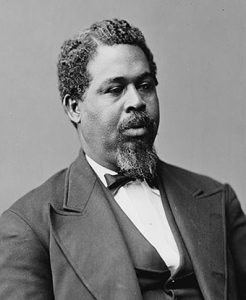

Scott Carpenter

One of the Mercury Seven astronauts and member of the Sealab II crew, Scott Carpenter was the second American to orbit Earth in the Aurora 7 and the first to claim the dual title of Astronaut/Aquanaut. Although he wasn’t always popular with some of the well-known names of the early space program, he remained an active advocate for space exploration and protecting the ocean.

One of the Mercury Seven astronauts and member of the Sealab II crew, Scott Carpenter was the second American to orbit Earth in the Aurora 7 and the first to claim the dual title of Astronaut/Aquanaut. Although he wasn’t always popular with some of the well-known names of the early space program, he remained an active advocate for space exploration and protecting the ocean.Train Trip to Colorado

Malcolm Scott Carpenter was born in New York City but he and his mother moved out to Colorado when he was two years old. Florence Carpenter had been diagnosed with tuberculosis and told that she had to leave New York City to recover. Young Scott Carpenter – he would stop using the name of Malcolm when he reached adulthood – was, naturally, excited by the chance to take his first train trip. His father, a chemist, remained behind in New York City, pleading studies and work. Like many long-distance relationships, this one fell apart and Scott Carpenter’s parents would eventually divorce.

Malcolm Scott Carpenter was born in New York City but he and his mother moved out to Colorado when he was two years old. Florence Carpenter had been diagnosed with tuberculosis and told that she had to leave New York City to recover. Young Scott Carpenter – he would stop using the name of Malcolm when he reached adulthood – was, naturally, excited by the chance to take his first train trip. His father, a chemist, remained behind in New York City, pleading studies and work. Like many long-distance relationships, this one fell apart and Scott Carpenter’s parents would eventually divorce.

Though his mother was ill and his father was mostly absent, Scott Carpenter lived with his mother’s family and had a big back yard to play in. He did as much as a young boy could to help his mother get better and his grandmother put him in charge of feeding the chickens and weeding the garden. He wasn’t always fond of the chores but became so attached to one rooster that, when his mother suggested getting rid of it, he came up with the perfect fib. He told his mother that the rooster had laid an egg in his hand. He had remarkable eyesight, later measured at 20-10, and could zero in on a piece of lint across the room. The high altitudes of Boulder would also serve him well in later life.

In the absence of his father, Carpenter found a father figure in his Grandpa Noxon. They often took walks together and Noxon taught Carpenter many of the skills that the old frontiersmen had known, ranging from sharpening a pocketknife with a whetstone to making a trap. His grandfather also gave him his first job, folding newspapers and acting as a gofer in his print shop. He was introduced to “gotchas,” practical jokes, while working in the shop. Other workers would send him for left-handed monkey wrenches or striped ink.

He enjoyed exploring the outdoors, first on foot and then on his pony, Candy. Candy was a hard girl to catch but otherwise a fine pony for a young boy. He also got into a little more than his fair share of mischief, something that would later annoy him as an astronaut when Life magazine included that fact in a feature article. He liked to climb rocks and, on his father’s rare visits, they would have acorn fights, one-sided affairs that often ended with the young Carpenter sliding down his father’s leg.

A mile south of the Carpenter family’s headquarters, the U.S. Army began building Lowry Air Field. This brought the new and interesting subject of airplanes into conversations. Scott Carpenter received a toy airplane as a gift and that sealed his choice of careers. He was going to be a pilot. The very first pilot he met was patient with his questions and explained that airplanes only looked small when they were in the air.

As America’s entry into World War II appeared more inevitable, Carpenter became determined to join the Navy as an aviator. His father did not support his choice of career and gave his blessing only after a great deal of persuasion from both Carpenter and his mother. He was accepted as an aviation cadet after his graduation from high school.

V-12a Program

Scott Carpenter arrived at the Twelfth Naval District Headquarters in San Francisco on a 1943 Saturday morning. It was in a neighborhood used to catering to sailors and Carpenter was impressed by its toughness as he explored. He passed the physical and mental exams with no problems. The sea-level atmosphere supercharged a young man used to the high altitudes of Colorado and he sprinted from his hotel to the Western Union to send his mother a wire after being sworn in.

He entered the V-12a program the Navy had designed due to a backlog of aviation recruits. For him, this meant a few semesters of college along with his training. He went back to Boulder, signed up with Colorado University, and bought a Ford V-8 for $200. He drilled with other V-12 recruits, worked two jobs and won a regimental wrestling championship. He frequently came home exhausted at the end of the day. The effort paid off when he successfully completed preflight training.

He went out to Ottumwa, Iowa, for primary flight training. One of his very first “accomplishments” was to break his foot while showing off his trampoline abilities to a date. Flying the airplane used to train aviation students, a bird that earned the nickname “Yellow Peril” for perhaps being a little too dangerous for students, proved counter-intuitive for Carpenter, who had grown up sledding. He had to readjust his thinking on which rudder to use to correct its tendency to drift during takeoffs. He got the hang of it but World War II ended before he graduated from flight training.

