Expedition 4

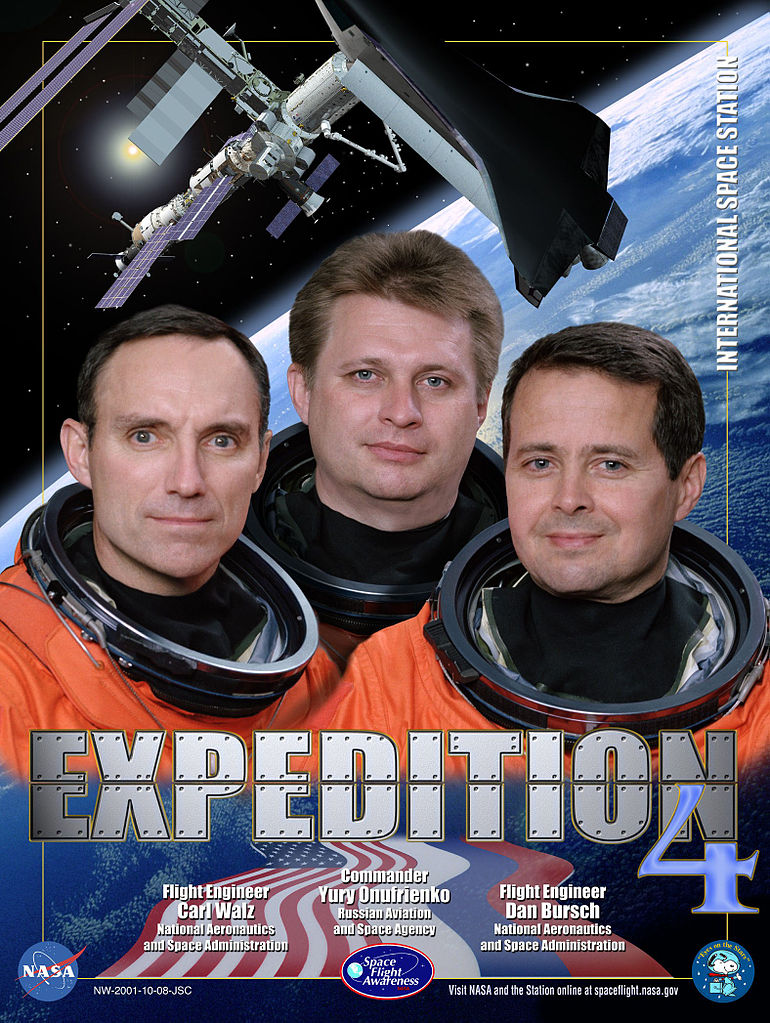

With the Endeavour’s departure, the Expedition 4 crew began to settle in. Yuri Onufrienko had previously served on Mir and Daniel Bursch commented that his experience was a good help while they settled in for the long haul. They got cargo stowed from the Endeavour and Progress-M1 7, activated experiments and kept an eye on equipment. Despite the new thermal blankets, the gimbal system did stall up. They were able to reboot it and the ground troops in Houston monitored it to make sure it continued to run smoothly.

With the Endeavour’s departure, the Expedition 4 crew began to settle in. Yuri Onufrienko had previously served on Mir and Daniel Bursch commented that his experience was a good help while they settled in for the long haul. They got cargo stowed from the Endeavour and Progress-M1 7, activated experiments and kept an eye on equipment. Despite the new thermal blankets, the gimbal system did stall up. They were able to reboot it and the ground troops in Houston monitored it to make sure it continued to run smoothly.

The holidays were days to relax. On Christmas and New Year’s Day, they took time off to talk to their families. Then, it was back to their experiments. Medical experiments included the H-Reflex experiment previously carried out by Expedition 3, and also the Pulmonary Function Facility experiment which studied lung function in microgravity. Walz and Burch operated the Canadarm2, moving it to a different location on the space station while Houston measured its effects on the station’s exterior. Walz often felt like a lab technician in the world’s most expensive laboratory, tending experiments and reporting the results to scientists on the ground.

