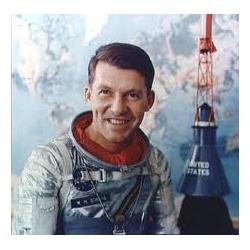

Wally Schirra

Early Life

Born to a World War One ace father and wing-walking mother on March 12, 1923, Wally Schirra would boast to any fellow pilot who tried to one-up him with their aviation experience that he was flying while still in the “hangar”. His childhood heroes included aviators like Clarence Chamberlin, Charles Lindbergh, and James Doolittle. He graduated from high school in 1940 but did not give much thought to the war going on in Europe. Instead, he pursued interests such as automobiles and swing music. Tinkering with a Plymouth he owned led to his first basic engineering lesson when he noticed that the engine was “loose,” moving in relation to the frame. His father explained that the engine mounts were made of rubber, producing what advertisers called “floating power.”

With his father’s support, he went to West Point, changing a letter on his application from USMA to USNA at the last minute. This meant he would go into the navy. Though it seemed like a last-minute decision, he admits in his autobiography to having considered the navy since seeing a sharp-looking fellow in navy uniform as a young child. He spent three whirlwind years in a acceleration course; one his few clear memories involved a midshipman who would steal and sell exams. Thanks to the skilled application of peer pressure, the midshipman only lasted a month.

After graduation, he visited his parents in Arlington, Virginia. He was a member of the local Army-Navy Country Club and went there for a swim. He noticed a pretty girl and asked around who she was, but no one knew. Finally, he got up the nerve to approach her and said, “Hi, I’m sorry, but no one seems to know you. I’m Wally Schirra.” Her name was Josephine “Jo” Fraser. He asked her to a dance that evening and she tentatively said yes. At the dance, she wanted to jitterbug, but her mother and stepfather were there. Her stepfather was Captain William T. Kenney and Schirra was an ensign, so he was too nervous about looking like a fool in front of a Navy Captain. But Captain Kenney went off jitterbugging with his wife and that was the last time Schirra ever refused to jitterbug with his future wife.

Brown-Shoe Navy

Wally Schirra went on to become become a member of the “Brown-Shoe Navy,” a Navy fighter pilot, as opposed to the “Black-Shoe,” or sea, Navy. But first, he had to put in a year at sea. He requested cruiser duty and was assigned to Alaska, an armored cruiser built to counter reports of a new Japanese vessel that later turned out to be false. Alaska was deployed anyway and arrived at Pearl Harbor in January 1945. Schirra didn’t join it until July 1945, while it was in Okinawa. The war ended the next month, so he only saw a hint of action when a kamikaze hit the nearby Pennsylvania.

Wally Schirra went on to become become a member of the “Brown-Shoe Navy,” a Navy fighter pilot, as opposed to the “Black-Shoe,” or sea, Navy. But first, he had to put in a year at sea. He requested cruiser duty and was assigned to Alaska, an armored cruiser built to counter reports of a new Japanese vessel that later turned out to be false. Alaska was deployed anyway and arrived at Pearl Harbor in January 1945. Schirra didn’t join it until July 1945, while it was in Okinawa. The war ended the next month, so he only saw a hint of action when a kamikaze hit the nearby Pennsylvania.

After the official end of the war, Alaska docked at Tsingtao during a show of force and Schirra went into town on liberty with two other ensigns. They rented saddle horses and rode out into the hills surrounding the city. Pretty soon, they came into view of what looked like a settlement but turned out to be a Japanese fort still on wartime alert. Thinking the three men were a patrol sent out to accept their surrender, the fort lowered its flag and the senior ensign accepted the sword of the Japanese commander. The sword was later presented to Alaska skipper Captain Kenneth Noble. Schirra also picked up a pistol as a souvenir and bought a motorcycle for fifty dollars. The motorcycle came back to America lashed to Alaska’s afterdeck. He later sold it because his wife couldn’t stand the noise.

Alaska returned to New York in December, 1945 and was mothballed a few months later. In the interim until Schirra’s next assignment, he married Jo Fraser and was soon assigned to Tsingtao to join the staff of Admiral Charles Maynard Cooke. His wife joined him soon afterward, also on assignment. He was a briefing officer, responsible for keeping the senior staff informed on subjects like the course of typhoons and their effect on the fleet. He learned a harsh lesson in trusting the native Chinese and their reading of the weather when he ignored some Buddhist monks’ warning of a typhoon that would hit Wangpoo Harbor in Shanghai. His radar indicated otherwise but the monks were proven correct. Eventually, the entire Tsingtao staff was forced to pull out when the Communists overran China.

