego. He maintained the charm that had helped him worm his way out of trouble at West Point and his fellow pilots would describe him as one of those people who was either liked or hated by others. There was never any in-between.

Inevitably, Shepard became bored with air shows and set his sights on test pilot school. Abbot was transferred to the Pentagon, which gave Shepard exactly the opening he needed. He sent Abbot a letter with his request. While waiting for a reply, he met Turner Caldwell, who was famous for commanding one of the Navy’s first night flying squadrons and then breaking a speed record in the Douglas Skystreak two months before Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier. Shepard lapped Caldwell’s flying stories right up until he got transferred to an assignment that would make all his peers jealous. He was going to the test pilot school at Patuxent River Naval Air Station, known throughout the fleet as Pax River.

Whistling Death: The Test Pilot’s Story of the F4U Corsair

Test pilots like author Boone T. Guyton were always looking for ways to improve military planes like the Corsair. See how this plane was developed from a test pilot’s point of view.

Pax River

Alan Shepard was again the youngest in his class at twenty-six years old. Many others grumbled about it, believing that Shepard had used his ability to make connections, rather than his flying skill, to get into Pax River. Shepard didn’t deny it. In any case, his connections would save him from a court-martial.

Flat-hatting was a risky pilot tradition. Pilots would swoop down on a target and pull out of the dive at a low enough altitude to be terrifying. One legend had it that flat-hatting got its name from a pilot who swooped so low that he actually flattened a man’s hat. Variations included hedge-hopping, in which pilots would chase livestock through a pasture. A pilot could get in trouble for it, but only if he was caught. Many of Shepard’s contemporaries were hard-pressed to explain why there were telephone wires hanging from their planes and there were a few fatal accidents.

Shepard’s flat-hatting at Pax River was one way he could let Louise know he would be home soon. He would get as low as one hundred feet and an admiral told him to quit when they got complaints from a local turkey farmer. He earned a reputation for being a meticulous test pilot besides that, and officials began to trust him with more complex assignments.

His ego swelled with his responsibilities and he once again demonstrated his ability to nearly sabotage his own career. He took his flying antics to a whole new level and decided to loop the half-finished Chesapeake Bay Bridge. He was caught and received a stern reprimand. Somebody filmed him flat-hatting along the beaches of Ocean City, low enough to blow bikinis off sunbathing women. He received a letter of reprimand and also had to pay a visit to the local sheriff’s office to convince them not to press charges. But these two warnings apparently weren’t enough.

Chincoteaque Island in Virginia requested a test pilot to help with high-altitude tests of the F2H-2 Banshee and Pax River sent Alan Shepard. He successfully performed the test, which involved climbing to an altitude of 50,000 feet and firing a missile, and prepared to fly home. After takeoff, he radioed the tower for permission for a low pass, a pilot’s way of showing off after a successful mission. Most of the men had gathered on the tennis courts for an inspection and Shepard found it irresistible. He flat-hatted down to 150 feet above the tennis courts, sending men scrambling for cover. The base commander was furious. When he returned to Pax River and saw Admiral Pride with a scowl, he knew he was in for it.

Pride wanted to court-martial Shepard but his immediate supervisors managed to talk him out of it. As a compromise, they grounded Shepard, made him move into bachelor’s quarters for ten days, and made it clear that one more of those antics and he would be kicked out of the Navy. When his colleagues heard the story, they had to wonder exactly how many guardian angels he had watching over him.

The near court-martial failed to ruffle Shepard much and, in 1953, he left Pax River convinced that he was one of the hottest pilots around.

USS Oriskany

Shepard was assigned to a squadron on the USS Oriskany, which was on its way to Korea. During that time, the Navy was phasing out prop planes in favor of jets and Shepard got the job of introducing some F2H Banshees to his new squadron. The Oriskany wasn’t really designed for Banshees and Shepard had to teach them how to land without damaging the deck. The commander of Air Group 19, called “Jig Dog” Ramage, had earned the Navy Cross for his actions in World War II and took a shine to Shepard, who became Ramage’s wingman.

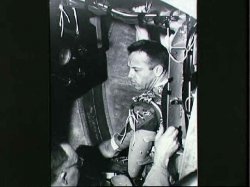

The armistice ended any chance Shepard had of seeing action in Korea. The Oriskany spent some time patrolling the Korean coast anyway. While flying a night mission, Shepard received a report from the Oriskany that some unidentified bogeys had been spotted. He intercepted them and they turned out to be Air Force planes on their own mission. On the way back to the ship, he flew into a blinding storm and had to resort to strictly instrument flying. He kept an eye on the homing signal that represented the Oriskany. The homing signal suddenly vanished as well as part of his control stick’s responsiveness. He guessed that his plane had been hit by lightning, frying much of his electrical system.

He tried calling the ship, “Malta Base, this is Foxtrot Two. Do you read? Over.” He could barely hear the reply: “Foxtrot Two, this is Malta Base. I can just barely read you.” He reported his situation and Oriskany asked, “Do you wish to declare an emergency?” That would mean he wasn’t on top of the situation, nothing that a fighter jock like Shepard liked to admit. He answered that he wanted to try a couple of things before declaring an emergency. He reached the place where he thought the Oriskany had been and flew in a search pattern until he spotted his ship’s lights.

Now he had a new problem. Landing on a carrier’s deck was like threading a needle at the best of times, and the storm had whipped up some wicked waves. It would be like trying to land on a bucking bronco. With only five minutes of fuel left, Shepard would only have one chance, and neither could he afford to worry about damaging Captain Griffin’s precious deck. He slammed down hard on the deck to make sure his tail hook did its job of snagging an arresting wire. He came to a stop and only much later did he admit that he had really been worried.

Soon afterwards, the Oriskany headed back to San Francisco. Shepard’s squadron practiced formation flying on the way back and he convinced his fellow pilots to try a tight diamond formation made famous by the Blue Angels. Like most typical Shepard stunts, this was completely against the rules without prior approval. They zoomed low over the Oriskany deck and everybody except Captain Griffin and Jig Dog were amused. Shepard was confined to his quarters for a week. As usual, he managed to talk his way back into Jig Dog’s good graces and even managed to wrangle permission to form his own stunt group, known as the Mangy Angels. It probably helped that, with Jig Dog, the only unforgivable sin was outright incompetence, and Shepard was never incompetent.

