Kalpana Chawla

At the age of three years old, a young lady was preparing to attend school in Karnal, India, when she chose the formal name of “Kalpana”, meaning “imagination”, from three possible choices. She had been born on March 17, 1962, but this ambitious girl insisted on lying about her age so she could enroll in school early. Her parents, Banarsi lal and Syongita Chawla, had settled in the Model Town area of Karnal and then moved to Kunjpura Road, where her father worked his way from post-Partition poverty to the owner and operator of successful businesses that included a manufacturer of steel chests, a cloth store and a tire factory.

Kalpana Chawla enjoyed bossing around younger cousins. Her mother, a liberal-minded woman who had fled Pakistan after Partition, encouraged her to follow her dreams though there were hints that she would have liked Kalpana to give her some grandchildren.

Kalpana was not the only one in her family to buck Indian tradition. She also had an older brother and two sisters who chose their own paths. Sunita, often called “Pikki” by her family, attended college and became a financial analyst. Rather than submit to an arranged marriage, she insisted on holding out for a husband that could meet her own standards. Through her eventual husband, an Indian navy officer, she was later able to arrange tours of one of the Navy’s few aircraft carriers for family members. Kalpana got a few surreptitious photos during these tours. Kalpana hero-worshiped Sunita and the two sisters remained close for all of Kalpana’s life.

Her younger sister, Deepa, became involved in fashion design and art, earned BA and MA degrees and married into a business family residing in New Delhi.

Kalpana hadn’t been too sure what she wanted to do with her life as a young girl. She was an avid reader, interested in studying the lives and art of Picasso and van Gogh, and also liked to entertain children with made-up stories. Relatives remembered that she couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket, so singing was out. Sports was less of an aptitude though she was able to regularly win games of badminton against family members. At one point, she considered becoming a newsreader for All India Radio. Since watching airplanes at the local airport, and then watching her brother earn his Private Pilot’s license, she developed an interest in aerospace and flying. In tenth grade, she decided that was what she wanted to do with her life.

When she enrolled in Punjab Engineering College at Chandigarh, she was told that aeronautical engineering was not something that girls studied but became the first woman at the college to major in it anyway. She made friends with her classmates and, when she became an astronaut, invited two of her professors to attend her launches. As a woman engineering major, she was not universally popular and sometimes older students tried to haze her. She shot back at one particularly persistent bully, “What are you going to do, hit me?” She was taking karate lessons and could likely have knocked him flat if it came to a fight. After that, the hazers pretty much left her alone.

Upon graduation, she accepted a position as Lecturer at Punjab Engineering College. She had already set her sites on enrolling in an American college to earn her Master’s degree. She was accepted into a few universities and chose the University of Texas at Arlington, which also offered an assistantship program to help with tuition. Such assistantships were usually reserved for students who had attended for a semester but they made an exception for Chawla based on her previous academic performance. Getting her father’s approval took some convincing and plenty of support from her mother and sister, but her persistence paid off. She rarely took advantage of her family’s fortune while in America, and then only to help with basic expenses or to help a friend who was having difficulty buying textbooks.

Receiving her student visa was another hurdle. Chawla had no trouble getting a passport but staffers at the U.S. embassy occasionally admitted to laziness and denying visas for no good reason. Chawla took advantage of mutual friends to find a trustworthy person who could be counted on to check her credentials and was approved.

The first time her future husband, Jean-Pierre Harrison, saw her, she was sleeping on the floor of her apartment. He generously offered to provide a bed. It turned out that she had only fallen asleep on the floor from pure exhaustion. He was struck by the fire in her eyes. This was obviously a woman who was going places. He was training to be a professional pilot and connected well with both Kalpana and her brother, who had his private pilot’s license. Kalpana took a ride in his airplane and, though she enjoyed the ride, had some difficulty hearing over the engine noise and couldn’t answer a question he asked. He later gave her a camera as a birthday present and the both of them got a lot of pictures with it.