He gained his wings in June of 1948. During his pilot’s training, he and Pinky Howard were at a window with a woman. Schirra apparently didn’t remember her name. Pinky Howard had just been promoted to Lieutenant junior grade. She told them she had one fighter billet and one seaplane billet and ordered them to draw straws. Howard tried to pull rank (Schirra was still just an ensign), but the woman told him what she thought of the difference between j.g.’s and ensigns and repeated her order. Schirra became a fighter pilot; Howard resigned a few years later. Schirra was assigned to Quonset Point, Rhode Island and was also promoted.

There, he was introduced to, among other planes, the F8F Bearcat. Like most fighter pilots, he was a hotshot. During one flight in the Bearcat, he was finishing up a practice gunnery run and coming in for a landing when he got caught in turbulence. His Bearcat flipped and he was flying upside down two feet off the runway. He managed to right his plane by hitting the throttle and pushing the stick forward and made a smooth landing. The skipper thought he had done that on purpose and chewed him out but Schirra could only kiss the ground. The incident was seared in his memory and he later found out that the skipper became a boxing referee after leaving the Navy.

When the Korean War started in 1950, Schirra signed up for an exchange program that landed him with an Air Force wing. He wound up having to train the entire wing to fly the F84 Thunderjet, and then they were assigned to Itazuke Air Force Base in Japan. It was strange to him at first. The last time he had been in Japan, they had been enemies. Now, they were allies. Within a month, they were reassigned to a base in South Korea. He made ninety combat flights in eight months and shot down two enemy planes.

He made it back to the U.S. and became a Navy test pilot. While working on a report for the Mach 1 plane called F4D, he spotted a bright light in the sky that he realized was Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite. He considered the inequity of working on a Mach 1 plane when Sputnik had to be making Mach 25. In February 1959, he received blind orders to report to Washington. There had been rumors that a team of astronauts might be selected but Schirra hadn’t thought anything of it. When he reported to the Pentagon, he learned that he was part of a group of thirty-odd candidates for a NASA program called Mercury, given the goal of sending a man into space.

Introduction of the Mercury 7

The Reluctant Astronaut

NASA was a new organization, designed from the start to be a civilian agency. Joining up as an astronaut meant that Schirra would have to suspend his career as part of the brown-shoe Navy, something he wasn’t thrilled about. Unable to find a graceful way out, he went through the intense psychological and physical testing along with all of his fellow prospective astronauts. Early on, one official reassured all of them, “Not to fear, we’ll send chimpanzees first.” Perhaps he didn’t realize that not all of the candidates were worried about the risk.

NASA was a new organization, designed from the start to be a civilian agency. Joining up as an astronaut meant that Schirra would have to suspend his career as part of the brown-shoe Navy, something he wasn’t thrilled about. Unable to find a graceful way out, he went through the intense psychological and physical testing along with all of his fellow prospective astronauts. Early on, one official reassured all of them, “Not to fear, we’ll send chimpanzees first.” Perhaps he didn’t realize that not all of the candidates were worried about the risk.

Finally, in March 1959, he was informed that he had made the final cut. Despite lingering misgivings, he accepted and was ultimately glad he did. In mid-April, NASA introduced Schirra and six other men to the world as the Mercury astronauts. They were all veteran test pilots and small-town boys, of whom only John Glenn had previously had a taste of fame after his record cross-country flight. Their first press conference startled them with a large crowd of reporters and it quickly became obvious that they needed an agent to manage their appearances. Tax lawyer Leo DeOrsey offered to take the job with no fee and negotiated a deal with Life Magazine that gave their reporters exclusive access to the astronauts’ personal stories.

Officially, the astronauts were placed on leave from their respective military branches and assigned to NASA. Schirra was promoted from lieutenant commander to commander during the Mercury program. They were discouraged from wearing their uniforms except at funerals or visits to Washington, which bothered Schirra, who was proud of being part of the Navy.

