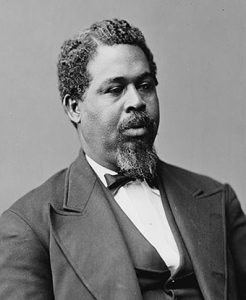

Henri Landwirth

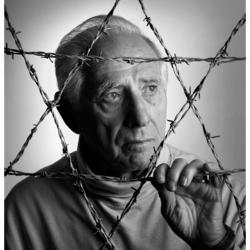

Henri Landwirth is a Holocaust survivor who came to America looking for a fresh start. He went into the hotel business and worked his way up to become part owner of a few successful Disney World-area Holiday Inns, and then left it all to found non-profits like Give Kids The World, Dignity U Wear and Hate Hurts. Henri Landwirth is most famous for his indirect involvement in the Space Race, during which he managed the Starlite Hotel and a Holiday Inn in Cocoa Beach.

Henri Landwirth Documentary

Youth in Poland

For the first thirteen years of Henri Landwirth’s life, he lived in Poland with a normal Jewish family. His parents were named Max and Fanny, and he had a twin sister named Margot, whom he described as the real fighter of the family. His father’s job as a salesman took him away from home a lot and his mother was the real disciplinarian of the family. He had no doubt that they loved him and his sister.

His father wanted to flee Poland when he noticed an alarming upswing of anti-Jewish sentiment but his mother held firm. They were staying. It proved to be pivotal. Germans invaded the Landwirth home and took all their valuables. A young Henri Landwirth saw the whole thing and thought his father was going to die. But he didn’t that day. Not long afterwards, the Germans arrested his father without cause or charges. Despite efforts by Fanny Landwirth to free him, he was shot in the back of the head and buried in an unmarked grave.

As the Germans gained power, they herded all the Jews in Krakow into a walled-off ghetto, including the remaining Landwirth family. It was filthy and overcrowded, and there was less to eat. This was only the first step in Hitler’s plan to exterminate Jews and other people he deemed undesirable. Although anyone caught taking part in Jewish ceremonies would be killed, Henri Landwirth’s family insisted that a bar mitzvah be held for him. Two men guarded the door during the ceremony.

Despite the harsh conditions in the ghetto, Landwirth saw many acts of kindness and courage from other prisoners. Food was shared whenever possible and they did their best to encourage each other. When one infant’s mother died, word spread quickly and someone was found to nurse her. Another woman challenged the Nazis, “You cannot treat human beings this way!” She was shot and the guard stepped over her like she was nothing. Perhaps none of them dreamed that things could be even worse. But Nazis would round up prisoners for deportation to work and death camps on a regular basis and, inevitably, Henri Landwirth was one of those chosen.

The Concentration Camps

Hunger was a constant companion for prisoners in the camps. Rations were a tiny piece of bread doled out daily and, if they were lucky, a small bowl of thin and rancid soup. This starvation diet reduced people like Henri Landwirth to the instinctive level. Every day was a battle to survive. He remembers one day when they were forced to stand in line naked. The man in front of him looked like a skeleton with skin still clinging to him. Landwirth realized that the man behind him was seeing the same thing.

The train ride to the first concentration camp, called Ostrowitz, was horrendous. They were packed in like cattle with no place to lay down or any bathroom facilities. He doesn’t recall the exact date they left the ghetto, but it was probably mid-winter and certainly frigid. The prisoners were segregated by gender and the ride lasted for days without food or water.

Months after they reached Ostrowitz, Landwirth found out that his mother was living on the other side of the camp and, risking his life, sneaked over to see her. It was painful for him to see her in a starved state. She asked him, “You wouldn’t have an extra piece of bread, son, would you?” Of course, he didn’t. It was the last time he spoke to his mother.

He was found by a fellow inmate named Maurice Bauman. Bauman had been asked by a cousin to look after him and reluctantly told him that his father had been shot by Nazis. They stuck together and, when Bauman was forced to stand between two electric fences with enough current to kill a man, Landwirth and Bauman’s brother kept him alive by keeping him awake.

The Nazis moved Landwirth and several other inmates to another camp called Auschwitz. It was there that he saw his mother for the last time, from a distance. He considered calling to her, but could not bring himself to risk her life. After that, only the hope that his mother and sister were still alive, and a growing hatred for the Nazis, kept him going.