He went back to Colorado University, which gave him credit for his V-12 training and made him a junior. He majored in Engineering but had no real plans for a future. He spent a lot of his extra money on his Ford, all of which went to waste when he got into a near-fatal accident. He took a curve too fast and went off an embankment. He would have died right then if a passing Navy couple hadn’t spotted him and taken him to the hospital where his mother had a part-time job.

While he was still recuperating, he met a fellow Colorado University student named Rene Price in the college bookstore. She was an energetic young woman who wasn’t afraid to occasionally flaunt society’s standards, once shocking her high school’s community by inviting a black couple to the Spring Dance. She had a past very similar to Carpenter’s, with an absentee father and a mother with tuberculosis who had moved to Boulder for health reasons, and something just clicked. It wasn’t long before they were planning a future together.

They got married, survived the record snowfall of 1948-49, and rejected a suggestion from Carpenter’s father that he go into insurance. Carpenter ran into a twist of fate when the meltoff took out a bridge, preventing him from taking an exam in thermodynamics. He would have to take the whole class again to get his degree but fate seemed to have other ideas. He found out about a promising option from the Navy called Direct Procurement. They needed engineering students and offered a commission and flight training to anyone willing to sign up. Rene had her reservations but, the more she learned about Navy traditions, the more she came to accept Carpenter’s decision to join. He loved flying in any case and the Navy’s needs came before his degree. On October 31, 1949, he reported to Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida. There, he joined college graduates like Dick Brooker and the Navy’s second African-American aviator, named Carter.

Aviator Training

Carpenter had to borrow a uniform from another ensign to get his Navy ID card, and then purchased a uniform of his own. He spent six months taking classroom courses that included celestial navigation, radio procedures and aircraft recognition. While he was still training, his wife gave birth to their first child and moved into an apartment near the base. They quickly adapted the traditions of a nomadic Navy family, never staying in one place for very long.

The Navy had recently starting using radios to aid communication between the fore and aft seats of a plane. Carpenter added his own innovation with a lip mike he could mount on his headset. This helped him save the time it would take to reach for a radio. The trainers drilled into him that most airplane accidents are caused by human error and discouraged unnecessary risk-taking whenever possible. The Korean War started while Carpenter was getting ready for his first solo flight.

He mastered the basics and moved on to training that included acrobatics, gunnery and his favorite, night flying. He could experiment with the fuel-air ratio delivered to the engine to get a long, red exhaust plume at “Full Rich” or a deep blue he could hardly see at “Lean.” He had to be careful; the engine could start to sputter from lack of fuel at “Lean.” He learned how to fly low and slow, at speeds that would almost caused the plane to stall. Once, to test himself, he kept pace with a kid on a bicycle. The kid was pedalling as fast as he could to keep up, while Carpenter was going so slow that his engine almost stopped. Then, he was ready for the final test that would make him a Navy aviator. He would land on a carrier deck. He made all six carrier landings perfectly and graduated from flight training soon afterwards.

For advanced training, he had to choose what kind of aviator he wanted to be. He could choose fighters, patrol planes or helicopters. His pilot’s ego insisted that he choose fighters but he was mature enough to consider the needs of his family. He knew what it was like to have an absentee father and wanted to be there for his children. He chose patrol planes. He was assigned to Corpus Christi to learn how to fly planes like the PB4Y-2 Privateer, a heavy bomber. The Privateer would give way to the newer and better P2V Neptune, big enough for a pilot, copilot, two navigators, and system techs who operated the electronic surveillance equipment.

Carpenter received his gold wings on April 19, 1951, and was assigned to Naval Air Station San Diego. Any elation he felt over finally being a naval aviator was dampened when their six-month-old Timmy died in his sleep. Nothing could be done and the doctors discovered a virus that had paralyzed his heart.

Korea

In the middle of November, 1951, Carpenter settled his family in a Hawaiian apartment only two blocks from Waikiki Beach and went on to join patrol squadron VP6 in Japan. He would start out as a navigator with a chance of being promoted to copilot, and then pilot. The squadron he was about to join had just recently lost an entire Neptune crew, ten men who had just disappeared from the radar above the Sea of Japan without a trace. It was just one reminder of the risks of war. If Carpenter needed a more concrete reminder, he just had to look around him. Japan was still recovering from World War II and a submarine factory with big bomb craters was in plain view.

The Neptunes were too big for carrier duty, so they made their home base at the N.A.S. Atsugi. They flew patrol, recon and antisubmarine duties and would move from Atsugi to Kodiak, and then Agana in Guam. They lost another plane and the squadron’s executive officer the day after Christmas when an engine quit and they were forced to ditch at sea. His squadron earned a Presidential Unit Citation and returned to Hawaii in mid-January 1952.

Scott Carpenter’s family threw a belated Christmas party and another son, Jay, was born not long afterwards. He learned how to spear fish, developing a fascination with the underwater world around Hawaii. His family moved into a Quonset hut a few months after his return; it was cheaper than continuing to rent the beach house and they were surrounded by other officers’ families.

A month later, Carpenter’s squadron was assigned to their second wartime deployment at N.A.S. Kodiak, Alaska. He was promoted to copilot and developed the opinion that his Patrol Plane Commander should have joined a monastery. His chief complaints included the chow and not having any shorts that fit and his attempts to get his wife to send him some Jockey shorts, size 30, didn’t meet with much success. During patrols, they would sometimes stay at the N.A.S. Adak at the other end of the Aleutian Islands. There were some Air Force people at Adak, and he would joke about showing them how to make a voice report.

