William McCool

Long before William McCool became a Space Shuttle astronaut, he had earned a reputation for being competitive. Attending high school in the 1970s, he was part of the track team and liked running so much that he often ran to the local library to study. At least one classmate recalled that McCool wasn’t very good at basketball, but wouldn’t quit until he could beat his opponent. He could also take a joke. When he admitted to a teacher that he didn’t know what logarithms were, the teacher exclaimed, “Oh, no! This man is from a foreign country.” Once the laughing died down, the teacher took a time-out to explain logarithms and remembered that McCool seemed to grasp it almost immediately. He was smart and studied a lot, even when kids around him were having fun, but he somehow managed to not give the impression that he was a geek.

After graduating from Coronado High School, he applied for both the Air Force and Naval Academies in 1979 with one eye on the running teams of both. He was accepted into both and joined Annapolis, where Al Cantello was the coach of the track team. Cantello had thrown javelin for the 1960 U.S. Olympic team before joining the staff of the Naval Acadamy as a coach.

During his plebe year at the Naval Academy, Cantello asked McCool how much of his life he thought would be devoted to the team. McCool considered his priorities at the Academy, which included academics and adapting to the disciplined life of the Navy, and answered, “Twenty percent.” Cantello said, “You will never be a runner here.” McCool’s commitment, charisma and eagerness to improve made him popular with the team even when they made him sing songs on the team bus. By his fourth year at the Academy, he revised his answer up to “Ninety percent”, was voted team captain and developed a formidable time in the 10,000-meter race.

He developed successful strategies for each track meet and people naturally gravitated towards him. He rallied support for the annual Army-Navy track meet and could be heard in the halls shouting, “Four-and-a-half days ’til Army, will you be there?” He would have graduated first in his class if he hadn’t been caught running with his shirt off and received a few demerits.

During his time in the Navy, he earned a Master’s degree in Computer Science from the University of Maryland and another Master’s in aeronautical engineering at the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School. He completed flight training in 1986 and was assigned to Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 129 at Whidbey Island, Washington, where he learned how to fly EA-6B Prowlers. The Prowler wasn’t considered a “hot” jet plane that Top Gun cadets would have pounced on, but it suited McCool. He also attended the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School and graduated first in his class. He was assigned to work on improvements to the EA6B Prowler, which had an advanced electronics system, at Patuxent River Air Force Base. Another of his projects was the TA-4J Skyhawk, which had been produced since 1969 and was continually being improved until it was replaced by the T-45A Goshawk. When his tour at Pax River was over, he was transferred to Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 132 on the Aircraft Carrier U.S.S. Enterprise.

When his family encouraged him to apply as an astronaut, he was hesitant at first. He didn’t want to move his wife and kids to Houston. Finally, he agreed to give it a try. He was rejected the first time, but his competitive nature took over and he applied again. He was finally accepted in April 1996. Any lingering doubts were settled when his squadron commander threatened to kick him out if he didn’t accept.

While training as an astronaut, his computer skills came in handy when he was assigned to develop an interface for a new computer software program for the Space Shuttle. He also worked with the international partners to troubleshoot components being developed for the International Space Station.

He finally received a crew assignment to STS-107, but the mission was scrubbed because that particular Shuttle was needed for a repair on the Hubble Space Telescope and scrubbed again because the Columbia was not designed for missions to the International Space Station. He was beginning to get irritated. So many scrubs were not what he had signed up for.

In the meantime, training was enough to keep him occupied. NASA had heard from another astronaut about a program called the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) in Wyoming. Shuttle Commander Rick Husband liked the idea of using NOLS as a team-building program. The crew flew out and met Instructor Andrew Cline and Director John Kanengieter. The two NOLS employees hadn’t been too sure about working with the group, especially when they heard that William McCool was a fighter pilot who could have come off as a hotshot. However, they hit it off and the instructors were impressed by how friendly the entire group was. They set off to spend the next ten days hiking in the wilderness.

On the seventh day of their trip, McCool had the idea of challenging Cline and Kanengieter to a competition. The astronauts would have a head start and then the two instructors would try to catch up and spot them without being seen. Andrew Cline remembered later that he didn’t think it would be much of a challenge. They knew the layout of the land pretty well and went off the path to try sneaking up on the crew. They overlooked the fact that most of the astronauts had military experience and were busy laying out an ambush. The NOLS teachers had to go through a ridge and the crew hid behind rocks and downed branches. When the two teachers were spotted in the ridge, the crew charged, whooping and hollering.

The STS-107 crew took turns cooking. On the ninth night, McCool went fishing with Ilan Ramon and Rick Husband and made a variation of fish chowder. McCool also got into a multi-day cribbage tournament with the two instructors. He kept losing, but he also kept coming back for more because he was convinced he could win. Finally, on the last night, he actually managed to win a game. John Kanengieter later admitted that he let McCool win.

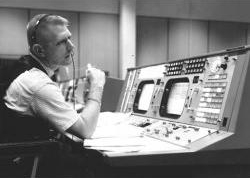

Finally, the crew had a mission that was suitable for the Columbia and they launched on January 16, 2003. During launch, a small piece of foam broke off the rocket and damaged Columbia‘s wing, breaking off some tiles in a critical location. Although controllers had incomplete information, they decided that it wasn’t likely to be a problem; after all, astronauts like Kalpana Chawla had commented that Columbia looked like somebody had been shooting at it after landing and it had never failed to return.

For sixteen days, McCool acted as pilot and assisted with experiments. The crew frequently (and fortunately) sent most of their results to various investigators assigned to the experiments. On February 1, 2003, the entire crew lost their lives when Columbia broke apart sixteen minutes before landing.

[ebayfeedsforwordpress feed=”http://rest.ebay.com/epn/v1/find/item.rss?keyword=%28astronaut+william+mccool%2CSTS-107+Columbia%29&sortOrder=BestMatch&programid=1&campaignid=5337337555&toolid=10039&listingType1=All&feedType=rss&lgeo=1″ items=”15″]