Being an Indian in America could be a challenge at times. As a vegetarian, Chawla was often limited in her options while eating out. Harrison helped by learning how to cook Indian dishes though his attempts at experimentation usually weren’t successful. When they traveled, pizza, salad, potatoes and bread were usually on the menu unless they were lucky enough to encounter a good Indian restaurant.

Western entertainment was also occasionally baffling even though her English was improving. She never saw the attraction of soap operas and Harrison agreed that they were a waste of time. She once mistook an advertisement for a flying circus as an air show. She liked the TV show Rifleman for its strong lead character. She also took to Ayn Rand and stories of the old American West. When she began following American movies, she developed a dislike for John Wayne when he criticized a colleague for taking the part of van Gogh in Lust for Life.

One thing Harrison and Chawla had in common was a sense of humor. They often tested each other’s gullibility and Chawla once had Harrison convinced that she had wooden teeth. When they argued, she often gave him a variation of “You’re so stupid!” and regarded any dissenting opinion as an “atrocity”. After reading Oriana Fallaci’s book In a Man, she often told Harrison to “Calm down, Alekos,” whenever he got wound up.

A visit from Chawla’s father was enough to convince him that Harrison’s intentions were honorable. Banarsi slept at Harrison’s apartment due to insufficient room at Kalpana’s. Once, Harrison had to apologize to Banarsi over the drunken behavior of a visiting friend and had a firm discussion with the friend. Harrison also took Banarsi flying, something that the older man thoroughly enjoyed even though he kept requesting risky maneuvers. When Banarsi returned home, he was happy to report to anyone who asked that, while it was unusual for an Indian woman to be courted by a Westerner, he was satisfied with Harrison’s conduct.

Eventually, Harrison began to teach her how to fly. Chawla knew that flying was risky. Once, she claimed to have seen an aileron fall off a glider in flight, which would have created a highly hazardous situation. That didn’t always stop her from taking risks. Harrison found that he had difficulty maintaining a dispassionate attitude about teaching her and suggested that she find another flight instructor. It took some time due to an occasionally hectic schedule, but she did obtain her private pilot’s license.

By the end of 1983, Chawla and Harrison were discussing marriage. They wanted to keep the situation a secret from Chawla’s family for as long as possible. Her father might want to follow tradition and arbitrate the match. It took some courage, but on December 2, 1983, they went to a courthouse in Fort Worth, Texas, where they coached a Justice of the Peace in pronouncing Kalpana Chawla’s name and were married in a civil ceremony. The Justice pointed out a vintage marriage certificate on his wall to illustrate the importance of their new commitment. They took the point that it was for life.

For the time being, they were content to maintain the illusion of separate lives as friends even though visiting relatives may have suspected that something was up. Harrison helped Chawla with her thesis project, a study of a cross-flow fan embedded spanwise in an airplane wing. Her thesis advisor was impressed by her stamina while working in a laboratory that lacked air conditioninng. She received her master’s degree and moved to Golden, Colorado, with Harrison. While there, she took classes at the University of Colorado and earned a doctorate in aerospace engineering.

Finally, Chawla admitted that they were married during a visit to India. She admitted to Harrison that her father had sulked for a week before accepting it.

Chawla was ambitious and not afraid to do what it took to obtain a goal. She had role models to suit, including Abraham Lincoln, Charles Lindbergh and Lewis and Clark. She was smart enough to decide on the most effective and practical way to obtain a goal. She also enjoyed working with her hands and, when she got her driver’s license, she frequently made small repairs on a used AMC Hornet she bought.

Neither was she afraid to stick up for herself if she saw something as unfair. She once went toe-to-toe with a professor who gave her an undeserved “F”, taking the conflict up the chain all the way to the university president. She briefly spoke with a lawyer who refused to take the case. While she did not prevail, she was happy to report that the professor looked very nervous during this time and got an “A” in every other class.

Having an adventurous side, she learned how to SCUBA dive while at college. She was not a strong swimmer, but she got by with only the occasional scare and Harrison was usually right there with her to help if she ran into a problem. He did try to help Chawla improve her swimming skills but didn’t get much farther than helping to improve her confidence. Later, while training to become an astronaut, she would take swimming lessons on her own time several times a week.

