Planet Mars

Named after the Roman god of war, Mars is also often referred to as the “Red Planet.” It is a favorite among science fiction writers and stargazers. As an interesting note, Mars was the Roman god of agriculture before becoming associated with the Greek god Ares. Those in favor of terraforming and colonizing Mars may prefer this association.

Manned Mission to Mars

Mars by the Numbers

- Average distance from sun: 1.5237 AU (2.279 X 10^8 km) About one and a half times Earth’s distance from the sun.

- Orbital Period (Martian year): 1.88 years (686.95 days)

- Period of rotation (Martian day): 24 hours, 37 minutes, 22.6 seconds

- Diameter at equator: 6792 km (53% Earth’s diameter)

- Mass: 6.424 X 10^23 kg (10.75% Earth’s mass)

- Surface gravity: 0.379 G (37.9% Earth’s gravity)

- Escape velocity: 5.0 km/s (45% the escape velocity of Earth)

- Surface temperature: -140 to 20 degrees Celsius (-220 to 68 degrees Farenheit)

Observing Mars

Ground-based observatories have studied Mars extensively, but it is a difficult target for even the largest telescopes because of its distance and size. Like all planets, it appears to move in relation to the stars in the sky over the course of a year. (If an object appears to move very fast against the stars, it is probably a satellite or airplane.) It has a reddish glow and appears to twinkle because the light has to pass through Earth’s atmosphere before you can see it.

Landmarks on Mars

Contrary to science fiction tales, Mars has no artificial canals. The canals of Mars are an optical illusion that originated with Percival Lawrence Lowell, who built the Lowell Observatory in Arizona. He spent 14 years observing Mars and considered the canals a sign of intelligent life. Later studies showed that the canals were simply a product of an optical trick. The human eye will naturally look for patterns and the “canal system” was simply an illusory interpretation of natural features on Mars.

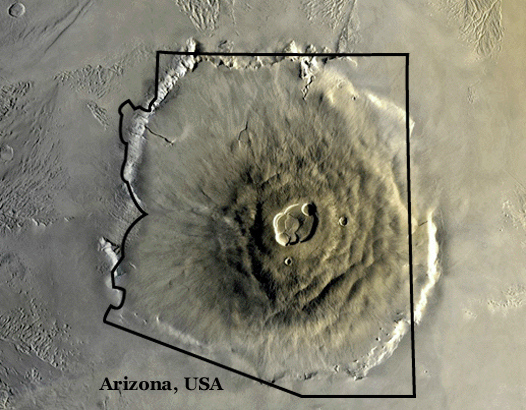

Interesting (and real) landmarks on Mars include Olympus Mons, the tallest volcano and mountain in the solar system. It is 27 kilometers, or 16.7 miles, tall. Olympus Mons is a shield volcano, meaning that plate tectonics don’t force it to move. It is actually wider than it is tall and, when it was active, it forced lava up through the same crust it always has. However, it is estimated that it has been inactive for about two million years.

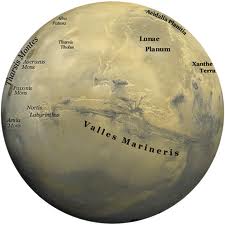

Mars is also home to the deepest crevice in the Solar System, named Valles Marineris. If you imagine the Grand Canyon, only wider, longer, and deeper, you won’t be far wrong. Valles Marineris is 4,000 km long, 200 km wide, and up to 7 km deep. If it was on Earth, it could easily stretch from San Francisco to New York.

Early Mars Exploration

For a long time, we were unable to send rockets and space probes to the moon and other places in the solar system. We could only observe the sky with our own eyes and with telescopes. As a result, early astronomers assumed that the Sun, stars, and planets revolved around Earth. Copernicus was the first to prove that Earth and the planets revolved around the sun and Kepler refined this model using data given to him by his mentor, Brahe. Brahe initially gave Kepler the data for Mars, expecting him to solve its orbit, and Kepler used this data to prove that planets have elliptical (oval-shaped) orbits.

In 1659, Christiaan Huygans became the first to describe a feature on Mars believed to be Syrtis Major. He made a sketch of it and declared that it appeared to be a bog. Of course, we now know that there are no bogs on Mars because there is not enough liquid water. Huygans also made the first estimate of Mars’ size, believing it to be about 60% the size of Earth, and he also estimated a Martian day to be about 24 hours. He also published a book on whether there is life on Mars, titled Cosmotheoros.

Gian Cassini and Jean Richer measured the distance to Mars in 1672. Jean Richer went to Cayenne, French Guiana in South America so he could measure Mars’ position in the sky. Gian Cassini did the same thing in Paris, France. By comparing the results, they were able to determine the distance to Mars at the time of their measurements. The result of the calculation helped determine the size of the Astronomical Unit.

William Herschel was the first to identify the polar caps as such in 1781. They had been previously observed by Maraldi, Huygans, and Gian Cassini, but none of them ever suggested that they were polar caps. Herschel also discovered that the inclination of Mars axis of rotation is approximately 24 degrees. He also suggested in an address to the Royal Society that Mars had a considerable atmosphere and, perhaps, life similar to Earth’s.