Another train took him on to Matthausen. Each prisoner was given a single piece of bread. Landwirth tried to save his, but somebody stole it. When they arrived, each prisoner was forced to strip and stand outside in freezing weather. Many of them died. Landwirth lost track of his friend, Maurice Bauman.

He went on to a large weapons plant he didn’t know the name of and was given the job of helping put together anti-aircraft guns. An organized prisoners’ resistance contacted him and told him he could help sabotage the weapons. All he had to do was take inaccurate measurements and the weapon would blow up in the Nazis’ faces. Getting caught meant being hung but that didn’t seem like so much of a risk by this point. Landwirth was happy to help and, in exchange, the Resistance told him that they would help him when he got sick. And he did get sick, with typhus, after eating some diseased food. The other prisoners smuggled medicine to him. He recovered but was beginning to feel the effects of a nervous breakdown.

Escape

Germany was losing the war by this point and the Nazis decided to march all the prisoners toward the interior of Germany, away from the front lines. Landwirth kept trying to encourage the other prisoners to make a run for it. The Nazis would not be able to catch them all if they tried to escape now. A guard heard him and cracked him over the head with a rifle. It cracked his skull and he fell unconscious. The guard left him for dead and it saved his life. Most of the remaining prisoners were killed.

Somehow, he regained consciousness. His head hurt, his legs were wounded, and his split skull probably contributed to the nervous breakdown. He was soon recaptured and taken to a jail. When they came for him three days later, he was numb, half mad and no longer feared the Nazis. The soldier made him beg for mercy. Landwirth knew that he meant to kill him but did so anyway. It was like he was watching himself. The soldier must have seen his dazed expression and told him to run. He did and was recaptured by a different band of soldiers. Their leader ordered some men to take him and two other prisoners out to the woods and shoot them. The soldiers took them out to the woods and said to each other, “I don’t want to shoot these people.” So they simply told the three boys to run. They took off in different directions and Landwirth never saw the other two again.

The wounds on his head and legs were becoming infected. Every step was agony but he kept going anyway. He wandered, stealing food and clothes when he could, and eventually made it to Czechoslovakia. He fell asleep in an empty house, not certain if he was going to live until morning. He was found by a woman who told him the war was over. He didn’t believe it at first and she turned on the radio, which was broadcasting the news. He began to cry. He was finally safe.

The woman and her husband took him into their home and brought doctors. They managed to save his legs and told him it would have been hopeless if they had waited just a few more hours. They diagnosed his nervous breakdown and recommended peace and quiet. He realized how terrible he looked when he finally got a chance to see his reflection in the mirror. The prisoners around him had looked much the same and he figured they had simply gotten used to it. After several weeks of recuperation in his benefactors’ home, he was ready to find out if his mother and sister had survived. It was hard for him to leave but he traveled to the Missing Persons Center in Krakow to see what information they had.

A Life Of Vengeance

Arriving in Krakow, he found a job in a dentist’s office and spent much of his spare time in the Missing Persons Center. While there, he encountered a woman who looked familiar, so he shouted his mother’s name at her.

“How do you know that name?” she asked.

“She was my mother.”

“I am Mrs. Zawuska. Your mother was my best friend before the war.”

They chatted for a while and he told her he was working at the dentist’s office. They parted ways with Landwirth feeling more hopeful. She sent a limousine to pick him up so he could come live with her. It had been so long since he used a knife and fork that they had to show him how. He was not completely recovered from his injuries and he got some much-needed peace and rest. He encountered a Polish girl who had been an Olympic swimmer and she told him the fate of his mother. The Nazis had loaded a boat with about a thousand prisoners, including his mother, and then blown it up. The Polish girl was the only survivor.

He found hope when somebody told him they had seen Margot. Over the Zawuskas’ objections, he hitch-hiked back into Germany to the village where she was living. He got directions to a house where several women were staying and whistled in a secret code Margot would recognize. He heard an answering whistle. They were reunited on their eighteenth birthday.

There were still a lot of former Nazis around and, while Landwirth wandered, the need for revenge grew. He would beat up any Nazi he encountered. He helped Allied troops round up Nazi sympathizers, showing no mercy when they begged. Then, he encountered a German boy dressed in the uniform of Hitler’s youth organization. Landwirth demanded that he strip off the uniform and threw it into the river nearby. He felt an irrational urge to strangle the boy. He could see the fear in the boy’s eyes and something stopped him. He realized that he did not want to be like them. It would be a long time before he could say he no longer hated Germans, but he was able to take the first steps to overcome what the Nazis had done to him.