Jig Dog’s tolerance paid off during a planned mock attack on the U.S.S. Iowa. It was snowing heavily and they expected that the drill would be called off. It wasn’t and neither Jig Dog nor Shepard ever found out why. Jig Dog’s windshield froze over and he cranked the heat in the hope that it would thaw the ice. Then, he began to black out and veer off course. Shepard realized that Jig Dog was in trouble and called over the radio, “CAG! Nose down, CAG. Nose down. Wings level. You’re going in.” Jig Dog did his best to shake off the effects of oxygen deprivation and regained control. Shepard kept talking to him while he dropped down to a lower altitude and, when they returned to the ship, they discovered that a faulty oxygen system had nearly killed him. “I owe you one,” he told Shepard when they retreated to the ready room. He would get his chance to repay his wingman when an admiral wanted Shepard to become his aide. Jig Dog discovered that Shepard didn’t want the job and talked the admiral out of it. “He’s a hellraiser,” he told the admiral, which was not entirely a lie considering all the stunts Shepard pulled and then sweet-talked his way out of.

Aircraft Carriers at War: A Personal Retrospective of Korea, Vietnam, and the Soviet Confrontation

This is an award-winning overview of U.S. aircraft carriers’ contributions to wars in Korea and Vietnam, along with the Soviet Confrontation.

Edwards Air Force Base

Soon after the Iowa incident, Shepard was reassigned to Edwards Air Force Base as a test pilot. By this point, flying at Mach 1 or 2 was becoming routine and they were flirting, sometimes fatally, with Mach 3. One of the first supersonic jets was called the Tiger, which was literally faster than a speeding bullet. This could be a problem in combat, as one test pilot found out when his bullets smacked into the windshield and damaged an engine. Shepard was assigned to “wring out” another annoying problem. When pilots attempted to turn, the Tiger could go into reverse yaw, spinning uncontrollably in the opposite direction.

The fact that Edwards was an Air Force base meant that Shepard had to put up with taunts from Air Force pilots. He typically shot back about how he would like to see the Air Force people land on a carrier deck in exactly the same conditions he had faced on the Korean coast. He claimed he was the man who could prove that the problems with the Tiger weren’t mechanical. Naturally, he ran into trouble the very first time he flew a Tiger.

He flew the plane up to 60,000 feet and went into a dive, aiming for Mach 1. He had nearly made it when his engines flamed out. His plane plummeted and he watched the Sierra Madre ascend toward him through a frosting-up windshield. A lot of test pilots, convinced of their own invulnerability, would be in a heap of trouble at this point. He tried to restart his engines at 40,000 feet and 30,000 feet without any success. Finally, at 12,000 feet, he managed to get the engines restarted and he returned to base. He needed a couple of drinks to blunt the edge of the Air Force pilots’ taunts that time.

Shepard’s negative reports on the Tiger and, later, the F7U Cutlass would infuriate the manufacturers but save lives. By 1957, he became so respected for his ability as a test pilot that his superiors asked him to become an instructor. Individuals at the Pentagon began to think that he might make good admiral material if he could just curb his ability to find trouble. They sent him to the Naval War College in Rhode Island, which he considered a brief pit stop on his way to better things.

In the meantime, Louise’s sister died and they took in her five-year-old daughter. Alice remembered Shepard as someone who could be warm and loving but could also aim a frosty stare at her when he was angry. He spent his time in Rhode Island getting reacquainted with his family and getting to know Alice. Then, the Soviets pulled something out of the bag that would stun everybody.

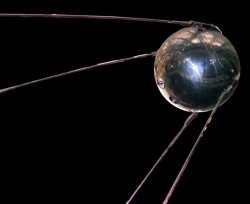

“That Little Rascal”

Sputnik caught most of America flat-footed on October 4, 1957. American leadership had received warnings that Russia might try something, most notably from the premier German-American rocket engineer, Wernher von Braun. Eisenhower’s administration had ignored the warnings and it cleared the stage for the Soviet Union to put the first artificial satellite into orbit. It was an international humiliation for the Americans that was compounded by Eisenhower’s timid handling of the situation.

Shepard slipped out of his house while the rest of his family was sleeping to see if he could spot Sputnik. He saw it twinkling in the southwest and muttered, “That little rascal,” to himself. He couldn’t believe that the technologically backwards Soviets could pull such a fast one on America. He would soon have the chance to help America rectify the situation.

NASA was created in the frenzy that followed Sputnik and Shepard soon heard that they were looking for experienced test pilots to become astronauts. He was positive that he would be invited but a junior officer misplaced his orders. When he finally received it, he could have strangled the officer if he wasn’t so elated. He headed straight to NASA’s temporary headquarters for a briefing. The men in charge of the selection process were positive that most would decline. In fact, some test pilots who hadn’t been invited were already making wisecracks about the whole thing. It was possibly a case of sour grapes and so many out of the first two groups volunteered that they didn’t need to call in the third group.

Shepard went on to the intense psychological and physical tests at Lovelace Clinic, never doubting for a second that he would be selected. His wife was more realistic, knowing that a total of 110 men were being considered. No one knew for certain what would happen to the human body in the hostile environment of space and Lovelace threw every test they could conceivably think of at the candidates. By the end of it, the candidates were calling the doctors “ghouls” and “sadists” and at least one of them stomped out. Shepard managed to keep his sense of humor through it all though coming up with twenty answers to the question, “Who am I?” nearly stumped him.

On April First, Shepard received word that he had been selected. The only one who was less than thrilled was his father, Bart Shepard, who felt that he was derailing his career. The elder Shepard would eventually come around and, for Alan Shepard, it was enough to know that he had “the right stuff.”

The Right Stuff

Though disliked by many of the astronauts for typical Hollywood-style inaccuracies, this movie focuses on the Mercury Seven and captures the spirit of the early Space Race-era space program.

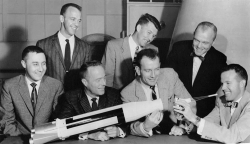

The Press Conference

The seven astronauts met for the first time shortly before the press conference on April 9, 1959. John Glenn was by far the most talkative of the group. He and Alan Shepard were nearly opposites and they would inevitably clash. None of them were used to the civilian suits they were wearing and Shepard couldn’t resist teasing Deke Slayton about the imaginary smeared egg on his bow tie.

