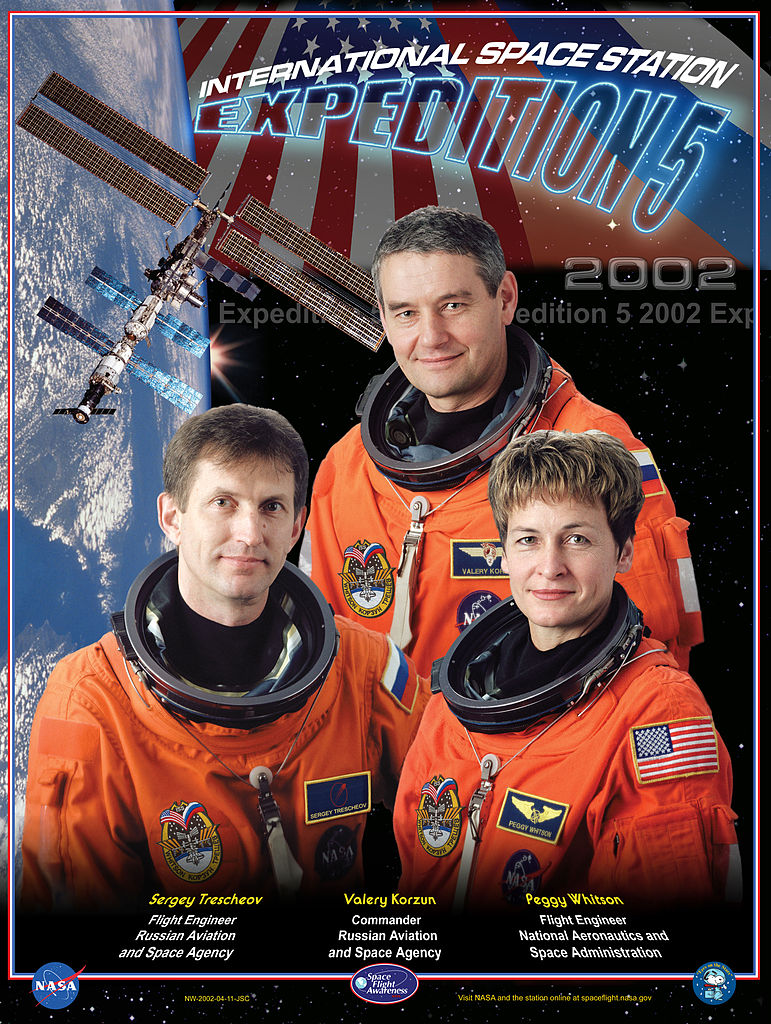

Expedition 5

As Expedition 5 settled in, the crew took more pictures of wildfires in Arizona and Colorado and activated new experiments that included a study of liver cell development in microgravity. Maintenance tasks included replacing a hard drive for the Zeolite Crystal Growth experiment in EXPRESS Rack 2. They also filled another Progress with rubbish and it burned up in the atmosphere on June 25. On the ground, Houston grounded its fleet of shuttles due to cracks in metal liners used to direct liquid hydrogen flow. The Expedition 5 crew received the news that their stay was likely to be extended while the shuttles were down for maintenance.

Progress M-46 arrived on June 29 and the Expedition 5 crew unloaded and logged the contents. Whitson made some repairs to the Medium Rate Communications Outage Recorder (MCOR), which had been down for three weeks. She also rehearsed maneuvers with Canadarm2 in preparation for the arrival of the S-1 ITS segment. These tests included moving Canadarm2 off of Destiny for the first time by attaching the free end to a fixture on the S-0 truss segment. She worked with Korzun to replace a malfunctioning Disiccant/Sorbent Bed Assembly in the Carbon Dioxide Removal Assembly (CDRA).

Scientific work also continued with experiments that were rapidly becoming station mainstays: the PuFF experiments to measure the lung functions of the crew, the ADVASC which now featured soybean plants, and the Renal Stone Experiment. The Renal Stone Experiment was especially important to the astronauts because, as Whitson explained, people in space ran the risk of developing kidney stones during a mission, which could be painful enough to incapacitate an astronaut and force an aborted mission. They were using a drug to attempt to inhibit stone formation.