He took up with an underground movement that was helping to smuggle Jews out of Europe. He hoped to smuggle his sister out of Germany and into Belgium, but was caught and thrown in jail. A friend discovered his situation and contacted his Uncle Herman, who lived in Belgium and agreed to take him in. He and his sister made it there in the back of a truck belonging to the Belgium army and he got a job in his uncle’s factory, learning how to cut diamonds. It was tough dealing with many of his co-workers, many of whom had been Nazi sympathizers during the war. His Uncle Herman became attached to him and wanted to adopt him, but Landwirth refused. Herman didn’t have much to do with him after that.

Landwirth was still dissatisfied and restless. Life on that side of the Atlantic Ocean was miserable and he began to contemplate the advantages of a fresh start. A friend gave him $20 and he worked for passage on a cargo boat going to America. He also took along an old Torah and, with that and the clothes on his back, he came through Ellis Island.

America

Although he didn’t speak much English, he found a job in New York City, cutting diamonds. He learned that the American diamond industry valued quantity over artistry. He also connected with relatives, who gave him a place to stay and helped him with the language.

It wasn’t long before he received a letter with the signature of the President of the United States of America. At first, he thought it was just a welcome to the country. Then, he realized he was being drafted! The U.S. had entered the Korean War and needed infantry. In a stroke of luck or one of the miracles he would come to believe followed him throughout his life, somebody found out that he had experience cutting diamonds and gave him the job of cutting crystals for field radios. He went from there to becoming a telephone installer and repairman. It caused him some trouble with his supervisors. He hated heights and couldn’t climb the poles without getting dizzy. He had to tell them he couldn’t drive when they tried to send him for supplies. They thought he was just coming up with excuses and told him to do it anyway. He ended up putting the truck into reverse and backing into the radio shack. They were not happy about it and gave him dishwashing duty. He could only think that at least he wasn’t on the front lines in Korea. He had seen enough of the horrors of war. For all the trouble, he managed to make it through two years of military service and was honorably discharged.

It paid off for him. He had no real wish to stay on as a diamond cutter, especially if it meant staying in New York City. He found a job in a hotel, decided he liked it enough that he wanted to move up in the hotel business, and used his GI Bill benefits to study hotel management.

Miami Beach

1954 was an important year for Henri Landwirth. He met and married Josephine Guardino and moved to Miami Beach, Florida. After working in a department store for a while, he found a job at the President Madison Hotel. It was a mess. The night manager was an alcoholic who basically let Landwirth take over his job without a raise in pay or any credit. Whenever somebody didn’t want to work, they would call him. He only put up with it because he wanted to learn the business. He learned how not to run a hotel.

Eventually, he got sick of it and partnered with a friend who had a recipe for southern fried chicken. The restaurant they opened would have been a good business, if only they could get people to come eat there. He finally hung it up when he ran out of money to buy staples with. He took a job as a bellhop at the Fountainbleu Hotel. He made $120 a week, pretty good money for a bellhop in the 1950s. He was able to use it as bargaining leverage when the owner of the President Madison Hotel called to offer him a job as the assistant manager. It meant he would be in charge of the people who had taken advantage of him.

He took it. When the manager got himself fired for being an alcoholic, he took over those responsibilities, too. He promptly fired two men who were stealing money from the hotel by renting rooms and not booking them. He had to explain that to the owner, who took it as a sign that Landwirth was a man who could be trusted. Landwirth got free reign to run the hotel his way and tried out several ideas. He had learned that hotel management was essentially a people business, so he concentrated on keeping the customers satisfied.

In this way, he met a man named B.G. McNabb, who turned out to be General Manager for the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Division at General Dynamics. McNabb wanted to dine at the hotel’s restaurant but didn’t have the required tie. So, Landwirth loaned McNabb his tie. McNabb never forgot that and eventually got the chance to reward Landwirth for his good deed.

The Starlight Motel

Cocoa Beach, Florida, was a seedy little town best known for its bars. No hotel chain saw the use of putting a hotel there. This frustrated B.G. Nabbs, who was in charge of building the nation’s early space program and needed a place to put the families of all the workers. He decided to open a hotel of his own and named it the Starlight Motel.