Navigating that close to the North Pole was a good test of a navigator’s skills because of what it did to compasses. It was so bad that Carpenter once bragged about making it within a few miles of their mark with the compass spinning like crazy. The problem even led to him being promoted to pilot. His PPC let him try flying in the pilot’s seat for a couple of hops and he did so well that he moved “up the Chain.”

Not long after, Carpenter’s plane was in the air when something went off, blinding the copilot and startling the entire crew. Everybody had their own guess about what it was. Their gunner thought all of their guns had mistakenly fired. The PPC thought it was a gas explosion. Carpenter thought the wing heater had exploded. When they landed, they found out that a lightning bolt had hit the nose, leaving a huge dent and signs of melted aluminum.

At times, he was able to pull Russian propaganda and music on the radio. The Cold War’s temperature was plummeting and Russian spinsters accused American troops of atrocities like using POWs as targets for firing drills. Sometimes he could even catch snippets of American counter-propaganda programs transmitted in Russian, though the Russians did their best to jam those frequencies. As Christmas 1952 approached, he confessed in a letter home that he missed Rene terribly. When he finally did get home after New Year’s Day, he found out that Rene had braces when his nose had an unfortunate encounter with them. She had hoped to have them off by the time he got back.

While waiting for a new assignment, Carpenter was promoted to Patrol Plane Commander. He was the only Lieutenant j.g. PPC in his squadron and so proud of it that he wrote to his father, trying to explain the accomplishment to a man who had never been in the military. His squadron was assigned to N.A.S. Agana in Guam but the war was already over. A combination of poor morale and an eccentric skipper created a situation Carpenter compared to The Caine Mutiny. Carpenter himself had to discipline enlisted sailors for infractions like brawling when he could really sympathize with the conditions that caused them. He sent home a copy of one memo that suggested that the skipper was obsessive about neatness, right down to the proper disposition of Coca-Cola bottles. It was a relief to him when the tour was over. Even better, he was promoted to full lieutenant and a friend named Guy Howard nominated him to attend the Test Pilot School at Patuxent River in Maryland.

Pax River

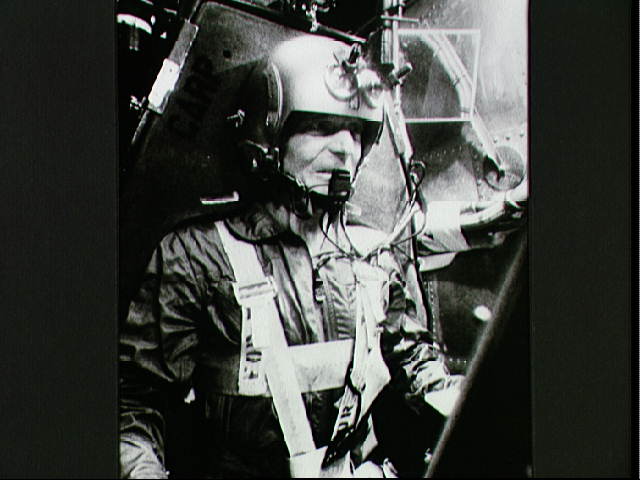

Scott Carpenter spent the next three years at Patuxent River, called Pax River for short, as part of Test Pilot Class 13. A test pilot’s job was to look for flaws in new airplanes that might have been missed on paper. It was certainly a dangerous job. Many experienced test pilots had stories of close calls and, sometimes, there was a fatality. But it was vital. The U.S. and the Soviets were already in a race for supremacy in the air. Many powerful people in the U.S. were complacent, though, and ignored warnings that the Soviets were preparing to take that race into space.

Scott Carpenter spent the next three years at Patuxent River, called Pax River for short, as part of Test Pilot Class 13. A test pilot’s job was to look for flaws in new airplanes that might have been missed on paper. It was certainly a dangerous job. Many experienced test pilots had stories of close calls and, sometimes, there was a fatality. But it was vital. The U.S. and the Soviets were already in a race for supremacy in the air. Many powerful people in the U.S. were complacent, though, and ignored warnings that the Soviets were preparing to take that race into space.

At last, Carpenter got to fly fighter jets. It was essentially on-the-job training. He made a few elementary mistakes like ignoring his rate of ascent dial at first, but quickly go the hang of it. His favorite was the Grumman F11F Tiger Cat, a supersonic plane that would become famous for being literally faster than a bullet. Like most pilots, he had an ego and thought he could fly just about anything without reading the manual first. He had already flown the F9F-6 Cougar, in which a pilot could help the plane slow down after landing by putting the speed brakes on. That was a big mistake in the Tiger Cat. The brakes ran into the ground, leaving a trail of smoke and orange sparks. An embarrassed Carpenter learned his lesson. Always, always read the manual.

And, like many pilots, he would pull the occasional stunt. Another favorite was the A3D twin-engine fighter. After a successful test flight, Carpenter took it into a barrel roll, a big no-no according to the manufacturer. The plane behaved but he got into some hot water with his superiors over it.

He was again flying the A3D when he received word that his daughter, Kris, had become ill and was being rushed to the hospital. He cut the flight short and landed with nearly a full load of fuel, which could also have been a mistake in the A3D. Fortunately, conditions were favorable for a landing and he rushed to the hospital. Kris lost her hair but recovered and grew a full head of strawberry-blonde hair that lightened to platinum.