They began doing things as a team right away, including a group effort to quit smoking with mixed success. Gordon Cooper was the only non-smoker in the group and the pack-a-day Schirra reports becoming irritable to the point where Jo threatened to kick him out of the house. The astronauts were quite competitive, including fairly typical pilot egos, but trusted each other to check out equipment. They would also hold meetings when there was a specific subject to be addressed as a group. One such meeting involved windows on the Mercury spacecraft. They felt that a successful space rendezvous required being able to look out a window rather than strictly rely on their instruments. Their view won out.

Astronaut training was tough, as nobody really knew what to expect of mankind’s ability to live and work in space at the time. In retrospect, some of the early training tools were useful, but others were what Schirra called “merely instruments of torture.” As time and experience progressed, most of the “instruments of torture” dropped out of sight. One of those that were phased out was the MASTIF, meant to simulate a spacecraft out of control and spinning on all three axes. Schirra’s main objection to it was that it simulated a situation that was unlikely to happen in real life. As it turned out, Gemini Eight came closest to it when a malfunctioning thruster caused the crew to temporarily lose control and abort the mission early.

Astronaut training was tough, as nobody really knew what to expect of mankind’s ability to live and work in space at the time. In retrospect, some of the early training tools were useful, but others were what Schirra called “merely instruments of torture.” As time and experience progressed, most of the “instruments of torture” dropped out of sight. One of those that were phased out was the MASTIF, meant to simulate a spacecraft out of control and spinning on all three axes. Schirra’s main objection to it was that it simulated a situation that was unlikely to happen in real life. As it turned out, Gemini Eight came closest to it when a malfunctioning thruster caused the crew to temporarily lose control and abort the mission early.

Survival training was up there with training for spaceflight. NASA anticipated that an emergency landing might put them down in a remote location where immediate rescue wasn’t possible. Schirra recalled one incident involving a reporter named Ralph Morse, who cleverly discovered their survival camp in the Nevada desert and drove his Jeep out to meet them. Morse knew perfectly well that the survival training sessions were supposed to be off-limits to reporters, so naturally, Schirra and Alan Shepard just had to get revenge. They distracted Morse by letting him have a burger and a cookie in their tent, and then planted a smoke flare in his Jeep. Then, they told Morse, “Your Jeep is in the way. You’d better move it.” When Morse started his Jeep, the flare went off, covering him with green dust and ruining the vehicle. Morse took it like a good sport but got the message.

Gotcha!

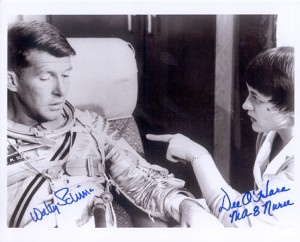

“Gotchas” were one way the astronauts could humorously relieve the occasional frustrations that went along with being part of the space program. Wally Schirra was one of the biggest jokers in the bunch and, while most of his pranks were on his fellow astronauts, other employees of NASA were not immune. One of his victims was a nurse named Dee O’Hara, whose duties included collecting urine samples from the astronauts. One day, Schirra and Gordon Cooper filled a five-gallon bottle with a mix of warm water, iodine, and laundry detergent, gave it a good shake to make it all foamy and placed it on her desk with a label and a few lollipops attached. Miss O’Hara reportedly took it quite well.

Neither was he above playing jokes on complete strangers. When staying at various hotels, a favorite was to parade through the hotel lobby with a bloodied bandage wrapped around his arm, claiming that he had been attacked by a mongoose. This provided a stream of people who had to see for themselves. The “mongoose” was actually a jack-in-the-box contraption disguised as a nondescript animal, designed to spring out when the lid was lifted.

Of course, others would “gotcha” Schirra right back. He kept up his interest in cars and, before his Gemini flight, Ray Firestone of Firestone Tire and Rubber told him, “Wally, if you pull off this rendezvous tomorrow, I’ll give you a new set of tires for your car.” Because Schirra had an Italian car, this meant they would be an expensive set of tires called Boranis. They planned on sending him the wheels, too. What Schirra didn’t know was that Firestone and race car driver Jim Rathmann planned to include a wheel that had been pounded into an oval shape, giving the car an inexplicable bounce. The gag wheel never arrived, but the wheels were screwed on backwards and wound themselves loose. He was driving past the Manned Spacecraft Center when one of them finally came off and his car slid to a stop. So the planned gotcha never happened, but he was the victim of an unplanned gotcha.