John Glenn had the most experience with dealing with the press due to his record cross-country flight. He joked with the reporters and even managed to deftly fling one question back in their faces when asked about the tests at Lovelace Clinic: “Which one would you like the least?” The rest realized that they had better improve their ability to deal with the press, and quickly. They would need it, because interest in the seven new astronauts would go up like one of the rockets they were preparing for manned space flight.

Setting Up Shop

The press seemed determined to turn these seven men into superheroes and they hadn’t done anything yet. Their families got ambushed by reporters so often that one of NASA’s Public Relations people compared it to “being pecked to death by ducks.” They came up with an ingenious solution. Official NASA information would remain available to any reporter who asked, but the astronauts’ personal stories could be sold to the highest bidder. A lawyer named Leo D’Orsey took on the job and Life magazine bought the rights for $500,000, to be divided among the astronauts. This cut down on the invasion of the astronauts’ private homes and helped Alan Shepard jump-start his way into a series of successful business ventures.

Shorty Powers also joined NASA’s public relations people as chief of public information. He tried to teach the Mercury Seven how to deal with the press effectively, but felt from the start that the astronauts were out to make his life miserable. In turn, at least one of the other astronauts described him as “a real pain in the ass” who was way too fond of “the freedom of the press thing.” Powers did manage to help Shepard become a better speaker at the press conferences and it wasn’t long before Shepard and Glenn got into a competition to see who was the best with the reporters.

They tried to work out a compromise with “the freedom of the press thing” that involved making the astronauts harder for the Life people to find, but they forgot to factor in the cleverness of one photographer named Ralph Morse. During survival training, Shepard and fellow astronaut Wally Schirra were out in the Nevada desert when Morse found their camp and pulled up in a Jeep. Morse apparently didn’t realize that he had just found the two biggest jokers among the astronauts. They rigged Morse’s Jeep with a smoke flare and then told him, “Your Jeep is in the way. You’d better move it.” When he tried to start it, the flare went off, covering him with smoke and ruining the Jeep.

NASA decided that Langley Air Force Base would be the central hub for the astronauts and most of them moved their families to the area. It became little more than a place for the astronauts to make a pit stop for necessities as they dived more into their training and duties. They started out with a few-week classroom course with the engineers who were working on the rockets and would be designing their spacecraft. This gave them a chance to get to know each other. Shepard often came off as an aloof and icy man with no close friends, who nonetheless knew how to have fun when he allowed himself to relax. He saw John Glenn as the other top flier of the seven and wondered how two top test pilots could be so different. It showed in their choice of cars, a flashy sports car for Shepard and a sturdy, gas-saving Studebaker for Glenn. Glenn was a solid family man, practically a Boy Scout, and Shepard was a smoking, drinking skirt chaser. Both were fiercely competitive, though, and both wanted to be first. It was little wonder that there would be friction between them.

The frequent rocket mishaps did little to inspire the astronauts. The branches of the military were competing for the right to design rockets for the space program and they tried a test launch of the Air Force’s Atlas. They watched it explode from only a quarter mile away. Shepard’s reaction was classically deadpan: “I’m glad they got that one out of the way. I sure hope they fix that.” Considering that explosion, it was no surprise when NASA decided to go with Wernher von Braun’s less powerful but more reliable Redstone for the first two manned launches.

As brilliant as Doctor von Braun was, his Redstones weren’t perfect, either. They got a lesson in how important details can be when a cord that was a few millimeters too short caused a premature engine shutdown during one test. Shepard’s response: “What do you expect from rockets built by the lowest bidder?”

They learned from their mistakes and NASA hinted that the first space flight could occur in a year. The astronauts dived into an intense training course that included sessions in the centrifuge and the MASTIF. Shepard had the most trouble with the MASTIF, which could simulate an out of control space capsule by spinning on all three axes while the astronaut tried to stabilize it. This was enough to make anybody dizzy and Shepard had to hit the “chicken switch” the first few times he tried because it made him nauseous. When he was later diagnosed with Ménière’s disease, NASA doctors would wonder if that had been the first sign of trouble. He was no quitter, though, and he kept at it until he was able to stabilize the MASTIF without trouble.

It wasn’t all work for the astronauts. They could unwind with highly competitive games of cards and handball. They also raced cars except for Glenn and his Studebaker, which they made fun of. The cars were fair game for any number of gotchas, which ranged from hiding dead fish in the back seat to “tweaking” their performance with help with a friend who was a car dealer. Alan Shepard and the others received a recording of comedian Bill Dana and his cowardly astronaut character named Jose Jimenez. Shepard loved it so much that, when his flight in Freedom 7 rolled around, Jose Jimenez provided a little comic relief over the communication loops. Whenever Bill Dana came to town, the astronauts would pay him a visit and join him onstage as straight men.

Cape Canaveral

During the summer of 1960, NASA moved its base closer to Cape Canaveral. The astronauts set up shop there soon afterwards and promptly discovered a seedy town named Cocoa Beach. They quickly decided that it was no place for their families and left them in Virginia. Before NASA personnel settled there, Cocoa Beach’s most prominent features were the bars. This was perhaps a little too attractive for a few of the astronauts and reporters soon learned that the best place to find an astronaut was in a bar. Walter Cronkite remembered getting Shepard to open up by having a drink or two with him and revealing that he had flown in B-17 bombers during World War Two.

A favorite was the then-solitary Starlite Motel, where Henri Landwirth was the manager. Landwirth treated the astronauts like family and the fact that they were frequent guests meant that the Starlite Motel was often booked solid with reporters and others who wanted to be around them. When Landwirth moved to a new Holiday Inn, the astronauts followed. The astronauts did not lose any of their exuberance when they stayed at his hotel and a less tolerant innkeeper would have kicked them out. But, like Shepard had at West Point, Landwirth learned to fight back in a humorous way whenever they gave him a hard time.

Glenn would frequently warn his colleagues that their exuberance could get them into trouble, especially when they crossed the line. Most of the rest would dismiss it as moralizing. Alan Shepard had never lost his ability to charm women and his old enemy, complacency, would get him into trouble yet again. Once, he dropped his guard and a photographer caught pictures of him in a compromising situation. Glenn got wind of it and managed to convince the newspaper not to run the story. Glenn was furious and called a meeting to let his colleagues know what a near miss they’d had. They interpreted it as interfering in their private lives and it created some hard feelings.

