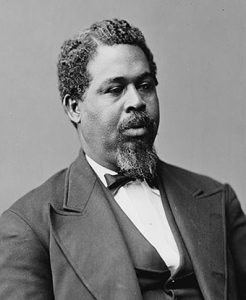

David Brown

David Brown didn’t always dream of becoming an astronaut. Growing up, he thought going into space was for larger-than-life people like John Glenn or Neil Armstrong. “I thought they were movie stars,” he said of it, and he just figured that becoming one of them was out of reach for a normal kid like him. Born in 1956, he didn’t remember much about the Mercury Project, but he remembered watching footage of the Gemini and Apollo programs.

Without knowing it at the time, he quickly set out on a path that would bring him to the world of NASA. He remembered taking his first airplane ride when he was just seven years old. A friend took him up in a small private airplane and David Brown watched the front wheel because he wanted to remember the moment they became airborne.

He graduated from Yorktown High School in Arlington, Virginia, and went on to the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg. While there, he joined the gymnastics team and met a coach who believed that both athletics and education should be a long-term investment. The coach taught Brown a lot about teamwork. To help pay the bills while at college, Brown became an acrobat, 7-foot unicyclist and stilt walker for Circus Kingdom.

After his graduation from William and Mary, Brown earned an M.D. at Eastern Virginia Medical School, receiving his diploma in 1982. He joined the Navy in 1984 and became a flight surgeon. While working with naval aviators, he realized that pilots and medical personnel didn’t always speak the same language. Pilots also traditionally disliked flight surgeons who could ground them for seemingly minor reasons. When he heard about a program for flight surgeons who wanted to become aviators, he decided to apply in the hope that he could form a bridge between surgeons and pilots.

He was rejected the first time but made it into flight training on his second try. In 1988, he became one of the few flight surgeons who were also aviators. He found that it helped to have a way to relate to pilots and, in the STS-107 pre-flight interview, he referred to the idea that he was acting as a translator.

In 1996, he heard that NASA was looking for astronauts and he decided to apply, figuring that the astronaut corp might have room for a flight surgeon who was also a pilot. As part of his training, he became qualified in the T-38. He became known as “Doc” in the astronaut community.

While working at the Johnson Space Center and with other astronauts out in the field, he became known as something of a shutterbug and amateur video cameraman. “Just act like a little brown squirrel,” he would say whenever he had a camera in his hand. Some astronauts were more tolerant of his filming activities than others and the families of his STS-107 crewmates remembered that they sometimes got annoyed with him. A lot of his footage made it into the Discovery Channel’s Columbia Diaries after the disaster.

He was also known for his humor-tinged humility. Once, when he had some questions after a simulator run, he asked a flight engineer, “May I borrow your brain?” The idea that people actually sought out his autograph seemed to amuse him and he occasionally searched eBay to see what it was going for. He never expected too much and once cheerfully reported to STS-107 crewmate Kalpana Chawla that one autographed picture sold for eight dollars.

Occasionally, his competitive side came out and he caused some confusion by stating that he was going to be the primary flight engineer, a role that had gone to Kalpana Chawla, during a press conference. Fellow crewmate Mike Anderson was quickly able to clear up the misunderstanding. His competitive side was an attitude that he continuously worked to keep under control. If he ever thought about the risks involved in being an astronaut, he might have just thought that NASA’s work in various scientific fields was worth it.”Whatever I can do to contribute to science, to improve science, I think is really great,” he told interviewers before the STS-107 flight.

STS-107 was his first crew assignment. When John Glenn had been there for STS-95, David Brown remembered him saying, “You know, when you get up there, you need to make sure you look out the window.” Brown thought that was among the best advice he had received. The view from orbit was magnificent and many astronauts, especially those who came from troubled parts of the world, were heard to comment that nobody ever saw any national boundaries when they were in space. In an email from space, Brown commented that watching Earth through the window was like watching a big Imax movie.

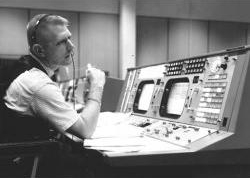

Of course, he didn’t spend most of his time Earth-gazing. The Columbia had more than 80 experiments on board. To keep up with them all, the crew had split into the Red Shift and Blue Shift so that they could work around the clock. On the Blue Shift, Brown assisted with or monitored experiments that included FREESTAR, a collection of experiments that included the Mediterranean Israeli Dust Experiment designed to monitor the behavior of atmospheric dust in the Mediterranean region, and the Solar Constant Experiment-3, designed to monitor the behavior of the solar constant during a solar cycle. Results of these experiments were periodically sent back to Earth. As one of two physicians on board, he also worked with experiments that studied osteoporosis, the behavior of viruses in space, protein turnover in a space environment, and a study of renal stone formation. He compared the work, and especially training for everything, to running a marathon as opposed to sprinting.

When he talked about what he thought the legacy of STS-107 was going to be, he talked about the scientific work. It was really an international effort, with experiments from across the U.S., Canada, Europe and Israel. He said in one of his last emails to friends and family to Earth:

“The science has been great and we accomplished a lot. I could write more about it but that would take hours. My crewmates are like my family. It will be hard to leave them after 2½ years.”

When David Brown died during STS-107’s entry on February 1, 2003, his brother remembered his expectations that the program would continue. It took a few years before the Space Shuttle flew again and there were many who believed that the loss of Columbia and her crew was the beginning of the end for the Space Shuttle program. Friends and family remembered him as a funny and talented astronaut.

David Brown had requested “Silver Inches” by Enya as a wake-up tune and it was selected for him on the last day of their flight.

[ebayfeedsforwordpress feed=”http://rest.ebay.com/epn/v1/find/item.rss?keyword=%28space+shuttle%2Cnasa+astronauts%2Cspace+shuttle+astronauts%2Castronaut+david+brown%29&sortOrder=BestMatch&programid=1&campaignid=5337337555&toolid=10039&listingType1=All&lgeo=1&feedType=rss” items=”10″]