Hiking was another hobby. Chawla was a longtime nature lover and enjoyed visiting parks across America over the years. While hiking along Boulder Creek, she once decided to see what would really happen if she touched her tongue to a frozen metal pole. Luckily, she came away without too much damage to her tongue. It wasn’t unusual for her to wander off the trails to inspect natural elements, occasionally encouraged by a friend who was a nature hobbyist. On the flip side, she wasn’t too impressed by the New York skyline and missed the tranquility of the outdoors whenever she was in a big city.

When Challenger was lost in January 1986, Kalpana Chawla was at the University. Harrison called to give her the news Her initial response was, “I was wondering why someone had placed a rose next to Ellison Onizuka’s name” on a wall containing names of alumni who had become astronauts. Ellison Onizuka was one of the mission specialists on that tragic flight.

Kalpana barely batted an eyebrow at the reminder of the risks involved with being an astronaut. She was already considering applying for the NASA astronaut corp, which required her to be a U.S. citizen. When she applied for permanent residency as one of her first steps, the inspector from the Immigration and Naturalization Service wondered aloud why she had waited so long. She already met the requirements and easily obtained her residency.

In due course, she received her Ph.D. in aerospace engineering and went to work for one of NASA’s contractors as a research scientist in the Computational Fluid Dynamics Group. She worked at the NASA Ames Research Center in Sunnyvale, California. The move was somewhat bittersweet because she was leaving the beautiful vistas of Colorado, but she was excited about starting a new chapter in her life. Her first encounter with the rules and regulations in California led her to exclaim, “They’re all Commies!” She adjusted readily enough and was assigned to a project that simulated airflow around a delta-wing descending vertically using vectored thrust. The project ended too soon for her taste, especially when she found out that she was listed as one of the primary researchers.

She joined a local flying club and began her aerobatics training. While there, she did encounter the occasional cultural misunderstanding that included some cheeky boys asking whether the bindi, a red dot that some Indian women wear on their foreheads, meant that they had been shot. She only laughed. Encounters like that were usually minor and did not stop her from adding to her ratings as a pilot. By the time she left California, they included a Commercial Pilot License for single- and multi-engine airplanes, seaplanes and gliders, along with Certified Flight Instructor ratings for single-engine airplanes and instrument-airplane. She did try flying helicopters but decided she didn’t like it.

Chawla finally became a U.S. citizen on April 10, 1991. She had been conflicted about giving up her Indian citizenship but decided it was necessary if she wanted to pursue her dreams. She did keep her now-invalid Indian passport and also obtained a visitor visa from the nearest Indian Consulate.

She was not always fond of politicians, but she approved of Clinton’s choice of Al Gore as a vice presidential candidate. She liked Gore’s stance on environmental issues. By the time Clinton went to the White House for his first term, Chawla had become vice president of a four-person company called Overset Methods, Inc. This company provided computational fluid dynamic services for NASA Ames. All four members of the company had experience with this work and were now doing it under their own banner.

When NASA announced that they were looking for new astronaut candidates on June 1, 1993, Kalpana Chawla was ready with her paperwork. She went through the process and actually made it pretty far, but didn’t make it in that round. She was disappointed but didn’t let it discourage her. She tried again in the summer of 1994. The medical routine was thorough enough for one of the doctors to guess that she was vegetarian. She learned that she had made the cut in December 1994. Friends and family kept her phone line busy for the rest of the day.

Finishing up her work at Ames, Chawla was often interrupted by reporters wanting interviews. One friend suggested, rather cheekily, that she capitalize on her fame with a “Kalpy doll” that looked like a Barbie doll in a spacesuit. It was tough not to let her sudden celebrity go to her head. Drawn by her new status as an astronaut, she left California for Houston in March 1995.