Flight of Mercury-Atlas 8 (Sigma 7)

Mercury-Atlas 8

When Schirra was assigned to Mercury 8, he pushed for six orbits, which would be the most to date, and also insisted on flying manually as opposed to “chimp,” or automatic, mode. NASA personnel were concerned about fuel after the flight of Scott Carpenter’s Aurora 7, in which the fuel tanks had been all but emptied due to malfunctions and possible human error. However, Schirra had a technique for cutting down on fuel usage in mind.

When Schirra was assigned to Mercury 8, he pushed for six orbits, which would be the most to date, and also insisted on flying manually as opposed to “chimp,” or automatic, mode. NASA personnel were concerned about fuel after the flight of Scott Carpenter’s Aurora 7, in which the fuel tanks had been all but emptied due to malfunctions and possible human error. However, Schirra had a technique for cutting down on fuel usage in mind.

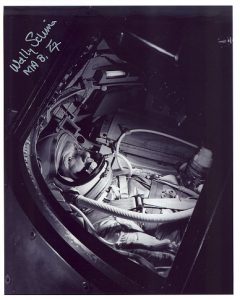

In those days, it was standard procedure for astronauts to name their spacecraft. Schirra named his the Sigma 7, the “7” in tribute to the original seven astronauts in the space program. He chose “Sigma” as a tribute to engineering excellence.

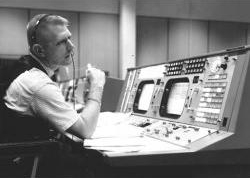

The launch occurred on October 3, 1962. He promptly disabled the automatic attitude control. His technique worked to conserve his fuel so carefully, adjusting the attitude with the minimum use of his thrusters, that he had more than half the fuel left at the end of his flight and had to dump it before reentry. In doing so, he proved the advantage of having a human instead of a computer in charge of the spacecraft and earned a rare on-the-record compliment from Flight Director Christopher Kraft, who called it a “true engineering flight”.

Gemini 7/6

Gemini VI

The original goals of Gemini VI included a planned rendezvous with an unmanned spacecraft named Agena. When the Agena craft failed, the objective changed to a rendezvous with Gemini VII. Gemini VII launched first, and then the launchpad crews quickly turned things around to prepare for the Gemini VI launch. The countdown reached zero, the engines fired, and then nothing happened. The crew could have aborted, a risky procedure that involved opening two hatches on top of the Gemini and sending two ejection seats through, but they sat tight. Wally Schirra said of it later, “I could tell by the seat of my pants that we hadn’t launched.”

The original goals of Gemini VI included a planned rendezvous with an unmanned spacecraft named Agena. When the Agena craft failed, the objective changed to a rendezvous with Gemini VII. Gemini VII launched first, and then the launchpad crews quickly turned things around to prepare for the Gemini VI launch. The countdown reached zero, the engines fired, and then nothing happened. The crew could have aborted, a risky procedure that involved opening two hatches on top of the Gemini and sending two ejection seats through, but they sat tight. Wally Schirra said of it later, “I could tell by the seat of my pants that we hadn’t launched.”

Gemini VI finally got off the ground on December 15. Because it was the Christmas season, Schirra’s fellow crewman, Thomas Stafford, reported an apparent UFO: a command module being towed by eight smaller modules, moving rapidly north to south and guided by a man in a red suit. Schirra also played “Jingle Bells” on a harmonica.

One phenomenon, known to the astronauts as “fireflies,” did cause some concern for Stafford. He looked out the window and saw what he thought were stars. Taking this to mean that they had overshot Gemini VII, he said, “Holy cow, Schirra! You blew it!” Schirra had to explain to him that they were only drops of frozen water from their own spacecraft.

Gemini VI maneuvered to within inches of Gemini VII, close enough for the two crews to get a good look at each other. Ever the joker, Wally Schirra held up a sign that said, “Beat Army.” Borman retorted, “Oh, Wally has a sign. It says, ‘Beat Navy’.”

The mission was a success and they splashed down on December 16th.

Launch of Apollo VII

Apollo VII

Apollo VII was Schirra’s longest space flight at 10 days, 20 hours and took on most of the goals that had been set for Apollo 1, in which three astronauts had died in a launchpad fire. Those goals included demonstrating Command/Service Module rendezvous capability, demonstrating crew/space vehicle and mission support facilities performance during a manned Command/Service Module mission, and demonstrating Command/Service Module (CSM) and crew performance.

