Ilan Ramon

On the morning of January 16, 2003, Ilan Ramon waited for the countdown to reach zero. Columbia was the first space shuttle to have ever flown and Ramon was Israel’s first astronaut. It was a cold morning but that didn’t stop the usual crowd from gathering to watch this launch. The moment finally arrived and Columbia climbed into orbit for the final time. For sixteen days, Ilan Ramon worked with six American astronauts on science experiments, blissfully unaware of the problems that would doom Columbia along with its crew.

How did an Israeli, or any foreign, astronaut get to fly on the Space Shuttle? In Ramon’s case, that story began before he was even born.

March 1944-

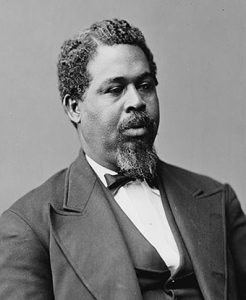

A young teenager by the name of Joachim Joseph had just reached the age when it was time for the bar mitzvah, the Jewish ceremony that marked the passage into adulthood. He was interred in one of the Nazi concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen, where there were no synagogues and Jews were not permitted to perform their traditional rituals. Fortunately, a rabbi named Simon Dasberg had managed to hide a small Torah on his person and keep it with him all those years. He secretly helped Joachim Joseph with his bar mitzvah with cloth hung over the windows so that the Nazi guards couldn’t see what was happening. He gave Joseph the Torah and made him promise to tell his story if he got out. Rabbi Simon Dasberg knew that he probably wouldn’t survive, but Joseph might. Years later, Joachim Joseph met Ilan Ramon and asked him to take the small Torah into space. Ramon was happy to. While Joseph did lose the Torah in the Columbia disaster, he said of it, “I would never have been able to reach the whole world without Ilan. I think the Torah scroll did its job on Earth and in space.

Ramon’s mother was also a Holocaust survivor, having been interred at Auschwitz. Tora and her mother migrated to Israel in 1949, where she met and married Eliezer Wolferman. Eliezer had been born in Germany, but fled Europe in 1935 rather than risk the prosecution of his people becoming worse. He became part of the war to establish Israel as an independent nation. On June 20, 1954, in a small town just outside Tal Aviv, they gave birth to a son, Ilan Wolferman.

Like many top fighter pilots, Ilan Wolferman got his first taste of flying as a teenager. When he turned eighteen and signed up for the mandatory military service, he chose the Israeli Air Force. He got his first taste of combat in the Yom Kippur War, a three-week war between Egypt and Syria. Learning how to fly could be risky and both he and his instructor once had to bail when his steering wheel became stuck. He was injured but was flying again in only a few months. After his graduation in 1974, he changed his name to Ilan Ramon so that he could have a more Hebrew-sounding name.

A few years later, the American F-16 went into production. This was a light, fast new jet fighter that many American allies, including Israel, wanted for their own air force. Ramon was one of several pilots selected to train in the F-16 at Hill Air Force Base in Utah. When he returned, he was assigned to be the deputy squadron commander-B for an F-16 squadron. Other F-16 pilots were impressed by the talented young man and received compliments from people like Major General Amos Yadlin, who commented that he was “not like most macho top-gun fliers.” He knew how to keep a cool head.

His superior officers were impressed enough to select him for a 1981 mission to destroy an Iraqi nuclear reactor. By flying close together, they could fool radar into thinking that they were an ordinary passenger jetliner. He also fought in Operation Peace for Galilee, in which Israel invaded southern Lebanon to drive out terrorists who had been firing rockets at Israel.

In 1983, Ramon temporarily left flying to study electronics and computer engineering at Tel Aviv University. He did not completely abandon aviation, however, and found a job at Israel Aircraft Industries, which was developing new fighter jets. He returned to the Israeli Air Force in 1988 because he enjoyed the challenge and he liked working with the devoted, highly educated and friendly people he worked with in the air force. He served as a deputy squadron commander for the F-16 Phantom Squadron and then was promoted to squadron commander in 1990. In 1992, he was reassigned to become Head of the Aircraft Branch of the Operations Requirement Department. He received a promotion to colonel in 1994 and was assigned to take charge of the IAF’s department of weapons development. It meant making decisions about developing and purchasing airplanes and their weapons systems, along with ground-based equipment such as computers and radar. He held that position until April 1997, when he received an important phone call.

About the same time he was settling into his role as chief of weapons development, American president Bill Clinton and Israeli prime minister Shimon Peres were discussing the possibility of having an Israeli astronaut fly on the Space Shuttle. Ramon had all the right credentials. He was a member of the air force, he had a degree in electronics and computer engineering, and he had experience with scientific work. The competition was fierce, but Ilan Ramon prevailed.

At first, he was sure that somebody was playing a joke on him. Soon, his entire family moved from Israel to Houston, Texas. It was definitely different. His children had to learn English and get into a public school in Houston, and they found a local synagogue.