It finally became time to choose who would be first in space. Bob Gilruth called the astronauts to a meeting and asked for a peer vote. Soon afterwards, he announced that Alan Shepard would take the first manned flight with John Glenn as his backup. Shepard was thrilled but could practically hear his colleagues swallowing their disappointment and tried to be a good sport about it.

Alan Shepard in Freedom 7

Preparations for Freedom 7

John Glenn was not one to give up easily. He was still angry over how Alan Shepard had nearly destroyed the reputations of the entire seven by being careless with his philandering. Glenn lobbied NASA officials like Bob Gilruth to change their minds, arguing that it was unfair that the peer vote would be a factor. Gilruth finally told him to quit “back-biting.” Glenn was forced to swallow his pride and support Shepard.

Astronaut Deke Slayton figured out that politics might also be a factor. President Kennedy had just been inaugurated and both he and Shepard had Navy backgrounds. Kennedy spoke glowingly of the future of the space program in his inauguration speech and invited Bill Dana to bring his character, Jose Jimenez, to the inaugural ball.

NASA decided to pretend that the decision on who would make the first flight had been narrowed down to three: Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom and John Glenn. All the astronauts thought it was ridiculous and Shepard made a sarcastic remark when a reporter asked how far in advance he would like to be notified before the flight: “At least before sunrise on launch day.” The press began refering to them as “the first three.”

Meanwhile, the planned fifteen-minute flight would mean months of preparation work. Shepard spent hours in the simulators, rehearsing all the activities they planned to pack into those minutes. Those included looking through a periscope, identifying stars, and testing his ability to manually control the spacecraft in weightlessness. The simulator would also throw technical malfunctions at him. He messed up the very first one and got into an argument with Chris Kraft over it. Kraft had no patience for Shepard’s attitude and pointed out that the mistake he had made could have killed him if it had been a real space flight.

Before Shepard’s flight, they decided to fly a chimpanzee named Ham in a Mercury-Redstone as a test. The flight was a qualified success. Malfunctions caused temperatures to soar and the capsule landed off course. Rocket engineer Wernher von Braun wanted a second test and NASA backed him up. Shepard chafed at the delay and, though the second test was a success, it cost him the chance to be the first man in space. The Soviets launched Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin for a one-orbit space flight. Shepard never did forgive the Soviets for beating him and it sealed his opinion of chimps.

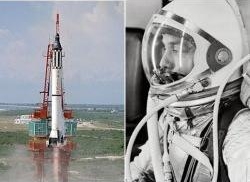

NASA finally unveiled Shepard as the first American to go into space. The reporters asked why it wasn’t Glenn, who had been the favorite to go first, and Powers answered that Shepard “had what all the others had, with just enough to spare to make him the logical man to go first.” It was a pretty vague answer. After one frustrating launch delay, the date was set for May 5, 1961.

Launch Day

Launch days typically started early for the astronauts and both Shepard and Glenn were eating breakfast by 1:30 a.m. Glenn went off to check on the spacecraft, which Shepard had named Freedom 7. The press loved it, believing that the “7” was meant to honor the Mercury Seven. Though the other astronauts would keep the 7 for that reason, Shepard had merely taken it from its official designation of MR-7, the seventh Mercury-Redstone.

NASA physician Bill Douglas checked Shepard over before he got into his spacesuit. Other than a sunburn from too many hours beside the Holiday Inn pool, he was fine. Shepard called Louise and she told him to wave when he launched. “Right, I’ll just open the hatch and stick my arm out,” he joked back.

He suited up and went out to the launchpad with Gus Grissom. They kidded around with a bit of Jose Jimenez routine. His rocket, though small compared to modern ones, seemed impressive in the searchlight. He rode the elevator up seventy feet to the gantry and Glenn helped him squeeze through the small opening. Shepard promptly discovered the joke Glenn had prepared. A sign saying, “No Handball Playing in This Area” and a foldout from a girlie magazine were propped up against the controls. Shepard and Glenn exchanged grins and Glenn retrieved his joke. Technicians bolted the hatch slightly after 6 a.m. and the last face Shepard saw was Glenn’s, grinning through the periscope.

After that, they faced five hours’ worth of delays. Shepard took it in stride at first and his colleagues did their best to keep him relaxed with little jokes. “Don’t cry too much, Jose,” Deke Slayton told him, referring to the Bill Dana routine.

Inevitably: “Man, I gotta go pee.”

“You’re kidding me,” Gordon Cooper radioed back.

“Nope. Check and see if I can get out and relieve myself.”

Cooper checked but the answer was no. Shepard got snappy and told them that if they didn’t let him out, he would go in his suit. The technicians didn’t like that very much, fearing that he would short out the electronics in his suit. They talked the technicians into turning off the electronics. Minutes later, “Well, I’m a wetback now.”

It just seemed like one problem after another. After three hours of waiting, he made his famous snap to technicians: “I’m cooler than you are. Why don’t you fix your little problem and light this candle?”

While technicians sorted out the remaining problems, the launchpad crew piped a recording of Jose Jeminez into the capsule. It caused some consternation in Mission Control as personnel tried to figure out where it was coming from. The countdown clock finally reached zero. “Liftoff and the clock has started,” he radioed to Mission Control. “You’re on your way, Jose,” Deke Slayton answered. Crowds watching live from the beach or listening to the live broadcast went berserk.

Shepard rattled off statistics from his dials until the spacecraft’s vibrations became too much for him to speak clearly. He passed through Max Q, the dangerous point of maximum atmospheric drag in which a rocket was most likely to disintegrate from the pressure, and then reported to Slayton, “OK, it is a lot smoother now.” His capsule successfully separated from the spent rocket and Shepard managed one thing that Gagarin had been unable to do. He took manual control of his spacecraft. He turned Freedom 7 so it was flying blunt end first. Then, he tested his ability to control roll, pitch and yaw, all successfully.

He reached the point of weightlessness four minutes into the flight and discovered that things float in zero G. He tried snatching a loose washer out of the air, but it was out of his reach. Later flights would have a window but they had been unable to work one in for Shepard. He was stuck with looking through the periscope and radioed back, “What a magnificent view.” He would later admit that there wasn’t much to see and he was just trying to make the best of it for the sake of those listening to the live transmission on radio or TV.