Once she got to Houston, she found out that being an astronaut wasn’t necessarily easy. She barely had time to settle in before training began. This often meant traveling across the country as she and the rest of her astronaut class visited various NASA and military centers. She became rated in the T-38N and studied the space shuttle system and systems being developed and built for the International Space Station, civil service regulations, and public relations. Training for Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA) proved a challenge because she was so petite that NASA had no EVA suits that would fit. She took survival training and adopted a regular fitness regime for the first time in her life. In keeping with astronaut tradition, the new astronaut candidates (ASCANS) were dubbed “the Slugs” by the previous class. One French member of the Slugs came up with a better name, the “Flying Escargots”. That was the name that stuck.

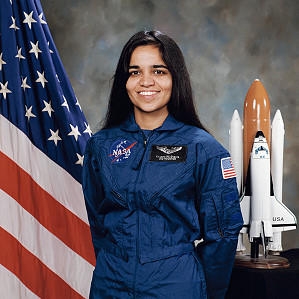

Chawla picked up the name of K.C. from some fellow ASCANS who had trouble pronouncing her name. Her husband, Harrison, did not take to the suggestion that he socialize with other astronaut spouses and enrolled in the University of Houston Clear Lake as a Computer Science major. He had been a flying instructor but thought it was a good idea to explore a new career. He did help Chawla choose an official NASA photo.

With so many high-powered, alpha-dog personalities around, Kalpana Chawla found out fast that her tendency to micromanage wasn’t always appreciated. When she tried to extend her reach to areas that she knew little about, she could get snipped at: “You can’t know everything!” She gradually backed off.

She occasionally became irritated with the attitude of others, as well. She recalled one astronaut who irritated ground personnel at an El Paso airport by frequently requesting a particular brand of tortilla when he made stopovers for refueling. Her irritation never lasted long, though. The families of the STS-107 crew remembered her ready smile, intelligence and steady personality that made her good with their kids when she could find a break from training.

As graduation from basic training approached, she was assigned to a position that made use of her mathematics and computing skills. Some of the topics like the development of new control software for the space shuttle were a little beyond her, but she learned as much as she could and made valuable contributions. In November 1996, she was selected for the STS-87 crew as Mission Specialist 1 and backup Flight Engineer for ascent.

The STS-87 crew included Shuttle Commander Kevin R. Kregel, Pilot Steven W. Lindsey, Takao Doi from the Japanese National Space Development Agency, Leonid K. Kadenyuk from Ukraine, and Winston E. Scott. Kregel was apparently a lackluster leader whose tendency to make snide remarks undermined his own efforts at team-building. Lindsey developed a friendship with Chawla and enjoyed getting into contests with her to see who could come up with the wittiest retort. Kalpana Chawla also developed a good working relationship with Kadenyuk, who came to rely on Chawla for help with both procedures and the English language. Winston Scott was usually all smiles but could also be prickly. He had majored in music but gravitated towards aerospace engineering while in college and was also a Naval Aviator. Takao Doi was a longtime resident of the U.S. who had taught at the University of Colorado. While the crew never developed a tight bond, they remained professional.

One incident involving U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright did irritate her, mostly because it interfered with training and began a long fight with politicians and government officials. Albright requested that Chawla tape a video message for the Indian parliament. Concerned that her name would become misused by the selfish ambitions of career politicians, Chawla refused and Kregel backed her up. Eventually, they compromised and the entire crew became involved in the video. Chawla’s part was minimized as much as reasonably possible to avoid her name and face being misused and it made the State Department happy.

Shortly before the scheduled launch, the crew went into quarantine at the Johnson Space Center. Immediate family members were permitted to visit if they had been screened for infectious illness. Chawla commented on the plain food but otherwise was focused on final preparations and training for the flight. They flew in T-38Ns to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida a few days before the flight.

On November 19, 1997, STS-87 launched right on schedule at 2:46 pm. Chawla grinned when she felt Columbia‘s external tank engines ignite. Columbia reached orbit eight minutes later. Kregel and Lindsey performed a series of maneuvers that resulted in a more circular orbit and Chawla later commented that the sound of the engines firing sounded like cannon fire.