As August began, so did Expedition 5’s preparations for the two Stage EVAs planned for August 16 and August 26. Valeri Korzon and Peggy Whitson moved Canadarm2 to a position where it could film the Payload/Orbital Replacement Unit Accommodations (POA) going through the motions of grasping a payload. During the POA’s operations, a computer put the POA into “Safe Mode” when it detected that the motor was moving too fast. The POA was rebooted and then operated at a slower pace and the second try was successful. Then, Canadarm2 was repositioned so that its cameras could capture video of the Stage EVA.

The Spacewalks of Expedition 5

On August 16, Peggy Whitson and Valeri Korzun used one of the Strela cranes on the Pirs docking module to move six micrometeroid shields from PMA-1 to their permanent locations around Zvezda and secured them into place. Planned activities had also included refurbishing an experiment designed to capture Zvezda’s thruster “exhaust” and take samples of residue on Zvezda’s exterior, but this was abandoned due to the late start of the EVA. This shortened the EVA from Korzun’s original estimate of six hours to 4 hours and 25 minutes.

The EVA on August 26 featured Korzun and Sergei Treschev. They installed a framework on Zarya for stowing equipment on future spacewalks, holders to train umbilicals used on spacesuits and prevent them from becoming tangled, and exchange trays of samples used in a Japanese material exposure experiment. They also took care of the tasks that had been abandoned on the first EVA.

Peggy Whitson: First ISS Science Officer

Peggy Whitson was keeping busy with her science experiments. She cleaned the Microgravity Science Glovebox used to contain experiments with materials that could be hazardous if they escaped and prepped it for the Pore Formation and Mobility Investigation, a study of how bubbles formed and moved in fluids. She replaced a smoke detector on the EXPRESS-2 rack. On September 11, 2002, she removed the final sample of the SUBSA experiment meant to study a hypothetical new method for producing semiconducting crystals.

NASA administrator Sean O’Keefe addressed the crew directly on September 15. He designated Peggy Whitson as the first ISS Science Officer and announced plans to increase the scientific payload on the International Space Station. Though Expedition 5 was her first space mission, she was rapidly developing a reputation as an overachiever and ground controllers began giving her extra work. They called it the “Peggy Factor” and she took some kidding for being like Spock from the original “Star Trek” series. She didn’t mind. She enjoyed her work on the International Space Station.

Soyuz TMA-1

Soyuz TMA-1 was the first flight of a new type of Soyuz spacecraft. The interior of the Descent Module had been redesigned to accommodate astronauts that were taller or shorter than average after NASA put pressure on Russia on behalf of astronauts who might not fit into the old design. Other improvements included better instrumentation and avionics. Soyuz TMA-1 launched on October 29 with Cosmonauts Sergei Zalyotin and Yuri Lonchakov and ESA Astronaut Frank de Winne from Belgium on board. The Soyuz docked on Pirs on November 1.

While on the International Space Station, de Winne spent a week conducting an experiment that studied the effect of microgravity on genetics. The cosmonauts also conducted a brief study of proteing crystal growth and materials processing in microgravity. The cosmonauts swapped seats on the two Soyuz spacecraft docked to the station, and then returned home in Soyuz TM-34 on November 9. With instructions from controllers on the ground, the Expedition 5 crew watched the reentry of the Soyuz.

On November 10, the launch of STS-113 was scrubbed. Whitson reminded Houston that they were running out of drinks and received permission to take drinking water from the experiments from Expedition 6. She had already completed all of the experiments scheduled for Expedition 5 and asked permission to begin the science experiments planned for Expedition 6. A report from the National Research Council’s Space Studies Board praised NASA’s microgravity research program but it didn’t help continuing budget issues much. The Russians suggested a halt to Expedition crews until the funding crisis was solved and were quickly shot down. Even if they stopped flying Soyuzes and Progresses, NASA still had the Space Shuttle and could continue to deliver components and supplies. Technical problems caused more delays with launching STS-113 and it finally got off the ground on November 23, 2002 to deliver Expedition 6.

Auroras As Seen On The International Space Station

How cool would it be if you could observe auroras from 250 miles up? Here’s a time-lapse look at what astronauts on the International Space Station see frequently.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=48GOs6x2QKk

International Space Station Collectibles on eBay

[simple-rss feed=”http://rest.ebay.com/epn/v1/find/item.rss?keyword=International+SPace+Station+photographs&categoryId1=1&sortOrder=BestMatch&programid=1&campaignid=5337337555&toolid=10039&listingType1=All&lgeo=1&feedType=rss” limit=5]