Shepard retracted the periscope, fired the retro-rockets to slow down and adjusted Freedom 7‘s attitude for reentry. As he reentered the atmosphere, he met a crushing 11-G load and was again defeated when he tried to talk. He could only keep his muscles tight to maintain conciousness and grunt out the single word, “Okay.” At the proper moment, the parachutes deployed and Freedom 7 touched down 302 miles east of Cape Canaveral. The rescue helicopter quickly reached him and carried him to the USS Lake Champlain, where nearly the entire crew turned out to give him a hero’s reception. When the skipper handed him a tape recorder and asked him to record his thoughts, Shepard couldn’t resist opening with, “My name is Jose Jimenez.”

The doctors who looked him over after the flight reported that he was in good spirits and good shape. He had lost three pounds but was otherwise none the worse for having spent such a long time in Freedom 7 and his only complaint was “the unusual number of needles” used in the post-flight exam.

After The Flight

Kennedy was thrilled that Shepard’s flight was a success. Beyond his genuine interest in space exploration, his presidency had been rocked by the failed Bay of Pigs invasion and other problems and he needed a victory he could show the world. He called Shepard on the Lake Champlain to congratulate him and was soon talking with NASA officials about future plans. Kennedy’s ambitious ideas made some of them nervous. He chose to move forward in the wake of Shepard’s flight and threw down a challenge that would become the ultimate goal of the Space Race. He set the goal of sending men to the moon and returning them to Earth before the decade was out. Some among the President’s advisers must have thought Kennedy was being too ambitious but Congress and the American people loved it.

Shepard was treated like a hero. The parade in New York City rivalled the one they had staged for Charles Lindbergh after his trans-Atlantic flight. Headlines screamed, “Shep did it!” and National Geographic magazine devoted nearly an entire issue to him. Shepard’s flight even had an indirect effect on the stock market as technology companies like IBM soared. Kennedy awarded him with the Distinguished Service Medal. It slipped from his fingers while he was presenting it and he joked, “This medal has gone from the ground up.”

Shepard’s ability to handle the press might have improved, but he wasn’t necessarily prepared for autograph seekers. He could be impatient with people who intruded in his private moments and NASA sent one apology to a man who asked Shepard for his autograph on the beach and got a dressing down instead. If people were lucky enough to catch him in a good mood, though, he might sign an autograph on a napkin.

Gus Grissom had a mostly successful repetition on Shepard’s flight, though his capsule sank and he nearly drowned. Glenn would receive an unexpected reward for his patience when NASA announced that he would take the first orbital flight. His flight in Friendship 7 would be dramatic enough to overshadow Shepard’s flight. Shepard managed to get Glenn back for the “No Handball Playing” sign by planting a stuffed mouse in his spacecraft, another reference to the Jose Jimenez routine.

Shepard was at the Capcom position when an alarming signal came through. The heat shield could have worked its way loose. Shepard thought it was a faulty signal but alerted flight director Chris Kraft anyway. They decided not to tell Glenn but told him to keep his retro-pack clamped on. Glenn made it down safely and told the Mission Control people exactly what he thought of not giving the pilot all the information available. With Glenn’s successful flight, the Americans were beginning to feel like they were back in the Space Race.

The Ice Commander

With his orbital flight, John Glenn came back as the poster boy for NASA. Shepard was still quite well respected among NASA staff, though, and he helped choose the New Nine astronauts. The candidates realized quickly that they were up against Shepard’s “Ice Commander” mode, unforgiving and quick to jump on the slightest flaw: “In July of 1961, you were reported driving an unregistered car. Can you explain this?” Even after they were selected, they met Shepard’s reputation for being a fierce competitor one minute and a friendly drinking buddy the next. Slayton was in line to take the first manned Gemini flight with one of the New Nine, Tom Stafford. However, the chance at a Gemini flight would soon be taken out of his hands by circumstances out of his control. A terrible dizzy spell and persistent ringing in his ears would lead to a diagnosis of Ménière’s disease, which effectively disqualified him for flight.

“I’m sick. Should I just hang it up?” he asked his colleague, Deke Slayton, who had been similarly grounded due to a heart condition and had recently been promoted to chief of flight crew operations. Slayton encouraged him to stick around and offered him a position as head of the Astronaut Office. Shepard wasn’t very enthusiastic about it but accepted anyway. His Ice Commander persona took on new heights as he dressed down his fellow astronauts for the slightest lapse. The fact that he had to watch the newer astronauts take all the flights while he fought off dizzy spells did not help his temper. Some of the new guys tagged him with names like “the Snake,” “the Enforcer,” and sometimes worse. Others, like Gene Cernan, were more forgiving. Cernan stated in his autobiography, “Deke and Al could play the good-cop-bad-cop roles like a couple of New York homicide detectives, Deke instilling confidence and Al demanding more than your very best. The result was a better program.”

He found time for private business ventures and made a tidy profit by investing in banks and hotels. His business ventures weren’t always successful. One bank that he invested in went under and so did a cattle ranch. But for every venture that tanked, several more opportunities would present themselves and he was able to pick and choose. Eventually, word reached the upper ranks of NASA that Shepard was running his businesses on government time. NASA administrator James Webb warned him to watch out for conflicts of interest, though he did offer to allow Shepard some leeway as long as it didn’t interfere with NASA business.

Other astronauts would try to emulate him, with mixed success. One astronaut who washed out of the program would accuse him of hypocritically ripping into his peers who went into business when they were supposed to be astronauts “24 hours a day.” Others would lose money on questionable ventures like wasp breeding. Some astronauts resented Shepard for his success on top of stings heaped on them by the Ice Commander.

He wasn’t entirely icy, though. When Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee died in the Apollo 1 fire, it was one of the few times he cried in public. “I hate those empty-slot flyovers,” he told Deke Slayton, Wally Schirra and public relations officer Paul Haney as they downed scotches after the funeral. NASA would ultimately conclude that they had gotten complacent and had been moving too fast toward the goal of the moon, and Shepard couldn’t disagree.