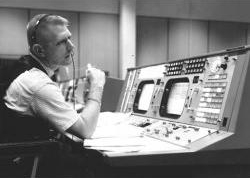

It takes years of training to become an astronaut and he jumped right into it at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC). He studied shuttle systems, navigation, astronomy, physics and survival training. When he was ready, he was assigned as part of the STS-107 crew, which would lift off in the Columbia. That meant more training as he learned how to operate the experiments that would be flown on that mission and coordinate activities with his crewmates to insure that everything ran smoothly.

Israel watched him closely. 2002 was declared “The Year of Space” and he was featured on an Israeli postage stamp. Children followed his training carefully. Aware of the importance of his mission to his home country, he began planning what to take with him. Each astronaut was allowed to take small personal mementos on their flight. He had the Torah that Joachim Joseph had given him. He also had a sketch called Moon Landscape, an imaginary drawing of the Earth seen from the Moon made by a 14-year-old boy who had not survived the Holocaust, and a mezuzah, a small piece of parchment showing a passage from the Torah that had been rolled up and placed in a decorative container. He requested that NASA prepare some kosher food for his meals on the Columbia.

There had been some reservations about having the Israeli equivalent of a Top Gun fighter pilot handling scientific packages, but Ilan Ramon quickly settled them. The personnel on the crew training team remembered that he picked up procedures very quickly and with very few questions. He earned the nickname of “The Machine” because of his ability to glance at a procedure list once and perform it perfectly.

In the weeks before the launch, the crew went into isolation at Cape Canaveral. Anybody wanting to see them had to be cleared to help insure that the crew wouldn’t be infected with any easily communicable disease. Contact with the outside world was mostly limited to immediate family and any NASA employees whose duties made it necessary for them to see the crew directly.

Security was also tightened. While nobody expected trouble, NASA did not want anything to happen to Israel’s first astronaut or his family. Even simple things like the Ramon family having breakfast at a local restaurant meant sending police out to inspect the restaurant, stopping traffic along the route, and ushering the family into a separate part of the restaurant. Service was fast. Drawing on his security training, Ramon suggested that each family lodge in a separate location, but STS-107 Shuttle commander Rick Husband decided to do it the usual way and the families stayed at a local hotel.

Finally, the Columbia was ready to fly. Ramon’s entire family was proud of him. “I know he is laughing all the way up,” his wife Rona told reporters. His son Assaf commented, “I wanted to be a fighter pilot. Now I want to go to space like my dad.”

Israel watched the launch through a live TV special. People in popular restaurants were heard counting down along with the television. On January 16, 2003, the daily news, usually so full of violence, began with, “Finally we can begin with some good news.” Israel now had reason to laugh right along with Ramon.

While in orbit, Ilan Ramon talked about the view of Earth and especially flying over Israel. He wore a patch of the Israeli flag on both his spacesuit and his astronaut’s uniform and thought of Israeli’s history of border skirmishes and wars. “When we go up into space, Earth is one unity and no borders are seen from there. That’s the vision that NASA carries on and that is my vision too.” He wasn’t the first astronaut to express such sentiments and he wouldn’t be the last.

Columbia carried a total of eighty experiments from a wide variety of scientific fields. Ramon’s experiments included the Mediterranean Israeli Dust Experiment (MEIDEX), in which he photographed dust clouds in the Mediterranean region. Scientists hoped that this would provide data about Earth’s atmosphere, climate, weather and the movement of viruses. His friend Joachim Joseph was one of several scientists working on the experiment. Ramon kept Joseph informed about the progress of the experiment with a series of data downloads.

He also worked on an experiment that studied how flames create soot. Normally, fire is undesirable on any spacecraft, but scientists had found ways to create fire more safely in small containers. He used these containers to burn various materials to study the reasons that some soot is dirtier than others. Medical experiments included a study of bone cell grown in space and a study of his own heartbeat and bodily functions while he slept.

Ramon was especially interested in a program called Space Technology and Research Students (STARS), in which students could submit experiment ideas for a chance for them to fly on the Space Shuttle. His student experiments included studies of how spiders spun webs in space, containers of silkworms and bees to study their reactions to space, and some fish eggs to study how quickly they would develop in a space environment. Students also learned about how a scientific experiment could produce surprising results. One of the silkworms became a butterfly. Ants that were expected to create tunnels more slowly in space “ended up tunneling like maniacs” according to one American student. An Israeli student experiment studied the growth of crystals in space. Instead of growing in a straight line as expected, the crystals grew in multiple directions that Ramon described as looking like crystal roots. Because their experiments had flown and Ramon had taken the time to speak with students about their experiments, they felt closely connected to the space program. After the loss of Columbia, some students decided to continue their research in honor of the fallen astronauts.

When February 1st, 2003, dawned, the astronauts were making preparations for return to Earth. Cameras on the launchpad had shown that some debris had fallen from the shuttle during launch and possibly damaged it, but no one thought it was a serious concern. They turned out to be mistaken. When the Columbia broke apart somewhere over Texas, Ilan Ramon died along with the rest of the crew. Miraculously, his in-flight diary was one of the few items that survived intact and was still legible. While both America and Israel mourned, his body was returned to his home country. Lod Air Force Base in Israel hosted his funeral on February 11, 2003.

His oldest son, Asaf Ramon, joined the Israeli Air Force and died in an F-16 crash during flight training in September 2009. The rest of his family still lives in Israel.