Though his first love was flying airplanes, the Navy had other plans for Carpenter and they sent him to Line School in 1957 so he could become a more well-rounded Navy officer. From there, he went to the Air Intelligence School in Washington D.C., where he learned that the Soviets had just launched Sputnik. Carpenter took his boys out to see it and pointed it out, but they were unimpressed. The two young boys didn’t realize that they were seeing the dawn of a new era.

Drama on the USS Hornet

Like many military families, the Carpenters were used to moving around a lot. This time, they were driving cross country so Scott Carpenter could report for a billet on the USS Hornet. In Illinois, they had trouble finding a place to camp, so they ended up parking on a farmer’s land. The farmer was fortunately tolerant and his wife even brought out cookies and ice cream for the kids. They ended up chatting like old friends.

Like many military families, the Carpenters were used to moving around a lot. This time, they were driving cross country so Scott Carpenter could report for a billet on the USS Hornet. In Illinois, they had trouble finding a place to camp, so they ended up parking on a farmer’s land. The farmer was fortunately tolerant and his wife even brought out cookies and ice cream for the kids. They ended up chatting like old friends.

On the Hornet, Carpenter became the air intelligence officer. It was likely a major letdown for someone who had been a test pilot at Pax River. There was no actual flying involved. He just had to debrief pilots. But his life was about to change. He received orders from the Chief of Naval Operations in late January, 1959, to report to the Pentagon. No explanation; only orders to keep quiet about it and avoid speculation. This sparked some major drama with the Hornet’s skipper, Captain Marshall W. White, who could not comprehend why the CNO would have selected his air intelligence officer out of all the ones just like him in the Navy.

White let Carpenter go without a fuss that time. After all, even a Navy captain could not argue with orders from the CNO. Carpenter showed the orders to his wife, who promptly pointed to a recent article in Life magazine. The brand-new NASA was looking for top pilots to participate in Project Mercury. The description of desired qualifications seemed to fit Carpenter almost perfectly.

Carpenter still had never finished his degree and his missing heat transfer credits nearly came back to haunt him. But there was much room for human judgement in the selection process and his Navy record was so good otherwise that the selection committee chose to overlook it. They narrowed over 500 personnel file folders down to 110, which they then divided into three groups to be called to Washington for a briefing. Carpenter was in the first group and reported in on February 2, 1959.

During the briefings, Carpenter met a fellow test pilot named Bob Solliday, a member of Test Pilot Class 20 from Pax River. Solliday pointed out other members of his class, Wally Schirra, Pete Conrad, and James Lovell. Wally Schirra would become a fellow Mercury astronaut; the other two would join the astronaut corps in future groups. The candidate group would blow away the expectations of the selection committee when 75% of them volunteered. Carpenter called his wife to tell her that her hunch had been correct.

He went on to the preliminary psychological and intelligence testing that was the first step. One thing that stood out in his memory was the tough IQ tests at NASA’s temporary headquarters at the Dolly Madison house. He was describing a periscope-like device he had tested on the F9F-8P Cougar when one of the interviewers told him a similar device was being planned for the Mercury capsule. Two other interviews were conducted by NASA psychologists and Carpenter became convinced that he could have done something absolutely childish and not gotten a reaction. Fortunately for him, he didn’t.

He went on to the preliminary psychological and intelligence testing that was the first step. One thing that stood out in his memory was the tough IQ tests at NASA’s temporary headquarters at the Dolly Madison house. He was describing a periscope-like device he had tested on the F9F-8P Cougar when one of the interviewers told him a similar device was being planned for the Mercury capsule. Two other interviews were conducted by NASA psychologists and Carpenter became convinced that he could have done something absolutely childish and not gotten a reaction. Fortunately for him, he didn’t.

Satisfied that he had given it his best shot, Carpenter returned to the Hornet to wait, and that’s when the drama began. The news that he had made it to the next stage of the selection process arrived by U.S. mail – to his house! Rene Carpenter opened the envelope and read: “You have been chosen to proceed with further interviews and tests in connection with Project Mercury.” The letter included a phone number he had to call by Monday morning, and it was already Tuesday! Rene quickly dialed the number and told the man on the other end, “We volunteer!”

Rene must have made sure Carpenter got his orders. He would need them. Hornet’s skipper, Captain White, had a training cruise coming up and was not going to let his air intelligence officer off the ship, orders or not. So Carpenter did the only thing he could do. He called their contact person, Doctor Allen Gamble, at his house. Gamble called Chief of Navy Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke, who then called Captain White and stung his ears with some of the saltiest language to ever come out of the mouth of a Navy officer. Carpenter got his way, and the Hornet left on the training cruise without him.

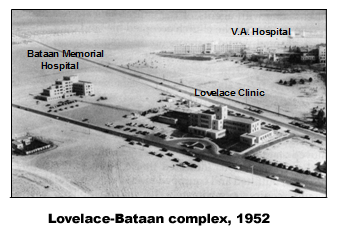

He reported to Lovelace Clinic and then Wright-Patterson for the infamous physical and psychological testing. Doctors poked and prodded at parts the candidates didn’t know they had. Ice-cold water was sprayed in their ears until their eyes spun. And these were all top military pilots. They hated doctors, who could find medical reasons why they couldn’t fly. One candidate lost his temper and stomped out. Carpenter took it in stride and his childhood in the high altitudes of Colorado helped him break records.