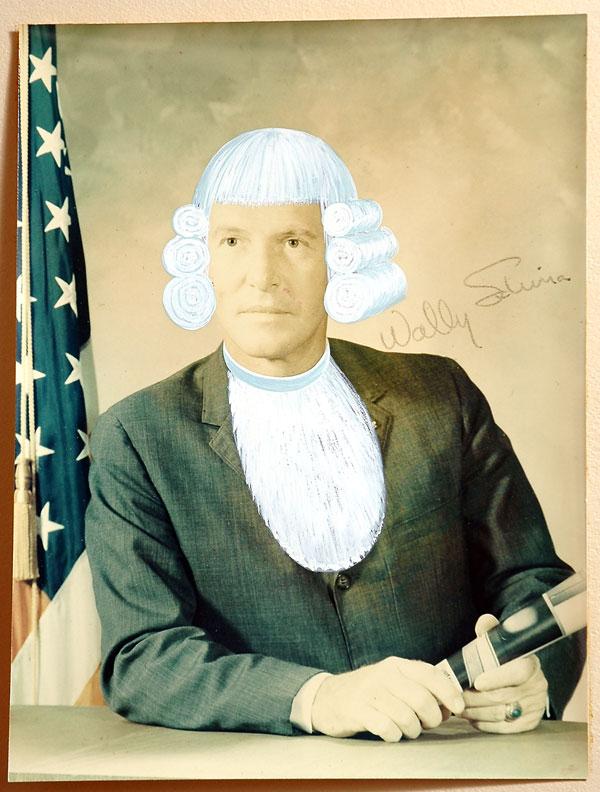

To bolster morale after the fire, NASA decided to honor the sixth anniversary of Alan Shepard’s flight with a fund-raiser for the Ed White Memorial Scholarship Fund. A humorous video produced by Wally Schirra provided some much-needed laughter. Titled Astronaut Hero, or, How To Succeed In Business Without Really Flying Much, it featured planes crashing with the implication that Shepard had been at the controls and narrator Wally Schirra explained that the Navy had begged NASA to take him “in the interest of national security.” Even worse, it featured a segment about Shepard’s dearly hated chimps, Enos and Ham. It even flashed an image of Wally Schirra wearing a white wig, with a claim that he was responsible for Shepard’s success as an astronaut. Shepard got the last laugh. He had found out about the video beforehand and added a bit of his own to the end. He appeared in a humorous rendition of his Ice Commander persona and said, “Wally, I expect to see you in my office at oh-eight-hundred Monday morning.”

To bolster morale after the fire, NASA decided to honor the sixth anniversary of Alan Shepard’s flight with a fund-raiser for the Ed White Memorial Scholarship Fund. A humorous video produced by Wally Schirra provided some much-needed laughter. Titled Astronaut Hero, or, How To Succeed In Business Without Really Flying Much, it featured planes crashing with the implication that Shepard had been at the controls and narrator Wally Schirra explained that the Navy had begged NASA to take him “in the interest of national security.” Even worse, it featured a segment about Shepard’s dearly hated chimps, Enos and Ham. It even flashed an image of Wally Schirra wearing a white wig, with a claim that he was responsible for Shepard’s success as an astronaut. Shepard got the last laugh. He had found out about the video beforehand and added a bit of his own to the end. He appeared in a humorous rendition of his Ice Commander persona and said, “Wally, I expect to see you in my office at oh-eight-hundred Monday morning.”

They would make use of NASA’s T-38 jets to get around, which frequently frustrated Shepard. He was still riding the fame of Freedom 7 and took his turn in the schedule of public appearances he had worked out, referred to as the “week in the barrel.” His Ménière’s disease meant that he couldn’t fly the plane alone, so he rode in the back seat while another astronaut flew. At times like this, his fellows could empathize with the Ice Commander who had once been a top test pilot. His Christian Scientist mother had given him faith in the power of positive thinking and prayer but he wasn’t above keeping an eye open for possible cures. His fellow astronaut, Tom Stafford, was on the lookout as well. One day, he walked into Shepard’s office with some promising news.

A Cure

Stafford told Alan Shepard about Doctor William House in San Francisco, who had an experimental surgery aimed at curing cases like Shepard’s. Dr. House made no promises; in fact, he told Shepard that the surgery could make things worse. Shepard decided it was worth the risk and checked into St. Vincent’s Hospital under a false name. The surgery would hopefully relieve the fluid pressure buildup in his sacculus by inserting a thin tube to drain it. Shepard kept the surgery a secret at first, but had to explain the big bandage on his ear when he arrived home. It would take months to see results. Shepard was so confident that it would work that he wasted no time lobbying for a chance at an Apollo flight. In half a year, the symptoms had completely disappeared. Shepard told Deke Slayton that he was ready for a flight to the moon.

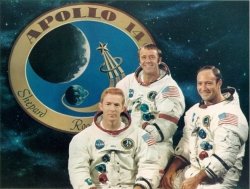

Apollo 14

Many of Shepard’s colleagues were astonished at Shepard’s gall in lobbying for a flight when he wasn’t yet rated to fly jets. As usual, whenever he set his sights on a goal, he did whatever it took to get it. NASA headquarters agreed with some in the ranks that Shepard wasn’t ready for a flight and overrode his selection for Apollo 13.

Many of Shepard’s colleagues were astonished at Shepard’s gall in lobbying for a flight when he wasn’t yet rated to fly jets. As usual, whenever he set his sights on a goal, he did whatever it took to get it. NASA headquarters agreed with some in the ranks that Shepard wasn’t ready for a flight and overrode his selection for Apollo 13.

Training for the Apollo flights was more intense than it had been for Mercury. It meant at least 320 hours in the simulator to master both the command module and lunar module, 240 classroom hours studying subjects like meteorology, physics, rocket propulsion, and computers, and that on top of staying physically fit, enduring sessions in training devices like the centrifuge and the MASTIF, and going on geology field trips. Both Slayton and Shepard were positive he could be ready for Apollo 14 and he was assigned as mission commander. It caused some hard feelings with astronauts who had logged hundreds of hours in space, as compared to Shepard’s one fifteen-minute flight. Gordon Cooper was especially upset, believing that Shepard’s unashamed politicking had cost him a chance at the moon, and told one reporter, “I would rather not speak too much about Captain Shepard. I have my own feelings about him.” Cooper would eventually forgive him.

In the meantime, Shepard watched the Apollo 11 launch, with Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins and the first lunar landing, from the VIP area. While they waited, Shepard’s childhood hero introduced himself: “Captain Shepard? I’m Charles Lindbergh.” The two chatted about the history of aviation and the space program while the last half-hour of the countdown ticked by.