He partnered with Sid Raffle, promising that the Air Force would lease 30 rooms, 365 days a year, and construction began. He didn’t like the manager Raffle found, but remembered the guy with the funny accent who had loaned him the tie. Raffle got in touch with Landwirth and offered him the position of manager, on the condition that he work on his accent. Landwirth found a professional coach who, as it turned out, wasn’t so professional after all. He backed out after only a few lessons, with the excuse that he was going to start talking funny if he kept working with Landwirth. Feeling like he had blown his chance, Landwirth told Raffle. Raffle wasn’t about to lose Landwirth and simply put him in a position where he wouldn’t have to talk to customers very much. He hired Julia Doyle to take care of the customer side of things, unknowingly founding a professional partnership between Doyle and Landwirth that ended up lasting for years.

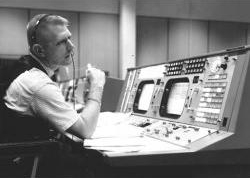

Back in those days, the Cape Canaveral people worked hard and played hard. Cape Canaveral was the place where they launched rockets; if they wanted entertainment, they could usually find a bar in Cocoa Beach. That changed when Starlight Motel opened. The motel and its bar, the Starlight Lounge, became the central hub of activity for off-duty personnel. Landwirth created a unique atmosphere with space pictures that showed up in the black lights he had installed. It fit what the NASA people were trying to do, send men into space with Project Mercury. And that’s where he met the seven Mercury astronauts.

After the first successful launch of an ICBM, Landwirth gave McNabb the keys to the hotel. McNabb threw a party so huge that the reporters from Time and Life magazines wrote articles about it. Landwirth kidded McNabb about how he was going to go broke because of all the free drinks and food but it turned out to be great publicity for the growing community around the Cape. That was the sort of hospitality that earned Landwirth a reputation for being the man to go to if they needed a host and the Starlite Motel was always packed so full that he earned the nickname of “Double-up Henri.”

The space program was one of the hottest stories in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s and the biggest names in reporting often came to town. People like Walter Cronkite, Frank McGee and Chuck von Freund would stop by the Starlight Motel and Lounge. When Chuck von Freund later died of cancer, Landwirth was one of many people who attended the memorial service at Cape Canaveral. Walter Cronkite introduced Landwirth as another good friend of his and got him to come up to the podium to say a few words.

Not everything was roses, of course. He worked long hours, sometimes eighteen hours at a stretch. This cut into his family time and would ultimately lead to a divorce. One fellow named Jerry Granger, who was also a part owner of the hotel, came in and tried to interfere with Henri Landwirth’s management. Landwirth didn’t like that too much and called Raffle. The owners talked it out, the other owners probably bought out Granger, and Raffle told him that Granger wouldn’t be interfering with him anymore.

After two years, the owners sold the Starlight Hotel and didn’t tell Landwirth until afterwards. Landwirth didn’t like the changes the new owners wanted and left to open his own hotel. His first attempt tanked. He would always suspect that a particularly cut-throat competitor had reported him for infractions of obscure regulations. He returned to Cocoa Beach and opened his first Holiday Inn. The Starlight Hotel burned down the day he opened it. The police, of course, thought it was an interesting coincidence and questioned Landwirth about it. They would ultimately rule that faulty wiring had caused the fire.

The Mercury Astronauts

One of the things about the Mercury astronauts that really stood out for Henri Landwirth was the way they let off steam. Being an astronaut was, and still is, a lot of hard work. It meant a lot of flying around the country to different contractors, training, and, too often, the sacrifice of personal and family time. Landwirth worked to make the Starlight Motel, and then the Holiday Inn, a haven for them and they promptly repaid him with rounds of practical jokes. It took some getting used to, but Landwirth quickly got into the swing of things. When somebody kidded that their wife would often greet him in the morning with a house robe splattered with eggs, he had one of his waitresses dress up in an old robe, splattered some eggs on it, and got her to take his order with curlers on.

One of the things about the Mercury astronauts that really stood out for Henri Landwirth was the way they let off steam. Being an astronaut was, and still is, a lot of hard work. It meant a lot of flying around the country to different contractors, training, and, too often, the sacrifice of personal and family time. Landwirth worked to make the Starlight Motel, and then the Holiday Inn, a haven for them and they promptly repaid him with rounds of practical jokes. It took some getting used to, but Landwirth quickly got into the swing of things. When somebody kidded that their wife would often greet him in the morning with a house robe splattered with eggs, he had one of his waitresses dress up in an old robe, splattered some eggs on it, and got her to take his order with curlers on.