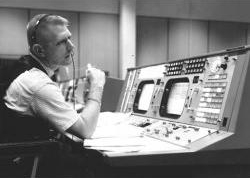

Bob Solliday remembered, “He had us all psyched out.” It quickly became obvious that the doctors were testing the candidates’ tolerance to stress as much as they were testing their bodies. The one who stomped out had obviously lost. While Carpenter pedalled on the bike, the doctors tested his ability to process oxygen by capturing the carbon dioxide he exhaled in bags. They ran out of bags. He blew into a manometer, a U-shaped device containing mercury similar to the one pictured at right, to test his ability to hold his breath. The previous record for this test was ninety seconds. Carpenter lasted three minutes.

Scott Carpenter’s association with the Lovelace Clinic wasn’t all tests. Doctor Lovelace invited him and a few other candidates over for dinner and, while they chatted, the subject of skiing came up. Carpenter asked about the condition of the local slopes and Lovelace said he would have to ask Doctor Ulrich Luft. Doctor Luft was one of several Germans who had come to America after World War II as part of Operation Paperclip, and he had a wide assortment of winter gear, some of it bearing the unmistakable insignia of the Nazis. Carpenter wisely did not ask many questions and chose the most inoffensive of the gear.

He went on to Wright-Patterson, where he met some of the more interesting psychological tests. He had to project a likely scenario onto a series of pictures. The “Panic Box” was a random collection of indicators, buzzers, lights and controls that the candidates had to operate to test their reflexes. Carpenter compared watching one man work it to watching a man go into convulsions. He broke a record on that one, too. When they put him in a blackout chamber, he contemplated a favorite physics problem, the expanding universe.

He celebrated the end of the testing at a Mexican restaurant with several other candidates and returned to the Hornet to wait. Rene Carpenter relayed word to him that he had been selected and he sprinted to Captain White. Of course, the Hornet was due to leave port that day. White’s reaction was not good and Carpenter again had to get an assist from Admiral Burke. Burke promised White that he would receive another Air Intelligence Officer but the country needed Lieutenant Carpenter. While Carpenter was collecting his gear, Captain White couldn’t resist asking him what the big deal was, anyway.

Carpenter answered, “I am going to ride the nose cone of a rocket around the world three times!”

White came close to making an anatomically impossible suggestion. It was the last time Carpenter saw the Hornet.

The Press Conference

April 9, 1959

Training for Mercury

From there, it was just a short step to the world of astronaut training. Nobody knew what to expect of mankind’s ability to live and perform in outer space. Some gloomy doctors anticipated a painful death waiting for them above the atmosphere. Some reporters may have gotten wind of this and frequently asked their families, “Aren’t you afraid he’ll be killed?” So they planned on making the training as tough as possible to make certain the astronauts were ready for anything outer space could throw at them.

From there, it was just a short step to the world of astronaut training. Nobody knew what to expect of mankind’s ability to live and perform in outer space. Some gloomy doctors anticipated a painful death waiting for them above the atmosphere. Some reporters may have gotten wind of this and frequently asked their families, “Aren’t you afraid he’ll be killed?” So they planned on making the training as tough as possible to make certain the astronauts were ready for anything outer space could throw at them.

The training process may have seemed like they were just making it up as they went along. The centrifuge was already in use and they added a device called the MASTIF, which would spin a man on all three axes as he tried to bring it under control. The idea was to simulate a spacecraft tumbling out of control and the MASTIF was best known for making astronauts dizzy. Later, someone realized that a malfunctioning spacecraft might also land astronauts in a place where rescuers couldn’t get to them immediately and added survival training. Classroom training was always part of it and they flew from place to place to learn about rockets, astronomy, and the Mercury capsule that was still being designed.

NASA wanted the astronauts involved with design from the start. Each of them were experienced test pilots who, in an emergency, might have to take control of the capsule and they took full advantage of their ability to give their input. To make the work easier, they divided it up into areas of specialization and Carpenter took on navigation and communications. They would meet in private to decide what recommendations they would make as a team. One thing they all agreed on was the need for a window so they could look out and orient themselves if instrumentation failed. Early designs for the Mercury spacecraft only allowed for a periscope and, while engineers did see their point, a window meant extra weight and they wouldn’t solve that problem until after Alan Shepard’s flight.

Training and visiting all of the contractors took them all over the country. At first, they took commercial air but got so fed up with having no planes of their own that one of them griped to a U.S. Senator. This caused some ruffled feathers over at NASA and they got some T-33 and then T-38 jets for their astronauts, which got them back in the cockpit and saved them time. It would also take a toll on astronaut families as many astronauts were only home on weekends and sometimes not even then.

For all their hard work, they found time for relaxation. They discovered a comedian named Bill Dana, who had built a career around his cowardly daredevil, Jose Jimenez. Jose Jimenez wanted to be an astronaut, but was too timid to get in his spacecraft. Pastimes like handball and skiing were favorites and some of the astronauts raised the practical joke to an art form.

Every single one of them hoped to be the first man in space. Finally, Bob Gilruth called them together to announce his decision. Alan Shepard would be first, Gus Grissom would be second and John Glenn would be backup for both. Scott Carpenter would eventually get his flight. But it would hinge on another man’s disappointment.