Gene Cernan was assigned as Shepard’s backup and discovered the way to get past that icy barrier. He decided he was going to prove that he could keep up with “the old man.” He congratulated Shepard and promised to support him in every way possible, including replacing him if something should happen. Shepard stared at him for a long, tense moment, and then broke into a grin and offered a handshake. “Geeno, we’re going to have a ball.” Cernan continued to tease Shepard about replacing him until he was injured in a helicopter accident. Finally, he capitulated: “Okay, Al, you win. It’s your flight.”

The “successful failure” of Apollo 13 led to a four-month delay and modifications for Apollo 14, which was not easy on his wife’s nerves. Shepard’s marriage with Louise had remained strong despite his philandering and long absences. Again, she had to deal with reporters who did not respect her privacy and all the tension involved in preparing for a space flight. Louise’s best friend, Dorel, acted as a buffer between her and the rest of the world. Dorel even gave reporters a strong piece of her mind when they scared Louise with a 6 a.m. knock on the door. She kicked them off the property, threatening dire consequences if they ever did that again.

The crew went into quarantine a few weeks before the flight. Shepard could not stand being confined and would routinely “escape” for a few hours. It was like going “over the wall” at West Point, minus having to talk an upperclassman out of giving him a few demerits when he got caught. Once, he and Cernan went out to the launch pad. Cernan recalled it as possibly the only time he had seen Shepard looking humble. Shepard’s commitment had paid off.

Launch of Apollo 14

January 31, 1971

On the days leading up to launch, Shepard was relaxed enough to kid around with reporters when asked what he planned to do on the way to the moon. By then, the politically correct movement had forced Bill Dana to retire Jose Jimenez, but that didn’t stop Shepard from reviving one of the lines: “I plan to cry a lot.” On the launchpad, he was anything but relaxed during a forty-minute delay due to a thunderstorm and returned to his habit of snapping at technicians, “Let’s get on with it!” Finally, the rocket lifted off and reached more than three times the speed that Freedom 7 had. It was much smoother and Shepard felt that the moment weightlessness set in was almost worth the trip by itself.

On the days leading up to launch, Shepard was relaxed enough to kid around with reporters when asked what he planned to do on the way to the moon. By then, the politically correct movement had forced Bill Dana to retire Jose Jimenez, but that didn’t stop Shepard from reviving one of the lines: “I plan to cry a lot.” On the launchpad, he was anything but relaxed during a forty-minute delay due to a thunderstorm and returned to his habit of snapping at technicians, “Let’s get on with it!” Finally, the rocket lifted off and reached more than three times the speed that Freedom 7 had. It was much smoother and Shepard felt that the moment weightlessness set in was almost worth the trip by itself.

The next step was docking with the lunar module, which was stored in a compartment in the third-stage rocket. Shepard and Roosa switched seats so Roosa could handle this part. The command module, called Kitty Hawk, backed toward the lunar module, Antares, with Shepard peering out a side window and advising Roosa. It took a few tries for the docking to take and nobody would have blamed Shepard if he lost his temper. He had fought hard for this flight only to nearly be stopped by a faulty docking mechanism. Finally, he told Roosa to “juice it” and was rewarded with the reassuring sounds of the latches engaging. Engineers still worried about the docking mechanism, which they would again need when Antares docked with Kitty Hawk in lunar orbit.

They continued to coast away from Earth, listening to some Johnny Cash tunes that Roosa had brought on board and taking care of some housekeeping. When it was time to sleep, they snuggled into some sleeping bags and Roosa noticed that Mitchell had brought along a flashlight that he flicked on and off. He was too tired to ask and didn’t consider it important enough to mention to Shepard. The mystery of the flashlight would last throughout the flight.

Landing on the Moon

The trip to the moon was reasonably uneventful. Shepard was somewhat peevish and communicated only essential information with Mission Control. He blamed it on an inability to relax.

They planned to land in a hilly region known as Fra Mauro, which had been the goal of Apollo 13. Scientists believed that it contained some of the oldest rocks in the solar system. Everything seemed normal at first and Antares separated from Kitty Hawk with Shepard and Mitchell on board. A glitch caused Mitchell’s control panel to signal that the abort system had been triggered. Mitchell silenced it, but it flashed again a few seconds later. Shepard barked, “Houston! What’s wrong with this ship?”

Houston realized that it was erroneous programming and sent someone for a computer software engineer who had worked on Antares’ computers at MIT Drapar Labs. The engineer had been sound asleep but he tossed on some clothes and raced to his lab to write a program to fix it. The program was sent up to Mitchell and he used his keyboard to input it. Shepard had hand-picked Mitchell for his brains and did his best not to pester him. They finally reported, “Houston, we got it. We’re commencing with the descent program. … You troops do a nice job down there.”

And then the radar went out. They were supposed to abort if they didn’t have radar but Shepard wasn’t having any of that. On Houston’s advice, he reset the radar’s circuit breaker and told Mitchell that he would have landed anyway.

They successfully landed in Cone Crater. “Not bad for an old man,” joked Capcom Fred Haise.

Alan Shepard exited Antares first. Perhaps he was thinking as much about his years of being grounded and marking time as head of the Astronaut Office as the 250,000-mile trip when he said, “Al is on the surface. And it’s been a long way. But we’re here.” He did his best to describe what he saw and looked at the Earth, which he described as “so incredibly fragile.” He thought of everything he had been through to get to the moon and, for a moment, the emotion was too much for him. He reminded himself that he still had a job to do and went back to work.

Climbing Cone Crater

Alan Shepard and Ed Mitchell worked for five hours, setting up experiments, taking pictures and collecting lunar rocks. Getting around was challenging, partly because it was tough to judge distances on Fra Mauro. It would have been easy to trip on a boulder that had looked miles away.

Alan Shepard and Ed Mitchell worked for five hours, setting up experiments, taking pictures and collecting lunar rocks. Getting around was challenging, partly because it was tough to judge distances on Fra Mauro. It would have been easy to trip on a boulder that had looked miles away.

They finally finished up their first moonwalk and climbed back into the lunar lander. It must have reminded both of them of camping trips. They had landed on an incline, which bugged Mitchell and was starting to get to Shepard.

“Ed? Are you awake?”

“Hell, yes, I’m awake.”

“Do you feel like we’re tipping over?”

“Yeah.”