Giovanni Schiaparelli produced the first detailed map of Mars in 1877 and gave names to many of the features he observed with his 8.5-inch refractor. Many of those names became widely accepted. The map included naturally occurring channels that Schiaparelli called canali.

Also during 1877, Asaph Hall discovered the moons of Mars and named them Deimos and Phobos, after the sons of Ares, God of War.

In 1894, the Lowell Observatory was founded for the purpose of observing Mars. It initially included a 12-inch refractor and an 18-inch refractor. Observations of Mars took place continuously from the end of May 1894 through April 1895 by Lowell and his assistants.

In 1905, Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius postulated that the observed changes in Mars’ features, previously thought to be caused by seasonal changes in Martian vegetation, was actually due to chemical reactions caused by melting water from the Martian polar caps.

Mars Probes

The USSR and USA began sending probes to Mars in the 1960s. The USSR’s early attempts ended in failure and the USA was the first to send a probe to Mars, Mariner 4, which sent back 22 photos as it flew by in July, 1965. These pictures revealed a vast, barren wilderness. Mariners 6 and 7 also successfully reached Mars in 1969, sending back hundreds of photos.

Mariner 9 was the first to take close-up photograph of Deimos and Phobos in November 1971. It also took thousands of photographs of Martian features, including volcanoes, canyons and ancient riverbeds.

The Soviet Union finally reached Mars in 1971 with Mars 2 and Mars 3. Mars 2 crashed, but Mars 3 was the first to make a landing on the surface of Mars. Unfortunately, Mars 3 stopped communicating soon afterward.

The U.S. probes Viking 1 and 2 successfully landed on Mars during the summer of 1976. Bio-tests of the soil yielded interesting data, but it was inconclusive whether Mars actually had life.

Phobos 1 and 2 were sent by the Soviet Union in 1988. Phobos 1 was lost due to a software glitch. Phobos 2 reached Mars but a computer malfunction ended its mission.

After an 18-year haitus, the U.S. sent Mars Observer in 1993, but its transmission was lost 3 days before it was to go into orbit around Mars. Mars Global Surveyor succeeded in 1996, however, and sent back 120,000 pictures and data suggesting that there might be water under the Martian surface.

The next year, Pathfinder reached Mars and sent out its probe, Surveyor. Data sent back suggested that Mars had once been warm and had liquid water in a past era.

Japan joined in with a probe initially called Planet-B and later renamed Nozomi, which is Japanese for “Hope.” Its mission was to search for water on Mars and measure its magnetic field. Unfortunately, it suffered a series of malfunctions and finally settled into orbit around the sun.

In 2004, the U.S. probes Spirit and Opportunity landed on Mars. These probes proved quite durable, working for more than 1,000 days, although at one point Spirit could only travel in reverse due to a wheel malfunction. It meant extreme caution for the remote-control operators to make certain it didn’t get stuck anywhere. They discovered evidence of liquid water and a more substantial atmosphere in the Martian past.

The Mars Rover “Curiosity” reached Mars and landed on August 6, 2012. It was one of the trickiest landings ever attempted by NASA and became widely known as the “Seven Minutes of Terror”. It contains some of the most advanced scientific instruments sent into space for the purpose of studying the geology and possibility of life on Mars and demonstrates the capability of sending heavier robots and technology to Mars.

On September 24, 2014, India’s Mangalyaan orbiter, also known as the Mars Orbital Mission (MOM), went into Mars orbit. It cost only $74,000,000 and is expected to search the Martian atmosphere for signs of life.

Is Mars Habitable?

That’s a very good question. Martian probes have repeatedly found evidence of past water activity and present deposits of frozen water on Mars. Dr. Laurie Leshin discusses the possibility that Mars is presently habitable if one doesn’t mind a little risk and a lot of hard work.

The Future of Mars Exploration

or, “Why Should NASA Have All The Fun?”

NASA’s future plans include a manned expedition to Mars by the year 2030, assuming that they receive adequate funding from Congress. For this purpose, they are developing the Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle with an intention of making the first test launch by 2017.

Dennis Tito Discusses “Inspiration Mars”

Private organizations and individuals also intend to send people to Mars. Dennis Tito, best known for being the first space tourist to visit the International Space Station, has announced plans to send two people on a 501-day Martian flyby with potential target dates of 2018 and 2021.

Mars One Introduction

Organizations include the non-profit Mars One, which plans to set up a permanent settlement on Mars. They will be selecting the first candidates later this year and plan on sending the first settlers by 2027. Because funding is a constant obstacle in any space exploration, Mars Ones plans to raise money and educate people about training its astronauts with a multi-year media blitz that will provide an up-close look at the lives of their astronauts. Founder Bas Lansdorp is currently in the process of lining up investors to help provide funding.

The Future of Planetary Exploration

Professor Stephen Squyres has participated in several robotic exploration missions including the Mars Exploration Rovers. Here, he discusses planning for the future of interplanetary exploration.