The Mercury Flights

Alan Shepard had a successful first flight in the Freedom 7, though there were some feelings floating around that he had been cheated out of his chance to be the first human in outer space. Some more cautious heads at NASA had insisted on a second chimp flight after the first chimp’s space capsule malfunctioned and landed far off course. In the meantime, the Russians put their first cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, into space just weeks before Shepard flew.

Alan Shepard had a successful first flight in the Freedom 7, though there were some feelings floating around that he had been cheated out of his chance to be the first human in outer space. Some more cautious heads at NASA had insisted on a second chimp flight after the first chimp’s space capsule malfunctioned and landed far off course. In the meantime, the Russians put their first cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, into space just weeks before Shepard flew.

Gus Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7 was basically a repeat of Alan Shepard’s flight, though his capsule sank.

Scott Carpenter became John Glenn’s backup for the first orbital flight, Friendship 7. John Glenn trusted Carpenter to attend the meetings and make the decisions he didn’t have time to make while he concentrated on training. They both spent a lot of time in the simulators, covering every imaginable variation of the flight. Glenn made a successful orbital flight, though a false reading that indicated a malfunctioning heat shield gave everybody a scare.

Deke Slayton was selected for the second orbital with Wally Schirra as his backup. Everything seemed to be going smoothly, and then one of the NASA doctors discovered an irregular heartbeat in Slayton during a run in the centrifuge. Slayton considered it to be minor but the condition was enough to get him yanked from the flight. Every single one of the astronauts considered that an overreaction. Wally Schirra expected to take his place but was informed that Carpenter had more simulation time and would take the flight instead. Carpenter felt terrible for Slayton, who would soon become the head of the Astronaut Office. It must have felt like a consolation prize but there was nothing to be done about it. Carpenter stepped up to the plate and named the Mercury spacecraft the Aurora 7.

Aurora 7

Preparations for Aurora 7

During the weeks leading up to the flight, Scott Carpenter spent as much time training and preparing as he could. He wished there were more hours in the day to make sure everything was ready to go, including himself. Like many pilots, he wasn’t so much afraid of dying as he was of messing up and leaving his four children without a father. The situation was made especially tense by the fact that certain members of the flight control team questioned his competence after a few training runs in which he appeared to be confused.

During the weeks leading up to the flight, Scott Carpenter spent as much time training and preparing as he could. He wished there were more hours in the day to make sure everything was ready to go, including himself. Like many pilots, he wasn’t so much afraid of dying as he was of messing up and leaving his four children without a father. The situation was made especially tense by the fact that certain members of the flight control team questioned his competence after a few training runs in which he appeared to be confused.

When he wasn’t working, he typically spent time either alone or with a few close friends. He was an amateur guitar player and would sometimes strum along while John Glenn sang. When the flight of Aurora 7 was delayed, he simply saw it as extra time to get ready.

His wife, Rene, was probably more nervous than he was. She came to Cape Canaveral with their children for the flight and got so caught up in the excitement that she didn’t have much appetite. She had teased Annie Glenn for losing weight before Glenn’s flight but, now, she knew the feeling. Otherwise, things stayed pretty normal for the Carpenter family, right down to phone calls from Scott Carpenter.

One mystery Scott Carpenter hoped to solve on the flight was the matter of Glenn’s “fireflies.” He had reported seeing little, glittering specks during the Friendship 7 flight, leading one of the men on the debriefing committee to joke, “What did they say, John?” Nobody knew what they were. Other objectives including photographing land features and weather patterns from orbit, testing atmospheric drag and color visibility by deploying an inflatable balloon, and observing liquid behavior in orbit.

By May 24th, 1962, everything was ready to go. Early starts were becoming an astronaut tradition on launch day and Scott Carpenter was already in the spacecraft by the time his wife woke in the beach house at 5:15 am.

Flight of Aurora 7

The countdown for launch went mostly as planned, except for one 45-minute hold at T-11 minutes to check on the weather. Scott Carpenter took the opportunity to call his family. The TV at the beach house they had rented was tuned to the live coverage and they planned to run outside to watch when the engines lit. He hadn’t planned on calling, feeling that he didn’t need the distraction, but decided at the last minute that he could handle it. His wife and kids were just eating breakfast when Wally Schirra put the call through and he did get a little teary-eyed while talking to them. Once they hung up, he returned to the business at hand.

The launch came off much smoother than Carpenter had imagined, with not as much vibration as Alan Shepard had experienced on his flight. Carpenter was aware mostly of the roaring of the engines and a swaying motion. As he climbed past 90,000 feet, he thought only, “What an odd place to be, and going straight up!” When he reached orbit, he noticed a peculiar sensation of floating and his report to Houston was a spontaneous exclamation: “I am weightless, and beginning the turnaround!” His spacecraft was rotating so he would travel backwards, with the blunt end of his capsule pointed toward the flight path.

Almost right away, he noticed that the automatic control system wasn’t working as well as it should have. He had to adjust his attitude manually to make observations on the ground and used up more fuel than he planned on. He would regret that later. His first sunset in space was a dazzling display of colors in strips ranging from yellow-gold to a deep purplish-blue that blended gradually with the black of space. He tested his ability to navigate by the stars and found that he could keep the capsule’s attitude aligned to one particular star.