During the first couple of days, Kalpana Chawla noted the usual effects of adjusting to space flight: a puffy face, a constant feeling of falling and a bout of insomnia. One of her duties included using the Columbia‘s robotic arm to deploy the SPARTAN satellite for independent operations. Due to a malfunction and a fellow crew member’s failure to follow a backup procedure, the SPARTAN wouldn’t behave. Chawla attempted to return it to the cargo bay, but the glare of the sun got in the way and she accidentally bumped it with the arm, causing a wobble. The attempt was abandoned for the short-term. Three days later, Scott and Doi made an EVA to manually retrieve SPARTAN. Its operation seemed normal, but controllers on the ground decided against redeploying it. Chawla unfairly took most of the blame for SPARTAN’s failure in the press. The reality was that extenuating circumstances were largely at fault.

Despite the problems and occasional minor annoyances that included Kadenyuk drinking all her tea, she was enjoying her time in space. During the flight, she spoke with Indian Prime Manager Inderjit K. Gujral. She was reluctant to be the center of attention, especially if it meant possibly being used as a political prop. Most of the crew stayed out of the way though she did snag Lindsey to introduce him. Gujral mostly seemed interested in Chawla but did invite the crew to visit. The crew visit never happened due to strained relations between the U.S. and India.

She also had a chance to hold a conference with her family during the flight and showed off microgravity acrobatics to her family, which was visiting Houston at the time. Other than the failure of SPARTAN, the mission was a success and Columbia touched down on December 5, 1997. The crew walked around the Columbia for an external inspection. Chawla later commented that the Columbia‘s bottom looked like it had been shot full of bullet holes. Foam had flown off the external tank during launch, damaging the lower surface.

Like the rest of the crew, Chawla spent the next couple of weeks regaining her equilibrium. Microgravity can confuse astronauts’ sense of balance and she ran the risk of falling if she moved her head too quickly. During the usual round of briefings and public appearances after the flight, crew members emphasized that the issue with SPARTAN was under investigation and the issue eventually faded from public memory.

Chawla was once again irritated by politicians, this time a Punjab candidate who was running for office and wanted a statement in support of his campaign. The employees at the Johnson Space Center helpfully did not speak Hindi, drawing complaints from the secretary to the Governor of Punjab that he couldn’t get in touch with Chawla. When her visiting father picked a bad moment to insist that she translate technical documents right after she had argued with officials, she flatly refused.

Traveling internationally proved to be as much of a challenge as traveling in America was. Difficulties included a tight schedule and the arrangement for vegetarian meals at official functions. When a representative of the Indian embassy in Japan suggested that Chawla attend a separate function, he was asked to check with the Japanese officials who were running the show. That idea was dropped.

Finally, the crew landed back in Houston. When legendary astronaut Alan Shepard died in 1998, Kalpana had the honor of acting as one of the ushers at a memorial service. There was one older fellow who kept getting out of line and Kalpana insisted that he follow directions. She did not realize until afterwards that the fellow she kept correcting was Neil Armstrong.

In September of that year, Chawla and a few other members of the STS-87 crew visited Ukraine. By this point, she had forgiven Ukrainian native Kadenyuk for drinking her tea. In a whirlwind tour, they met President Leonid Kuchma, who handed out medals. They also visited the National Academy of Sciences, which gave a presentation of some of the experiments that had flown on Columbia. The mayor of Kyiv invited them to lunch and then the crew visited Dnipropetrovsk, which was most famous for hosting a formerly secret rocket factory. One of her favorite stops was an event that included a Gypsy dance, which reminded her of her hobby of traditional Indian dancing.

At one time or another during the Ukrainian tour, a lot of the crew or their families got tipsy from the custom of frequent toasts during meals. Providing suitable menus for Chawla was challenging and, at one stop, she took one look at a whole steamed sturgeon and resorted to vegetables and bread. Chawla missed out on one of the few Pizza Huts in Ukraine because of a scheduling conflict but an officially scheduled visit to a restaurant that included several vegetarian options made up for it. When she returned to the U.S., she was dismayed by the negative attitude of an immigration official who had developed a poor opinion of Ukrainians in general because a few had tried to enter the U.S. illegally.