He invited the astronauts to move over to his hotel whenever they were in town. They agreed, and that was when the fun really began. During one especially exuberant celebration, the Mercury astronauts ganged up on Deke Slayton to throw him, fully clothed, into the swimming pool. On another occasion, they “launched” a fishing boat into the pool for an all-night drinking party. He once caught Gordon Cooper by his pool with a fishing rod and asked what he was up to.

“I’m fishing,” said Cooper.

“You’re fishing in my swimming pool.”

“Yep.” And Cooper promptly proceeded to dump a cooler full of live fish into the pool. It was funny until fish started floating belly-up.

Wally Schirra was one of the biggest jokers and could regularly be seen trooping through the hotel with a bloody bandage on his arm, claiming that a mongoose had attacked him. This provided a steady stream of people who just had to see for themselves. The “mongoose” was actually a jack-in-the-box mechanism disguised as a nondescript animal. It would spring out when they pulled back the sheet, sending them diving for cover.

John Glenn and his wife, Annie, became two of Landwirth’s best friends. Landwirth typically wore long sleeves to hide the tattoo the Nazis had given him and, one time, Glenn asked about it. Landwirth rolled back his sleeves to show him and Glenn was sympathetic. “If I had one of those, I’d wear it like a dad-gum Congressional Medal of Honor.” Glenn was probably the most sober of the astronauts but also appreciated a good joke. Once, there were no towels in his hotel room and he went to the desk to complain. He pretended to be angry and Landwirth came over to see what was the matter. The next time Glenn checked in, Landwirth was ready for him. He stacked towels six deep on every available surface of the room and waited to see Glenn’s reaction.

He did get serious with Scott Carpenter one time. Some reporters came to town and needed someplace to put their equipment. Landwirth asked Carpenter if he minded moving, but Carpenter wouldn’t budge. So, Landwirth removed all the furniture from the room. Carpenter capitulated quickly enough though he reportedly wasn’t happy about it.

The astronauts introduced him to their lawyer, Leo D’Orsey, and he turned out to be a pretty good practical joker himself. Once, he arranged a meeting with Landwirth and the Mercury astronauts in Miami to discuss a hotel partnership. He convinced Landwirth that Jews weren’t very welcome at the hotel and he went around with a raincoat over his head until D’Orsey admitted his joke. Alan Shepard saw the whole thing and they both thought it was hilarious. Landwirth couldn’t resist getting the lawyer back for that one. D’Orsey found himself harassed by the Highway Patrol and figured out that Landwirth was the one behind it.

The jokes just kept escalating. Alan Shepard had a friend who was an alligator hunter and, once, he brought back a live one. Shepard had been looking for a good way to get Landwirth back for some joke, so he took the alligator and put it in the pool. Eventually, NASA officials realized that somebody was going to get hurt and did their best to clamp down on the more outrageous pranks.

The Adventure of the Giant Cake

The reporters Henri Landwirth knew were good people, but sure could be a nosy lot. They wanted to know why in the world there was a big refrigerated truck in front of the Holiday Inn where, not long ago, Walter Cronkite had filmed a Sunday Evening News segment. Landwirth finally admitted that there was a giant cake in there but begged them not to write about it.

And what was up with the cake? Well, Landwirth wanted to do something special to honor John Glenn’s orbital flight in the Friendship 7, so he had the cake baked and decorated to look like a Mercury space capsule. The flight went through one frustrating delay after another and Landwirth had to find creative ways to keep it fresh. It was baked in sections and they assembled it in a rented truck. When the cake began to spoil, they found an air conditioning unit. Then the chef asked Landwirth how in the world they were going to get a 900-pound cake off of the truck! The answer was to build a lift.

Making it even worse, nobody outside NASA was supposed to know what the name of John Glenn’s capsule was. Landwirth got the name from some NASA insiders anyway, though they warned him that one slip and they could all be in deep, scalding hot water. They sent him a photo in a sealed envelope and, feeling like a secret agent, he promptly put it in a safe. Project manager Walt Williams found out about it and warned Landwirth, “What you have is top secret. If word of this gets out, I’ll come after you. I promise you.” Landwirth promised that the photo wouldn’t leave his safe until after the mission was over.