On January 14th, 2002, Yuri Orufrienko and Carl Walz went out on an EVA to move the Strela-2 crane on Pirs from the Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA) to the Docking Compartment. Using the Strela-1 crane to move around, they began their spacewalk at 15:59 and finished up 6 hours and 3 minutes later. The two cranes could now work in tandem to assist future EVAs and construction of the International Space Station.

On January 14th, 2002, Yuri Orufrienko and Carl Walz went out on an EVA to move the Strela-2 crane on Pirs from the Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA) to the Docking Compartment. Using the Strela-1 crane to move around, they began their spacewalk at 15:59 and finished up 6 hours and 3 minutes later. The two cranes could now work in tandem to assist future EVAs and construction of the International Space Station.

A second EVA by Orufrienko and Daniel Bursch on January 25 installed deflectors behind Zvezda’s maneuvering thrusters, retrieved the Kroma-1-0 experiment designed to capture samples of thruster effluent, and installed a second ham radio antenna. They also mounted the Plantan-M experiment, which would measure neutral low-energy nuclei coming from the sun and from outside the solar system, and two material exposure experiments. For their final task, they installed fairleads on Zvezda’s exterior handrails. This would hopefully keep safety tethers from EVA suits from getting tangled up on equipment.

As January wound down, the Expedition 4 crew enjoyed a quiet week while they took care of routine maintenance. They replaced a hard drive on one of the ever-touchy Command and Control computers, handled some troubleshooting to track down an echo in the communications system, installed a new laptop in the QUEST airlock module and prepared the KURS rendezvous equipment on Progress-MI 7 for return to Earth. Experiments also continued as they downloaded the results of a study of the crew’s exposure to radiation and the Renal Stone Experiment meant to study astronauts’ susceptibility to kidney stones in space.

The crash of Zvezda’s main computer on February 4 threatened the station’s attitude control and several sensitive experiments that might not survive without power. While astronauts powered down equipment in case the solar panels couldn’t provide enough electricity, controllers in Houston and Korolev worked to reboot the computer. Within 6 hours, everything was back to normal. It didn’t last long. A couple of days later, the Remote Power Conversion Module (RPCM) went down, threatening the electrical system’s ability to distribute power throughout the station. Repairs took a few days and required the removal of Bursch’s sleeping compartment. The crew took the opportunity to place a few extra high-density radation protection bricks behind the compartment.

On February 15, the Intravehicular Officer on the US side got his first workout in Houston’s control center. This would be the first time Astronaut Joe Tanner would be in charge of directing an EVA from the ground rather than in orbit. The two Americans, Walz and Bursch, began “US EVA 1” at 0638, wearing American EMUs and making their egress from the American Quest module. The EVA plan included connecting some cables near the base of the Z-1 Truss, but this was cancelled when the circuit caused unexpected power readouts. Walz removed four thermal blankets from the Z-1 Truss and sent them inside for storage, while Bursch sent tools that the STS-110 crew would use during planned EVA activity and sent them into the Quest airlock. The two spacewalkers tightened up locks on Quest that were a little loose and removed two adapters that had been holding the Strela cranes in place. An inspection of the Materials on International Space Station Experiment (MISSE) revealed that some of the samples had begun to peel off their mounts. The external cable connectors looked fine. The spacewalkers finished their spacewalk at 1225.

That day, the station crew stayed up past their bedtimes to track down a bad odor caused by equipment used to clean the EMU suits. It was finally decided to power off the equipment and seal Quest to keep the odor from spreading for the time being. As February wound down and March got into full swing, the crew got to play with some small toys. As part of an educational package, they used those toys to demonstrate basic physics in a microgravity environment. They also moved Canadarm2 and got EarthKAM ready for some students to take some pictures of Earth by remote control. In the process, an avionics system and a secondary computer on Canadarm2 failed.