Almost right away, he noticed that the automatic control system wasn’t working as well as it should have. He had to adjust his attitude manually to make observations on the ground and used up more fuel than he planned on. He would regret that later. His first sunset in space was a dazzling display of colors in strips ranging from yellow-gold to a deep purplish-blue that blended gradually with the black of space. He tested his ability to navigate by the stars and found that he could keep the capsule’s attitude aligned to one particular star.

When sunrise arrived, he got his first glimpse of the “fireflies.” They looked a lot like glittering snowflakes that got as big as half an inch across. He bumped his head against the capsule wall and saw more of them. “They are capsule emanating,” he told Houston. They were only flecks of water that had frozen on the exterior of the spacecraft and fallen off to float all around him.

The balloon experiment was only a partial success. It deployed but failed to inflate. Carpenter found it difficult to make any drag measurements and it moved randomly. He finally gave it up and tried to release it, without success. It continued to trail after him for the duration of the flight.

When his fuel became appallingly low, he gave up trying to control his attitude and just let the capsule drift with minor adjustments so he could make observations. His pressure suit was becoming overheated. His body temperature got as high as 102 degrees and he was beginning to have trouble expressing his thoughts to Houston. Some people in Mission Control feared that he might be delirious. He had to get himself cooled off and tried adjusting a dial on his suit. This worked best with the visor on his helmet closed.

His last orbit seemed to pass quickly. He took photographs, tracked stars, ate some miniature candy bars, and then had to adjust his attitude for re-entry. The automated control system was still malfunctioning, so he took manual control. He switched to fly-by-wire, which would let him use the fuel supply from the automatic system, but forgot to turn off the normal manual system. This meant more wasted fuel. When the rockets that would begin the reentry process failed to fire automatically, he pushed the button himself a second after the flight plan called for. The rockets fired two seconds afterwards. Because of those three seconds, he would land at least fifteen miles past the planned recovery area.

The reentry went smoothly at first. Carpenter was out of fuel in the manual tank and had only 15% left in the automatic tanks. He maneuvered as delicately as possible and began to roll the capsule at ten degrees per second when the capsule began falling through the atmosphere. The friction of reentry caused the temperature outside the capsule to soar to three thousand degrees but Carpenter never noticed the heat pulse he had been expecting. He saw a ring of fiery particles stretching out from the heat shield that he thought looked like a doughnut and a green, hazy glow around the narrow end. He spoke into the recorder, “I see a green glow from the small end. It looks almost as if it was burning away. Oh, I hope not.” He laughed at himself for that last line. It was straight out of Bill Dana’s cowardly astronaut act.

The capsule began swaying at an altitude of about 100,000 feet and Carpenter had to work to keep this under control. It burned through his remaining fuel and Carpenter considered the possibility that the capsule might tumble out of control. It would have justified the dizziness-inducing MASTIF and there was the possibility that such a tumble would cause the parachute to become tangled or damaged. Carpenter had to deploy a drogue chute 5,000 feet sooner than planned to stop it. When the main chute failed to deploy as planned, he triggered that manually, as well.

He picked up a transmission from Gus Grissom telling him that he was probably going to land outside the planned recovery area and there would be a delay picking him up. He tried to reply but couldn’t. He was out of range. He landed safely but no one knew where he was. Radar picked up nothing. He found out later that one man in Mission Control commented softly, “We may have lost an astronaut.” His family was clustered around their television, waiting tensely with the rest of the nation for news, either good or bad. Scotty Junior kept trying to cheer his mother up with jokes. Rene hoped he was all right, perhaps dazed or semi-conscious but alive.

In the meantime, he activated a homing device and decided to wait it out in his life raft. A friendly fish swam up and rested beside him. Carpenter was grateful for the company as he contemplated his recent adventure. Almost an hour later, he saw the first plane: appropriately enough, one of the P2V bombers he used to fly. Divers were in the water soon afterwards and one of them attached a flotation device to the capsule. Carpenter felt an irrational resentment for their presence but wanted to be friendly. He offered them some candy bars from his supplies and they politely refused. He was soon aboard the aircraft carrier Intrepid. His family cheered when they heard that they had recovered “a gentleman named Carpenter.”

In the meantime, he activated a homing device and decided to wait it out in his life raft. A friendly fish swam up and rested beside him. Carpenter was grateful for the company as he contemplated his recent adventure. Almost an hour later, he saw the first plane: appropriately enough, one of the P2V bombers he used to fly. Divers were in the water soon afterwards and one of them attached a flotation device to the capsule. Carpenter felt an irrational resentment for their presence but wanted to be friendly. He offered them some candy bars from his supplies and they politely refused. He was soon aboard the aircraft carrier Intrepid. His family cheered when they heard that they had recovered “a gentleman named Carpenter.”

In a classic joke, the University of Colorado decided that his problems with the pressure suit counted as field work in thermodynamics and awarded him a degree in engineering.

Story of Sealab II

Sealab II

Some fellows at NASA assumed that Aurora 7 had landed so far off course because Scott Carpenter messed up. According to some accounts, he had also made a comment during recovery that implied that some people in Mission Control weren’t doing their jobs, which further soured their relationship. Carpenter felt that he did the best he could, given that the automated system failed and cost him fuel, and he had a lot of activities to pack into three orbits. The culprit ultimately turned out to be a malfunctioning pitch horizon scanner.