The lunar lander creaked a bit.

“Ed, did you hear that?”

“Hell, yes, I heard that.”

“What the hell was that?”

“I don’t know.”

Finally, Alan Shepard said, “Ed?”

“What?”

“Why the hell are we whispering?”

They finally decided to give up trying to sleep and told Houston they were ready for their next jaunt. They would try to reach Cone Crater with a two-wheeled cart known as the modularized equipment transporter (MET). Shepard had bet Gene Cernan that he could pull the MET all the way to the top.

Scientists thought Cone Crater had once been a volcano. They had to walk through some hilly terrain to get there. “Okay, we’re really going up a steep slope here,” Shepard radioed to Houston at one point. NASA’s doctors suggested that they leave the MET behind but Shepard didn’t want to lose his bet with Cernan. Each time they topped a ridge, they thought they were getting close but their eyes played tricks on them every time. They were finally forced to quit within 75 feet of Cone Crater. Disappointed, they headed back to the lunar module. But Alan Shepard wasn’t prepared to leave the moon without pulling out his little surprise.

Golf on the Moon

Return to Earth

When the lunar module lifted off from the moon, command module pilot Stu Roosa asked if Shepard had anything profound or prophetic to say. Shepard retorted, “Stu, you know me better than that.” Antares docked with Kitty Hawk and two relieved and exhausted moonwalkers stripped off their EVA suits. Shepard and Roosa were soon asleep and Mitchell would again pull out his flashlight.

Shepard proved to have quite a good appetite during the Apollo 14 mission and was the only astronaut up to that point to actually gain weight in space. After they splashed down and were put in quarantine, he noticed a headline in the New York Times: “Astronaut Gains Weight In Space.” Another unbelievable headline caught his eye: “Astronaut Conducts ESP Experiment on Moon Flight.”

He asked Ed Mitchell, “Did you see this? Isn’t it amazing the things that people make up?”

Mitchell immediately dropped his bombshell: “I did it, boss.”

Shepard stared at him for a few seconds. That explained the flashlight. Mitchell had brought along a small pad with numbers and symbols and, during every sleep cycle, he would pull it out. He had enlisted a few friends to write down the numbers they “heard” at those times. If Shepard had known about it, he would probably have nixed that particular experiment. Now, he could only shrug and go back to his newspaper. Mitchell got the impression that his “boss” was still silently laughing at him.

Once they were sprung from quarantine, the Apollo 14 crew went on the usual round of parades and galas. Nixon invited them to the White House and promoted Roosa and Mitchell. Due to Navy rules, though, Captain Alan Shepard had to wait for his promotion to rear admiral. George H.W. Bush, then acting as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, invited him to serve as a delegate. While sitting in on a meeting of the Security Council, Shepard reflected that it would be a good idea to take the delegates up for a space flight and ask them to point out their countries. The arbitrary man-made boundaries couldn’t be seen from space.

While taking a much-needed vacation with his family, Shepard got a chance to chat with his father. Bart Shepard admitted that he had been wrong to oppose his son’s decision to become an astronaut. The elder Shepard died fifteen months later.

After The Moon

After his return from the moon, Alan Shepard faced the challenging question of what to do next. He did not want to become a politician like John Glenn and he turned down several offers for endorsements. He was content to back out of the public eye and he still had some promising business ventures to follow up on. The Navy was not happy with his decision to retire, dubbing him a “tombstone admiral.”

He sold his shares in successful banks and his Texas oil wells amd opened the first of fifteen successful Kmart stores. When his manager made the mistake of putting Shepard’s face on advertising, Shepard had him reassigned. An attempt to develop lowland property tanked when it was discovered that the area had a bad tendency to flood. He moved among the cream of society with names like Donald Trump, Frank Sinatra and Joan Schnitzer. He also water-skied, drove a Corvette and took up boat racing.

He kept up his love of golf and played in several tournaments. He was not a very good golfer and had to put up with heckling at nearly every course he played on. He never would reveal what brand of ball he had hit on the moon and told one friend when they were gazing up at the moon, “I wonder where my golf ball is.”

As he aged, he began to mellow from his Ice Commander persona. In the aftermath of the book and the movie called The Right Stuff, the remaining Mercury Seven astronauts found themselves back in the public eye and often met at public events. They had drifted apart but found it easy to rekindle their old friendship. Shepard and Glenn still sparred a bit but gradually realized that there was nothing left to compete over. Their old friend Henri Landwirth encouraged them to use their renewed celebrity to raise money for charities and Shepard encouraged Kmart to support Landwirth’s non-profit Give Kids the World. The astronauts and their families also founded the Mercury Seven Foundation, which would later become known as the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation. Landwirth was very supportive and handled much of the initial paperwork. The foundation struggled at first, but Shepard stepped in and helped revive it.

When he heard that fellow astronaut Deke Slayton was dying of brain cancer, Shepard agreed to help him write Moon Shot, which tells the story of the Space Race from the point of view of two Mercury astronauts. Shepard helped promote the book when it was released as a way to help Slayton and his family.

In 1996, Shepard was diagnosed with leukemia. He tried to hide it at first but it showed up in his golf game when he played so badly that one tournament asked him not to come back. Friends could see that he was declining. John Glenn went to doctors at the National Institute of Health for help and, while there was no cure, they were able to suggest tweaks to Shepard’s treatment.

He was able to attend one last event for the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation in 1997. His fellow astronauts pulled out every funny Alan Shepard story they could remember. At the end of the evening, the head of the National Air and Space Museum, Don Engen, took the podium. Engen was a former test pilot and friend of Shepard’s and he had a surprise. He unveiled the Kitty Hawk, which had been on display at the Smithsonian, and announced that he was donating it to the Astronaut Hall of Fame and Museum. Those closest to Shepard remembered that the great Ice Commander revealed how much he had thawed in that moment. He went up to the podium with tears in his eyes and just broke down.

It was the last time many of his friends saw him. He died in his sleep on July 20th, 1998.

Light This Candle: The Life and Times of Alan Shepard

[simple-rss feed=”http://rest.ebay.com/epn/v1/find/item.rss?keyword=Alan+Shepard+astronaut&categoryId1=267&sortOrder=BestMatch&programid=1&campaignid=5337337555&toolid=10039&customid=Alan+Shepard&listingType1=All&lgeo=1&feedType=rss” limit=5]