Eventually, the schedule began to return to normal. Kalpana Chawla found time for a hiking trip with her sister and had a chance to visit the cosmonaut training facilities at Star City. Development and building hardware for the International Space Station was getting into full swing and astronauts were eager to become part of station crews. She survived the frigid cold conditions of cosmonaut survival training and returned with a Russian tea set.

In 1998, NASA accepted a new astronaut candidate of Indian descent named Sunita Williams. In February 2000, Williams and Chawla flew an airplane from Pennsylvania to Houston together. Williams had a background in Navy helicopters and Chawla had more experience in light aircraft like the Piper Super Cub. During the trip, the engine gave out while the airplane was coming down for a landing. Chawla landed safety and an investigation revealed that the magnetos that supplied electricity to the spark plugs had quit. Both Williams and Chawla swore that they had done nothing to cause the problem and the exact cause was never discovered.

During the summer of 2000, Chawla was assigned to the crew of STS-107. She was delighted to have a chance to fly in space again. The crew quickly pulled together under the capable leadership of Shuttle Commander Rick Husband. The tradition of astronaut pranks continued when Chawla’s husband, Harrison, served coffee to Ilan Ramon in a cup that had a realistic picture of a cockroach painted inside. Ramon was barely rattled. Harrison continued his needling of Ramon by coming up with a fictional essay about the music career that Ramon might have had in an alternate universe that was read aloud to the amusement of the crew.

In December, she was once again bothered by politicians. Forced to interrupt training during a visit of Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, she spent two days attending events in Washington. She was basically an ornament and hated it.

When the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, unfolded, the Johnson Space Center was closed as a potential target. Chawla got a taste of how isolated astronauts could be from world affairs when she was asked why India didn’t make a stand against terrorism. She was also critical of President George W. Bush and his performance in office, occasionally arguing with other astronauts about it.

Each astronaut could choose songs for wake-up music and Chawla’s selections included Deep Purple’s Space Truckin’. She had seen them in concert and met lead singer Ian Gillan, who requested that Harrison post updates on the crew’s training and mission on their website’s blog. After checking with NASA’s legal staff, he decided that the attorneys were too cautious and it would be okay. Another music selection was Abida Parveen’s Yaar ko Hamne ja ba ja Dekha, played on Flight Day 15.

During training, Kalpana Chawla made annotations to the space shuttle manuals that were later incorporated in revised versions. Several astronauts were complimentary of her efforts to make their job safer and easier. She never changed her habit of being methodical and very neat and Harrison would sometimes needle her by moving items on her pristine desk when she wasn’t there.

Despite Chawla’s dislike of George Bush, she did show some political savvy when they met. An official at NASA headquarters had been bothering her to interrupt training for a trip to the Asian-Pacific Island Conference in May 2002. At a White House function, she made a comment to George Bush about how Rick Husband was a supporter of his. Completely misunderstanding, Bush commented, “Please thank your husband for his support.” The NASA official backed down.

STS-107 faced a drawn-out series of delays that was beginning to irritate the crew. Finally, the crew went into quarantine and began to adjust their circadian rhythm to match the fact that they were going to work in shifts. The Red Team, of which Chawla was a member, would work while the Blue Team slept and vice versa. Security was tight. NASA had received threats from marginals who did not support the space program over the years and the 9/11 attacks had been a stark reminder that some extremists might follow through on those threats. As the launch day approached, the crew gathered for a barbecue in the Beach House that was often used for astronaut gatherings. Ilan Ramon produced a bottle of wine from Israel for a toast and the crew signed the bottle once it was emptied.