When John Glenn finally made it into orbit, Landwirth called Charles Buckley, who was in charge of security at the Cape, and told his story. He wanted to bring out a 900-pound cake that had been around since before the first delay. Buckley must have thought Landwirth had cracked and threatened to have him arrested. There was no way Charles Buckley would allow Landwirth to poison VIPs with a spoiled cake. Landwirth had to agree to have the cake tested by dieticians and they declared it edible, if a bit stale.

That wasn’t Landwirth’s only plan. He got together with Mayor Kenney of Cocoa Beach and made plans for a surprise parade. The first step was to get John Glenn’s plane diverted to Patrick Air Force Base. That took quite a tall tale about the size of the parade and how they were going to make a big holiday out of it. The man in charge of coordinating the whole thing agreed. Then, it took some scurrying on both Kenney’s and Landwirth’s part to keep all their wild claims. Luckily, Kenney owned a local radio station and got the DJs to broadcast about the big event. That got the parents to let their kids skip school for a day. They called the superintendent of schools in Orange County and got the bands they needed for the parade. They also got all the county leaders to drive cars for dignitaries. John Glenn was sure surprised and got his piece of cake.

“So, how did it taste?” asked Henri Landwirth.

“Fine,” said John Glenn.

“That’s good. Because you wouldn’t believe what I had to go through to keep that thing fresh.”

“I didn’t say it tasted fresh.”

The Cape Colony Inn

At that time, Landwirth’s future with Holiday Inn didn’t look so bright. He had gone over his boss’s head to get approval for some flags to put in front of his hotel and his boss was not happy about it. So, he agreed to manage a new hotel in the area called the Cape Colony Inn and thought it would make a good investment opportunity for the Mercury astronauts. In the meantime, he was flying out to hand in his resignation with the Holiday Inn personally when he made a layover in New York City. The airport was all tied up with security everywhere. He found out that they were getting ready for John Glenn’s parade and flagged down a security officer. The officer did not believe that he actually knew Glenn. Luckily, Charley Buckley was there and dropped a bombshell. Landwirth was going to ride in the parade in the limo with Glenn’s children!

The sidewalks were packed with people and ticker tape was everywhere. He later got to have lunch with Glenn and some senators. He didn’t think anybody but John Glenn would know who he was, but no one asked what state he represented when he introduced himself.

He made a flight to Boston the next day and handed in his resignation. His idea was to make the Cape Colony Inn a haven for the media and made plans that included media rooms and a dark room to develop photography in. He created the exclusive University Club, where business leaders could meet over a few drinks, hash out differences and make decisions. He also wanted a world-class chef, so he rented an out-of-business restaurant strictly for the purpose of trying out chefs with the help of a few friends. His first pick was a failure, not because the man couldn’t cook but because he took too long to prepare food. His second choice worked out fine and the restaurant was a success.

The Cape Colony Inn also became the destination of choice for visiting dignitaries. That was often an adventure. He had to find someone who knew how to cook Indian food when the Indian Prime Minister came for a visit, and then the Prime Minister sent back his plate. He told Landwirth that too many people in India never had enough to eat and he wanted the portions cut in half. When the king of Afghanistan came to town, Landwirth had to find a throne. He looked all over Florida to find Charlotte roses for the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg. Landwirth coped by falling back on his hotel manager’s habit of simply treating people like people.

While working at the Cape Colony Inn, Landwirth pulled what would become the most famous of his pranks. Project Mercury was winding down and the astronaut corps had recently more than doubled with the addition of the New Nine. The Mercury astronauts were very much their own clique and the new guys seemed to need a little help to break the ice. So, Landwirth invited them over for dinner. The official menu included veal cutlets and baked potatoes. They found out what the unofficial menu was when they tried to eat it. Fried cardboard and raw potatoes! This was the day before Gordon Cooper’s flight, so Landwirth kept an eye on him to make certain he didn’t eat it and make himself sick. It broke the ice, all right. The New Nine teamed up with the Mercury Seven to throw that fried cardboard at Henri Landwirth. Some of the New Nine, like Pete Conrad and Frank Borman, got to be pretty good friends with Landwirth, too.