Schirra insisted on having hot coffee during the mission. To make his point, he held a meeting and arranged a “gotcha” on NASA decision makers: he had snacks delivered but no coffee. He then dared them to go without coffee for just one day. They took the point.

The crew came down with the worst case of the cold ever recorded in space. They did make one unplanned contribution to medical science by discovering that having a cold in space is somewhat different from having a cold on Earth’s surface. For one thing, mucus doesn’t drain in zero G. As a result, the crew suffered from clogged up ears and noses. The only relief is to blow hard, risking damage to ear drums. While they later claimed that the colds were not as bad as they were made out to be, that certainly did nothing for their moods.

Schirra was also concerned about what re-entry under such conditions would do to their ears and refused to make the crew wear their helmets, though Deke Slayton tried to insist on it. They were grateful to the person who thought of stocking Kleenex and Actifed for them and used up nearly their entire supply. Schirra later went on to be a spokesperson for Actifed cold medicine, joking that he used to fly in a capsule and now he promoted them.

Wally Schirra also became uncharacteristically irritable during the flight. He vetoed a planned morning TV special on the grounds that they hadn’t performed morning checks yet. It got so bad that newspapers in Houston ran the headline, “Captain Awakes Grouchy”. Nobody ever found out why Schirra suddenly went from the class clown of the Mercury astronauts to somebody who could compete with Oscar the Grouch. He became so argumentative that, toward the end of the flight, Flight Director Gerry Griffin was heard to say, “I have finally had it with this crew.”

Apollo VII accomplished its objectives with flying colors and splashed down on October 22, 1968.

Legend of the Turtle

The true Turtle is a fun-loving, clean-thinking, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed individual who realizes that one never gets anywhere in life unless one sticks one’s neck out. “Turtles” are often leaders in government, finance, entertainment, aerospace and all other areas where aggressiveness, a feeling for fair play, clean thoughts and a sense of humor are keys to success. The Turtle Club was started by a group of WWII pilots; membership requires adherence to the Turtle Creed and always giving the p@$$word (slight warning for later) when asked for.

The true Turtle is a fun-loving, clean-thinking, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed individual who realizes that one never gets anywhere in life unless one sticks one’s neck out. “Turtles” are often leaders in government, finance, entertainment, aerospace and all other areas where aggressiveness, a feeling for fair play, clean thoughts and a sense of humor are keys to success. The Turtle Club was started by a group of WWII pilots; membership requires adherence to the Turtle Creed and always giving the p@$$word (slight warning for later) when asked for.

According to legend, the first Turtle was a man who was pure of thought and noble in character. Unfortunately, all of his neighbors were vulgar and generally uncouth, to put it politely. Bemoaning his fate, never to share his purity with another Turtle, he retreated like a turtle into his shell. Finally, he resolved to search for others like him. His search often took him into bars and saloons, generally not places where one might expect to find Turtles, but one cannot always be picky. Inevitably, his money ran out and his only remaining possession was a good-natured and loving donkey he had raised himself.

One day, he received a tip on a horse running at long odds in a race. Though generally not a betting man, he was resolved to find a way to continue his search and he reluctantly put his donkey up as a bet. He won and was able to continue his search for many years. This gave rise to the Turtle Password: one Turtle will ask, “Are you a Turtle?” And the other would have to promptly answer: “You bet your sweet ass I am!” or buy the first person a beer.

Two of Wally Schirra’s favorite astronaut-related moments had to do with Turtles. The first came when he was only three minutes into his Mercury flight. Deke Slayton came on the radio and asked, “Hey, Wally, are you a turtle?” Not wanting to embarrass himself in front of every American listening to the live broadcast, he switched his microphone from live radio to the recorder and responded, “You bet your sweet ass I am!” Later, while on the recovery ship Kearsarge, he was asked about his answer and played back the recording.

In May of 1963, he was at the White House and John F. Kennedy asked him, “By the way, Wally, are you a turtle?” Schirra had to think twice before giving the proper response to the President’s face!

Learn more about Wally Schirra at the Official Wally Schirra Web Site or with these books.

Wally Schirra Collectibles

[simple-rss feed=”http://rest.ebay.com/epn/v1/find/item.rss?keyword=Wally+Schirra+Astronaut+-sunglasses&sortOrder=BestMatch&programid=1&campaignid=5337337555&toolid=10039&customid=Wally+Schirra&listingType1=All&lgeo=1&descriptionSearch=true&feedType=rss” limit=5]