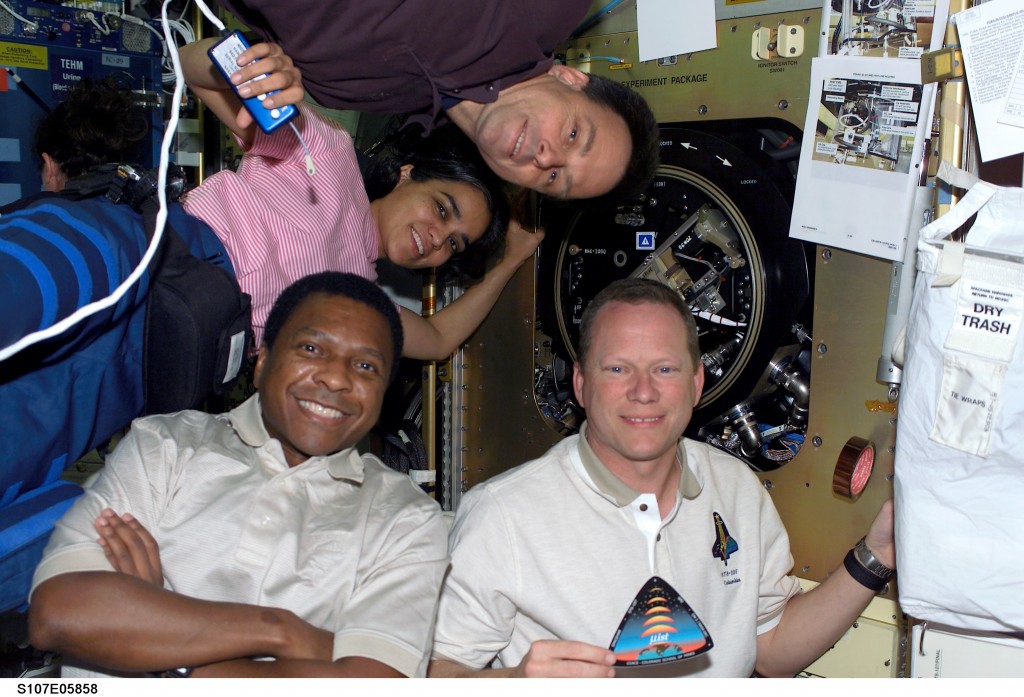

The launch occurred on schedule on January 16, 2003. As the primary Flight Engineer, Kalpana Chawla sat on the flight deck just behind and between McCool and Husband. Once necessary adjustments to the orbit were made, the two shifts settled into the intense schedule of performing 80 experiments in 16 days. When she got time to conference with her family over a TV link, she demonstrated the wonders of microgravity by performing tumbles and catching treats with her mouth.

Chawla might have remembered how the bottom of Columbia looked like it had gotten shot at during STS-87 due to falling debris from the External Tank, but none of them realized that the Columbia‘s exterior had taken serious damage this time. Ground troops considered having somebody do an EVA to check for damage, but none of the crew were rated for it. After some debate, they decided that it would not be an issue. It turned out to be a fatal mistake.

During reentry, Kalpana was sitting in the same position on the flight deck. As Flight Engineer, she would have been among the first to notice a problem. The left aileron trim was deflecting more than necessary to maintain the required roll attitude. She alerted Rick Husband, who was focused on his own job and acknowledged her warning. The trim began to approach its limits and the orbiter began to yaw to the left. While Husband and McCool wrestled to maintain control, hydraulics lines began to fail and the orbiter began flying belly first. By this point, Houston controllers also knew there was a problem and tried contacting Columbia. The radio gave out just as Husband acknowledged, and then the Columbia disintegrated. The crew must have lost consciousness when the cabin ruptured, too quickly to react.

Nothing that Kalpana Chawla had on board Columbia remained intact, though the NASA employees responsible for recovering debris found fragments of clothing, CDs, books and other items that were recognizable as being part of her Personal Preference Kit. Harrison distributed many of these items to their intended recipients but resisted attempts by museums to solicit donations. He also wasn’t impressed by coverage provided by the media as a whole. After the initial rush, he also avoid most events commemorating the Columbia accident and turned down most requests for interviews. Once he dreamed that he was talking to Chawla and asked her where she was. She responded, “At the edge of time.” He later wrote a biography with a similar title.

[ebayfeedsforwordpress feed=”http://rest.ebay.com/epn/v1/find/item.rss?keyword=%28space+shuttle%2Cspace+shuttle+astronauts%2CNASA%2Ckalpana+chawla%29+-%28optical%2Csunglasses%29&sortOrder=BestMatch&programid=1&campaignid=5337337555&toolid=10039&listingType1=All&lgeo=1&feedType=rss” items=”10″]