The Mercury Seven sold their interests in the Cape Colony Hotel not long afterwards. Landwirth decided it was time to leave, too. Because of a no-compete clause in his contract, this meant he had to leave Cocoa Beach. He later learned that the Cape Colony Hotel went bankrupt.

He took over the Holiday Inn in Lakeland, Florida, and promptly fired the manager and most of the staff. The manager was refusing to rent rooms to Black players on the Detroit Tigers baseball team. The rest of the staff was just plain incompetent and disrespectful to both Landwirth and the customers. It took some quick diplomacy to convince the Tigers that there would no longer be a problem with bigotry at his Holiday Inn and he got to know some of the players pretty well. He also leased a couple of Holiday Inn restaurants that were already in trouble and made a bad mistake by not reading the lease agreement. He almost lost all the kitchen equipment, which was not cheap, but managed to get in touch with a fellow called Big Ed, whom he had worked with before and was now the head of the GE Credit Union. With Big Ed’s help, he was able to keep the kitchen equipment and save the restaurants.

Property values in Lakeland were on their way up and Landwirth made his second successful partnership with the Mercury astronauts. They bought a piece of property from the City and parceled it out, neatly making a couple of million dollars between them. He opened and then sold a successful barbecue restaurant and some cocktail lounges, but all the hard work finally cost him his marriage after 13 years.

The Cerebral Palsy Clinic

While looking around for ways he could help the Lakeland community, Landwirth accepted a position as officer and director of a foundation that helped handicapped children. He was impressed by the overlooked talent in these children and opened a small nursery where they could grow and sell plants. This was the first chance many of them had to earn an income and he thought the older children would make excellent employees for his Holiday Inn. With Landwirth’s help, the children gained abilities, confidence and a level of self-sufficiency they wouldn’t have normally had. For his work, Florida gave him the Man of the Year Award. Such recognition embarrassed him at first but he soon saw the awards as a chance to help get his message out.

He also became director and then president of the local chapter of the Cerebral Palsy Clinic. With the help of local businesses and fund-raisers, they built a home and a pool for people with cerebral palsy. He thought it was wonderful that children who would have been killed on sight in World War II Germany could have something valuable to contribute in American society.

Orlando, Florida

1969 was a big year. It was the year Apollo 11 first took men to the moon, and it was also the year Henri Landwirth partnered with John Glenn and real estate agent John Quinn to open a series of Holiday Inn franchises in the Orlando area. Walt Disney World was being built and they saw it as a chance to get in on the action.

John Quinn also had a background in financial planning and secured the mortgages. Henri Landwirth oversaw the construction and would also manage the hotels. They originally planned for 200 rooms for the Altamonte Springs location and 156 rooms for Disney East. He convinced his partners to add 72 more rooms to Disney East at a time when it would be easy to do. The Disney East location was only three miles from Disney’s front gate and was usually filled near capacity.

The Altamonte Springs location was a different matter. Kids could get omelets for a dime apiece and Landwirth added a club called The Why Not Lounge. The Lounge turned out to be the only way they could keep the hotel open. Not even a gimmick involving a parakeet helped occupancy much. They ended up selling the place at the height of The Why Not Lounge’s popularity.

The three partners’ relationship was based entirely on trust. Their word was good enough and it was so thorough that Landwirth once handed John Glenn a stack of papers to sign in the middle of a dinner. Without a single question, Glenn signed every one. It was a relationship that would span more than three decades and grow into an operation that employed more than 650 people.

The Fanny Landwirth Foundation

As Henri Landwirth’s fortune grew, he began to think more about how he could help those less fortunate. He remembered what it was like to be a Holocaust survivor with nothing but the clothes on his back and the kindness of the Czechoslovakian couple who had taken in a raggedy and starved boy. He founded the Fanny Landwirth Foundation in 1980, naming it in honor of his mother. The Foundation’s goal is to help needy people and organizations, and has helped expand schools and day care centers in Israel. One of the Foundation’s first projects was called Witness to the Holocaust, which educates people about life in the concentration camps. More recently, it has made contributions to organizations like the Monique Burr Foundation for Children’s child abuse prevention programs and the Art with a Heart Children Program. It has also donated art to temples, charities and schools and provides scholarships for young students.