Some fellows at NASA assumed that Aurora 7 had landed so far off course because Scott Carpenter messed up. According to some accounts, he had also made a comment during recovery that implied that some people in Mission Control weren’t doing their jobs, which further soured their relationship. Carpenter felt that he did the best he could, given that the automated system failed and cost him fuel, and he had a lot of activities to pack into three orbits. The culprit ultimately turned out to be a malfunctioning pitch horizon scanner.

In any case, he remained interested in underwater work. When he heard about a Navy project called Sealab, he felt it would be a good idea to get away from NASA for a while and bring some NASA experience to the project. He volunteered and was assigned to Sealab II.

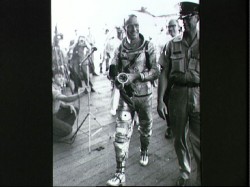

Sealab II had a few improvements over Sealab I: hot showers, refrigerators, and Tuffy the dolphin, who was trained to deliver supplies. Carpenter went down with the first team on August 28, 1965, and stayed 30 days. He was the equivalent of the Mission Commander on modern space shuttle flights and headed up two Sealab crews, each of which stayed in the Sealab facilities for fifteen days. The aquanauts tested new tools, salvage techniques and an electrically heated dry suit. They also conducted physiological experiments.

They had a telephone hook-up they could use to communicate with the surface and Carpenter got a chance to talk to Gordon Cooper and Pete Conrad while they were orbiting in Gemini 5. He joked that swimming around outside the Sealab capsule had to be easier than moving around outside the Gemini spacecraft. They also got a chance to talk with ocean pioneer Jacques Cousteau. The helium atmosphere inside the Sealab facilities made communication difficult.

They had a telephone hook-up they could use to communicate with the surface and Carpenter got a chance to talk to Gordon Cooper and Pete Conrad while they were orbiting in Gemini 5. He joked that swimming around outside the Sealab capsule had to be easier than moving around outside the Gemini spacecraft. They also got a chance to talk with ocean pioneer Jacques Cousteau. The helium atmosphere inside the Sealab facilities made communication difficult.

While helping with the return of the first crew to the surface and the descent of the second, Carpenter was stung by a scorpion fish. His arm swelled up painfully but he was able to bring it back to normal and also had the chance to test the effectiveness of drugs in a helium environment. They learned that the sense of smell diminishes in a helium atmosphere when nobody smelled burning toast, and helium will cool off a cup of coffee in seconds.

While helping with the return of the first crew to the surface and the descent of the second, Carpenter was stung by a scorpion fish. His arm swelled up painfully but he was able to bring it back to normal and also had the chance to test the effectiveness of drugs in a helium environment. They learned that the sense of smell diminishes in a helium atmosphere when nobody smelled burning toast, and helium will cool off a cup of coffee in seconds.

Cooking was an interesting experience. Griddle cakes did not cook through evenly. Because of their depth of slightly more than 200 feet, water boiled at 328 degrees Fahrenheit. Figuring out which burners were hot led to several burned fingers. Scientists were stumped when a cake that collapsed and was presumed ruined suddenly rose several hours later. (The aquanauts ate it, so there was nothing to test.) Whenever they wanted seafood, all they had to do was catch their own. Disclaimer: They did not eat Tuffy. No dolphins were harmed in the making of this page.

Cooking was an interesting experience. Griddle cakes did not cook through evenly. Because of their depth of slightly more than 200 feet, water boiled at 328 degrees Fahrenheit. Figuring out which burners were hot led to several burned fingers. Scientists were stumped when a cake that collapsed and was presumed ruined suddenly rose several hours later. (The aquanauts ate it, so there was nothing to test.) Whenever they wanted seafood, all they had to do was catch their own. Disclaimer: They did not eat Tuffy. No dolphins were harmed in the making of this page.

When Carpenter returned to the surface, he had to spend time in a decompression chamber, with one hilarious result. The President was going to make what should have been a straightforward call of congratulations but the decompression chamber had helium instead of hydrogen in it to prevent cases of the bends. Helium is a harmless gas but anyone who has inhaled helium balloons knows what effect it can have on the voice. Carpenter sounds like a cartoon character in the video below.

Scott Carpenter and the Helium Chamber

With LOLcats!

Post-NASA

After his Sealab experience, Scott Carpenter wanted to try for an Apollo flight but an attempt to repair the damage to his arm left him unable to fly. He left NASA and the Navy in 1967. He and Rene divorced soon afterwards; after a couple other failed marriages, he married his current wife in 1999. In the aftermath of The Right Stuff, he and the other Mercury astronauts found themselves back in the public eye. He thought of it as an entertaining tale that got most of the important information right but took literary license with some minor details. He remained active as a public speaker and advocate for issues regarding sea and space exploration and protecting the ocean’s ecology.

Scott Carpente passed away on October 10, 2013.

Scott Carpenter’s Official Website

Books By or About Scott Carpenter

Scott Carpenter Collectibles

[simple-rss feed=”http://rest.ebay.com/epn/v1/find/item.rss?keyword=Scott+Carpenter+astronaut&sortOrder=BestMatch&programid=1&campaignid=5337337555&toolid=10039&customid=Scott+Carpenter&listingType1=All&lgeo=1&descriptionSearch=true&feedType=rss” limit=5]