While Houston went into troubleshooting mode on Canadarm2, the crew did an inventory of items on the ISS, loaded up Progress-MI 7 with trash, and prepared for the arrival of Progress-MI 8. When Progress-MI 8 arrived on March 24, cargo included fresh fruit and care packages from family members and Bursch expressed his appreciation in an email, commenting that he felt like a kid at Christmas as the crew unpacked the items.

On the ground, space agencies worldwide were facing the usual challenges. The European Space Agency announced that it would devote 1/3 of its ISS space for experiments to commercial applications. The American Aerospace Safety Advisory Board warned that NASA was taking too narrow a focus regarding the Space Shuttle and was flirting with disaster. The Shuttle was now losing foam with every flight and facing other technical difficulties and NASA would find out the truth behind this warning the hard way. Critics also challenged NASA’s estimation of costs and record-keeping related to where their money was going. Its primary contractor, Boeing, was also facing criticism for not including the costs of certain items in its price estimates. While officials tried to insure the public that the space station was still on track financially, NASA Space Station manager Thomas Holloway stated that the International Space Station could still reach the “Core Complete” goal by 2006.

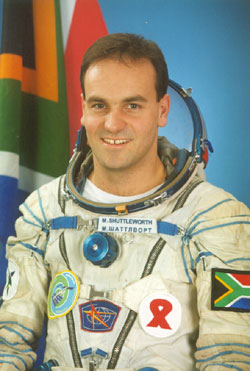

Soyuz TM-34

Soon after the undocking of STS-110, Expedition 4 was preparing for the arrival of a new Soyuz that would become their new ride home in case they needed to evacuate. Soyuz TM-34 included Expedition 1’s Yuri Gidzenko as the Soyuz commander, Flight Engineer Roberto Vittori from Italy, and another “space tourist,” Spaceflight Participant Mark Shuttleworth from South Africa. South African President Thabo Mbeki expressed his pride in Shuttleworth’s trip to space in a phone call: “It’s a proud Freedom Day because of what you’ve done.” Shuttleworth admitted to a bit of nervousness during the launch and acknowledged the possibility that a space tourist could damage delicate equipment: “Although it’s very, very large, we have to move very carefully. As you can see around us, there are tons of very precious and very sophisticated equipment. We hope that we wil be good guests.” By this point, the international partners had come to terms with the possibility of having paying visitors to the space station and had established a set of rules. Paying space flight participants would be the responsibility of the Soyuz commander and wouldn’t need an escort into the American modules; he could use a laptop to send emails and work on a few of his own experiments; and Shuttleworth was the first space tourist to receive training in Houston. In an interview, Shuttleworth’s predecessor, Tito, expressed his delight that the international space community had begun to accept the idea of private citizens paying to go into space.

The Russian “space tourist” program, combined with an American reluctance to invest any more cash in the Russian part of the space station, helped to force the issue of Russian commitment to the International Space Station. It was obvious that the revenues from Russian-based space tourism could be pumped into the Russian space agency. If they were unwilling to do so, they would be forced to withdraw and end their space program for the foreseeable future.

With the departure of Soyuz TM-33, the crew was again free to focus on experiments and preparations to return home. Onufrienko made repairs to a malfunctioning oxygen generator while Russian officials assured the public that the crew had enough backup oxygen generators to last a few months in the event of an irreparable failure. The original plan was for STS-111 to launch at the end of May. Repeated scrubs pushed it back to June 5. After six months in space, the Expedition 4 crew was eager to come home.

Six Months on the Space Station

Have you ever wondered what it’s like to live in a small space with two other people for six months? Astronauts have admitted that they looked forward to Space Shuttle visits just so they could see other faces. Here’s Expedition 4 Flight Engineer Dan Bursch’s take on what it’s like to live on the International Space Station for six months.

International Space Station Collectibles on eBay

[simple-rss feed=”http://rest.ebay.com/epn/v1/find/item.rss?keyword=International+Space+Station&categoryId1=1&sortOrder=BestMatch&programid=1&campaignid=5337337555&toolid=10039&listingType1=All&lgeo=1&feedType=rss” limit=5]