Giving Back to Kids

Whenever Landwirth counted his many blessings, he always included his three children, Gary, Greg, and Lisa. He stayed close to them after he and Jo divorced and, when Lisa was five years old, she gave her father her favorite doll. When they were older, they became active in charity work, including the Fanny Landwirth Foundation. Once, they visited the concentration camp in Matthausen so the kids could see what it was like. They lingered a little too long and were locked in. It frightened Landwirth, thinking they had been forgotten, but somebody found them and let them out. Greg and Lisa both married and gave Landwirth four healthy grandchildren between them.

In 1986, Henri Landwirth learned about a girl named Amy. She was only six years old and was terminally ill with cancer. Her last wish was to see Mickey Mouse and Landwirth agreed to donate the hotel room. Unfortunately, she died before she arrived, the result of too much bureaucracy. Saddened and angry, Landwirth began to think about what he could do to help kids like Amy. The answer became Give Kids the World.

Where else can you celebrate Christmas every Thursday and have ice cream for breakfast? Give Kids the World is a 70-acre magical wonderland for children with serious illnesses.

Give Kids the World

Henri Landwirth could come up with some seed money from his own pocket and the Fanny Landwirth Foundation. But, to really make something of Give Kids the World, he would need help from larger corporations. His first stop was the headquarters of Walt Disney. He met with Dianna Morgan, who agreed to help him on the spot. The Disney team produced a video for him to explain what Give Kids the World was all about. Disney World still provides free passes to the park for visitors to Give Kids the World. He also met with Sea World president Bob Gault, who volunteered to help in any way he could. Gault got his marketing department to help design brochures and a logo for Give Kids the World. Encouraged, he also approached the Mercury astronauts, Walter Cronkite, and Art Buchwald. They all promised to help.

The momentum began to increase. He flew to New York City to pick up a $75,000 check from Equitable Insurance Company and happened to spot Wellington Hotel. It was the first hotel he had ever worked in and he contemplated how far he had come since then. He also got commitments from local hotels to house children. He considered paperwork and the time needed to process it to be the biggest enemy of those sick kids. Instead of contracts, he went by verbal agreements whenever he could. Landwirth started out bringing kids to Florida to visit parks like Disney World and Sea World, and demand got so huge that he started planning a fairy-tale resort for children with serious illnesses.

During the planning phase, he told his secretary he would be gone for a few weeks and never went back. That ended his active participation in the hotel business. He bought some land and again found himself working long hours. It took its toll and he had to step back and take a brief rest. Hundreds of people, representing many different construction companies, volunteered on weekends to help. Company presidents and secretaries worked beside plumbers and electricians. Unions volunteered labor even though it wasn’t a union job. One volunteer told Landwirth that he had never missed a Saturday tee time in his life. On that particular Saturday, he whacked only one golf ball and went back to work. Landwirth considered it a sign of one of the best parts of America, the spirit of volunteerism. It went so well that they were able to start receiving guests in the first of their villas in the winter of 1989.

Holiday Inns was already a supporter, and their president brought Donald Smith, chairman of Perkins Family Restaurants, out to see the nearly finished facilities. By the time they left, Smith promised to donate ice cream and meals for the families. Budget Rent-A-Car chipped in $150,000 to help build the Gingerbread House, where children could eat, and companies and individuals donated decorations and tables. Perkins is still a supporter of Give Kids the World and runs a Round Your Check Up program to help pay for the food sent to Give Kids the World. Any money remaining at the end of the year is donated to Give Kids the World.

One of Landwirth’s biggest rules was that he didn’t want flashy advertising everywhere. He passed on several corporate contributions because of it and also earned the respect of several who recognized that Give Kids the World is strictly for the children.

If you are planning a trip to Florida, be sure to visit GKTW.org and find out how you can volunteer so you can see the wonderful work they do.

Give Kids The World

Visit Give Kids the World to learn more about how you can help wish kids, volunteer or donate to this amazing organization. It’s pure magic; some of the stories I’ve heard involve kids who got out of their wheelchairs and ran while at the villa.

Read More About Henri Landwirth

Give Kids The World Collectibles on eBay

[ebayfeedsforwordpress feed=”http://rest.ebay.com/epn/v1/find/item.rss?keyword=%28henri+landwirth%2Cgive+kids+the+world%29&sortOrder=BestMatch&programid=1&campaignid=5337337555&toolid=10039&listingType1=All&lgeo=1&feedType=rss” items=”10″]